Abandoned Appalachia Series – Bledsoe Mining Company

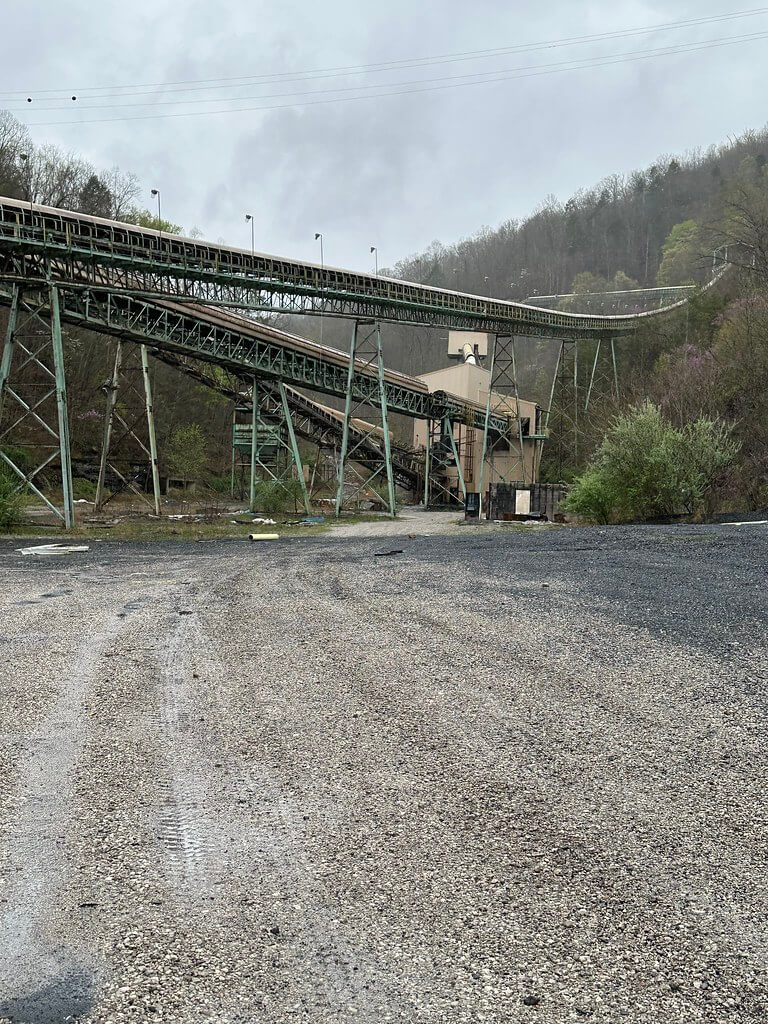

Between Hyden and Harlan, US 421 snakes along Greasy Creek and the headwaters of the Middle Fork. Around Big Laurel the road suddenly opens beside a hulking complex of silos, conveyors, and rusted steel. Locals still call it Bledsoe Mining or the old James River prep plant. Drone footage, roadside photos, and urban exploration videos show empty concrete pads, idle slurry ponds, and conveyor belts frozen against the hills.

On paper, this quiet site was the heart of a sprawling underground complex that stretched under Leslie, Harlan, and Letcher counties. Bledsoe Mining Company, later Bledsoe Coal Corporation, sank multiple mines into Hazard No. 4 and related seams, shipped hundreds of thousands of tons of coal a year, and accumulated a thick paper trail of licenses, petitions, accident reports, and environmental complaints.

Today the Bledsoe complex stands as one of the clearest case studies in late twentieth century Appalachian coal: corporate consolidation, high tonnage underground mining, contested safety, and lingering environmental risk, all mapped onto one mountain valley.

From Bledsoe Mining To A James River Subsidiary

The name “Bledsoe” predates the coal company. A small Harlan County community on the Clover Fork, with a post office active in the early twentieth century, gave the company both a brand and a mailing address.

Bledsoe Coal Corporation itself was incorporated in the 1970s and began opening underground mines in the early 1980s, working Hazard seams near the Leslie–Harlan–Letcher county lines. Geologic maps of the Bledsoe and Helton quadrangles, prepared by the U.S. Geological Survey and Kentucky Geological Survey, show the Hazard No. 4 coal bed cropping out along creeks such as Abner Branch, Peters Branch, and Greasy Creek. These maps help explain why the company concentrated its leases in this narrow belt of coal-bearing rocks.

In June 1995 James River Coal Company purchased Bledsoe and sister producer Leeco Coal Company, folding them into an expanding eastern Kentucky portfolio. The consolidation deepened in 1999 when James River acquired Shamrock Coal Company, which brought in additional underground and surface operations, a preparation plant, and the Clover rail loadout.

By the early 2000s Bledsoe Coal Corporation appeared throughout federal and state filings as a James River subsidiary with its own set of corporate relatives. Bankruptcy schedules and SEC exhibits list “Bledsoe Coal Corporation” and “Bledsoe Coal Leasing Company” among dozens of James River affiliates.

Bledsoe Coal Corporation, Bledsoe Coal Leasing Company, and other James River entities filed Chapter 11 petitions in the Eastern District of Virginia on 7 April 2014, reporting hundreds of millions of dollars in assets and liabilities. After James River’s reorganization, Violation Tracker and lease tables from the Bureau of Land Management show that Bledsoe’s holdings were sold to Revelation Energy at the end of 2014, part of a wave of distressed coal sales in the region. Revelation and its affiliate Blackjewel briefly attempted to restart portions of the complex under new permit names before their own 2019 bankruptcy forced another round of shutdowns.

Mines On Hazard Four

Where the public sees one derelict plant, the paper record shows a cluster of underground mines working several branches of Greasy Creek and its tributaries.

Kentucky’s “Mines Licensed” lists for 2010 and 2011 record Bledsoe Coal Corporation as the operator of mines named BEECHFORK, ABNER BR RIDER, OLDHOUSE BRANCH, TANTROUGH, and related facilities, all using the mailing address “Route 2008, Box 351A, Big Laurel, KY 40808” or a Bledsoe post office box. These state documents tie the company’s Leslie County mines directly to the Big Laurel hub visible from US 421.

Federal production and employment tables from the Energy Information Administration and the Office of Surface Mining list the Beechfork Mine and Abner Branch Rider as active underground operations in the mid 2000s, with the Abner Branch operation alone producing more than half a million short tons in 2007 and employing over one hundred miners.

MSHA investigation reports and accident indices describe the Bledsoe mines as room and pillar operations in the Hazard No. 4 seam and its rider. The Beechfork Mine, located near Helton in Leslie County, worked Hazard No. 4 with continuous miners, mobile bridge haulage, and two advancing production sections, typically running two production shifts and one maintenance shift per day six days a week.

Further up the hollow, Bledsoe Coal Corporation filed petitions for modification of federal safety rules for Mine No. 4 and Mine No. 60, both Leslie County mines on the same coal horizon. A Federal Register notice from December 1999 records Bledsoe’s request to alter how it protected low and medium voltage circuits in those mines, while a later summary of decisions confirms that the petition was granted after MSHA’s investigation.

A separate cultural resource survey, sponsored by the Office of Surface Mining near Greasy Creek in 1996, mapped mine-related features and documented how the expanding Bledsoe underground works overprinted an older Appalachian farm landscape

Taken together, these records show Bledsoe not as a single mine, but as a coordinated complex where multiple portals, shafts, and refuse sites fed a central preparation plant and loadout.

Abner Branch Rider And A 2010 Rib Fall

The most detailed glimpse inside a Bledsoe mine comes from tragedy. On 22 January 2010, continuous miner operator Travis G. Brock, age twenty nine with twelve years of experience, was killed in a rib roll at the Abner Branch Rider Mine.

MSHA’s Report of Investigation describes Abner Branch Rider as an underground mine owned and operated by Bledsoe Coal Corporation, itself a subsidiary of James River Coal Company. The mine worked the Hazard No. 4 rider seam with room and pillar methods and shuttle cars, under a roof control plan that required regular rib support.

On the morning of the accident, Brock was cleaning up a crosscut that had already been bolted when a large rib of coal, more than five feet thick and eight feet long, suddenly broke away. MSHA’s diagrams show the rib striking and pinning him against the machine. The report faults inadequate rib control and notes that prior warning signs, including visible fractures and floor heave, were not properly addressed.

The fatality did not occur in isolation. By 2011 MSHA had issued a notice of “pattern of violations” to Bledsoe’s Abner Branch Rider operation, citing repeated significant and substantial violations under Section 104(e) of the Mine Act. Global Energy Monitor’s summary of Mine 4 and Abner Branch Rider highlights this pattern notice as a turning point in the mine’s regulatory history, while a NIOSH feature on rib falls lists Abner Branch Rider among a string of serious rib fall incidents across the coalfields.

Abner Branch Rider also appears in Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission decisions. In one 2012 order, “Bledsoe Coal Corporation v. Secretary of Labor,” the Commission considers a cluster of contested citations and orders associated with the mine’s MSHA ID 15-19132. Another case, widely cited in later whistleblower reinstatement orders, involves miner Kenneth Wilder and lays out allegations about working conditions and retaliation in and around Abner Branch operations.

These legal documents, combined with MSHA’s technical reports, preserve the voices of inspectors, engineers, and miners as they argued over what safe mining should look like in the tight coal of Leslie County.

Beechfork Mine And Earlier Losses

Seven years before the Abner Branch disaster, another Bledsoe mine suffered a fatal accident. On 6 August 2003 a miner died at the Beechfork Mine, an underground operation “owned and operated by Bledsoe Coal Corporation” near Helton.

MSHA’s fatality investigation explains that Beechfork mined the Hazard No. 4 coal seam using two advancing sections with continuous mining machines and mobile bridge haulage systems. Normal operations ran two production shifts per day, six days a week, with a third shift for maintenance. The report details the mine’s ventilation, haulage entries, and roof control plan, and then reconstructs the events that led to the fatal accident.

State “Mines Licensed” lists reinforce the connection between Beechfork and the roadside plant at Big Laurel. In 2010 and 2011 Beechfork appears under Bledsoe Coal Corporation with the same Route 2008 Box 351A Big Laurel address used for Abner Branch Rider and Oldhouse Branch.

Hearings before Congress on backlogs of contested mine safety cases show Bledsoe’s extensive citation history. A 2010 House hearing includes tables listing dozens of enforcement actions and tens of thousands of dollars in penalties for Abner Branch Rider, Beechfork, Dollar Branch, Tantrough, and other Bledsoe mines during the years immediately surrounding these fatalities.

Through these records the Beechfork Mine emerges as both a crucial production unit and a site of repeated safety scrutiny.

Mapping The Underground

While MSHA reports focus on accidents, Bledsoe’s petitions and the geologic record reveal how engineers imagined the mine complex underground.

In 1999 Bledsoe Coal Corporation petitioned MSHA to modify application of 30 CFR 75.900 at Mine No. 4 and Mine No. 60, both in Leslie County. The Federal Register summary notes that the company wanted to use certain electrical contactors instead of the under voltage circuit breakers prescribed by the rule, arguing that its proposed arrangement would provide equal or greater protection. The associated MSHA findings describe mine portals, shafts, transformer locations, and feeder cables in a way that reads almost like an underground map.

At a broader scale, U.S. Geological Survey quadrangles and Kentucky Geological Survey digital spatial databases provide the surface frame for Bledsoe’s workings. The “Geologic map of the Bledsoe quadrangle, southeastern Kentucky,” first published in 1971 and later digitized as KGS DVGQ 889, plots coal beds, faults, and structure contours across the ridges and hollows where Bledsoe’s mines later developed. Historic and modern topographic maps show Abner Branch, Greasy Creek, Peters Branch, and the road network that carried men and coal between dispersed portals and the central plant.

These technical sources, though intended for engineers and regulators, now help historians reconstruct how the Bledsoe complex expanded over time and how deeply it penetrated the hills around Big Laurel.

Blowouts, Dams, And Water Pollution

Bledsoe’s impact did not end at the mine portal. Water records and environmental enforcement files document the way underground workings and refuse facilities interacted with streams and hollows.

In March 2009 a mine blowout near Chappell in south central Leslie County sent a torrent of mine water into Robin Branch (reported at the time as Robinson Creek), at an estimated flow of around 10,000 gallons per minute. A blog post by Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, quoting state Energy and Environment Cabinet officials and Associated Press coverage, identifies the responsible operation as a Bledsoe Coal Corporation mine. The incident prompted emergency sampling and raised questions about the mine’s long term water management.

Violation Tracker’s entry for Bledsoe Coal Corporation lists a 2009 water pollution violation with a fifteen thousand dollar penalty, issued by Kentucky regulators and tied to the company’s Kentucky operations under James River’s ownership.

Farther down the watershed, the National Inventory of Dams identifies the “Britton Branch Refuse Dam” in Leslie County, NID ID KY83526, as a coal refuse impoundment owned by Bledsoe Coal Corporation. The listing provides structural characteristics, hazard classification, and regulatory agency information, underscoring the scale of waste management infrastructure associated with the Bledsoe mines.

Environmental groups followed Bledsoe’s plans onto public land as well. In late 2012 Kentucky Heartwood challenged a proposed Bledsoe Coal lease on the Redbird District of the Daniel Boone National Forest in Leslie County. The group’s comments, and a 2013 Federal Register notice, explain that the “Bledsoe/Beechfork Mine LBA Tract” would authorize underground mining of roughly 455,080 metric tons of federal coal, to be extracted through existing portals on private land and tied to the Beechfork Mine.

Heartwood’s critique linked Bledsoe’s history of safety and environmental issues, including the Abner Branch pattern of violations, to concerns about subsidence, water quality, and forest ecology on the Redbird District.

Taken together, the blowout, the refuse dam, the lease application, and the enforcement data show how Bledsoe’s mines reshaped not just the inside of the mountain, but also the hydrology and risk profile of Leslie County’s streams.

Contesting Safety And Health

Beyond environmental enforcement, Bledsoe Coal Corporation appears in miners’ health and safety litigation.

Unpublished decisions from the Department of Labor’s Benefits Review Board reference black lung claims against Bledsoe, including the case of Ronnie Eversole, whose earlier claim naming Bledsoe Coal Corporation was denied by the Board in 2000. These files, while careful not to disclose medical details, document how miners and survivors sought compensation for chronic respiratory disease tied to work at Bledsoe and other James River affiliates.

At the same time, Bledsoe contested many MSHA penalties, contributing to the backlog of cases that prompted congressional hearings in 2010. The House record on reducing the backlog includes tables that list Bledsoe Coal Corporation’s outstanding penalties and the number of contested enforcement actions at Abner Branch Rider, Beechfork, Dollar Branch, and other Kentucky mines.

Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission orders, including “Bledsoe Coal Corporation v. Secretary of Labor” and opinions citing “Wilder v. Bledsoe Coal Corp.,” preserve testimony and argument from both miners and management. They show a company operating under constant regulatory pressure and a workforce navigating the narrow space between production demands and safety rules.

Bankruptcy, Sale, And An Abandoned Plant

When James River Coal filed Chapter 11 protection in April 2014, it cited weak coal prices and idled mines in multiple states. Press coverage at the time noted that James River had already idled its Bledsoe operations months earlier in response to market conditions.

Bankruptcy schedules and subsequent litigation make clear that Bledsoe Coal Corporation and Bledsoe Coal Leasing Company were integral parts of the James River group. Case dockets list them as separate debtor entities with their own case numbers and bank accounts, but their fate was tied to James River’s overall restructuring plan and asset sales.

After the sale of Bledsoe’s assets to Revelation Energy, and Revelation’s later connection to Blackjewel, the former Bledsoe complex entered a new and uncertain phase. A Facebook thread in the “Forgotten Coalfields” community, posted by local observers, identifies the roadside plant near Big Laurel as an old James River facility with the Beechfork Mine portals across the road and notes that the property passed through Revelation and Blackjewel before being abandoned again.

By the 2020s visual documentation dominates the public record. Drone photographs on Flickr show the Bledsoe Coal Corporation prep plant at Bledsoe, Kentucky, with its silos, conveyors, and settling ponds slowly weathering in place. Urban exploration videos on YouTube take viewers along the same back roads and into the same overgrown yards that earlier fieldworkers visited, but now the focus is on decay rather than production.

The plant that once processed hundreds of thousands of tons of coal a year is now a landmark in a landscape of abandonment.

Reading Bledsoe In The Landscape

For drivers along US 421, Bledsoe Mining Company is a glimpse out the window: concrete pads, steel, and water against the ridge. The documentary record, however, shows that this corner of Leslie County was one of the most intensely regulated and litigated underground coal complexes in eastern Kentucky during the turn of the twenty first century.

Primary sources tie the Big Laurel site to a network of mines on Hazard No. 4 and its rider, describe daily operations at Abner Branch Rider and Beechfork in fine detail, and capture the moment when a rib fall can change a family forever. Environmental records document blowouts, refuse dams, and the struggle over whether to extend Bledsoe’s workings under national forest land. Corporate and bankruptcy filings trace Bledsoe’s path from independent company to James River subsidiary, then to Revelation and Blackjewel, and finally into the long, uncertain tail of post coal reclamation.

For Appalachian historians, Bledsoe’s value lies in that layered record. In one narrow valley on the Leslie–Harlan line, we can follow the arc of late twentieth century coal: geologic mapping, mechanized underground mining, pattern of violations and fatal accidents, environmental blowouts, federal lease debates, corporate bankruptcy, and the quiet of an abandoned prep plant.

The story of Bledsoe Mining Company is not just a story about one company. It is a case file for how Appalachia’s coal era reshaped land, law, and lives, and how those changes linger long after the last shift leaves the mine yard.

Sources & Further Reading

James River Coal Company, et al. In re James River Coal Company, et al.: Consolidated List of Creditors and Related Filings (Chapter 11, U.S. Bankruptcy Court, Eastern District of Virginia, 2014). Accessed December 26, 2025. https://document.epiq11.com/document/getdocumentbycode/?docId=2512553&projectCode=JR2&source=DM

Kentucky River Coal Corporation and Shamrock Coal Company. Coal Mining Lease Agreement between Kentucky River Coal Corporation and Shamrock Coal Company (June 30, 1982), with subsequent assignment and consent to Bledsoe Coal Leasing Company, Inc., December 14, 1990. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://contracts.justia.com/companies/international-coal-group-inc-33280/contract/809681/

Commonwealth of Kentucky, Secretary of State. Business Records for “Bledsoe Coal Corporation” and “Bledsoe Coal Leasing Company, Inc.” Accessed December 26, 2025. https://web.sos.ky.gov/ftsearch/

Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA). Report of Investigation: Underground Coal Mine, Fatal Fall of Face, Rib, or Pillar – Abner Branch Rider Mine, Bledsoe Coal Corporation, Leslie County, Kentucky, ID No. 15-12941 (Travis G. Brock), January 22, 2010. Arlington, VA: MSHA, 2010. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.msha.gov/sites/default/files/Data_Reports/Fatals/Coal/2010/ftl10c02.pdf

Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA). Report of Investigation: Underground Coal Mine, Fatal Powered Haulage Accident – Beechfork Mine, Bledsoe Coal Corporation, Helton, Leslie County, Kentucky, ID No. 15-18376, June 20, 2003. Arlington, VA: MSHA, 2003. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://arlweb.msha.gov/FATALS/2003/FTL03c17.HTM

Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA). Petition for Modification – Bledsoe Coal Corporation, Mine No. 4 and Mine No. 60, Docket No. M-1999-112-C. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.msha.gov/petition-docket-no-m-1999-112-c

U.S. Department of Labor. “Summary of Decisions Granting in Whole or in Part Petitions for Modification.” Federal Register 64, no. 240 (December 15, 1999): 70054–70055. (Includes petition of Bledsoe Coal Corporation, Docket No. M-1999-112-C.) Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1999-12-15/pdf/99-32494.pdf

Commonwealth of Kentucky, Office of Mine Safety and Licensing. Annual Report 2001. Frankfort: Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet, 2002. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://eec.ky.gov/Natural-Resources/Mining/Mine-Safety/Documents/2001%20Annual%20Report.pdf

Commonwealth of Kentucky, Office of Mine Safety and Licensing. Annual Report 2002. Frankfort: Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet, 2003. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://eec.ky.gov/Natural-Resources/Mining/Mine-Safety/Documents/2002%20Annual%20Report.pdf

Commonwealth of Kentucky, Division of Mine Safety. “Mines Licensed in Kentucky.” Accessed December 26, 2025. https://eec.ky.gov/Natural-Resources/Mining/Mine-Safety/safety-inspections-and-licensing/Pages/licensed-mines-by-year.aspx

Kentuckians For The Commonwealth (KFTC). “Mine Blowout in South Central Leslie County.” March 28, 2009. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://archive.kftc.org/blog/mine-blowout-south-central-leslie-county

Kentucky Heartwood. “Kentucky Heartwood Challenges Bledsoe Coal Lease.” February 6, 2013. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://kyheartwood.org/forest-blog/extraction/kentucky-heartwood-challenges-bledsoe-coal-lease/

Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, U.S. Department of the Interior. “Notice of Availability of the Environmental Assessment and Notice of Public Hearing; Federal Coal Lease by Application, Bledsoe/Beechfork Mine LBA Tract.” Federal Register 78, no. 121 (June 24, 2013). Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2013/06/24/2013-14981/notice-of-availability-of-the-environmental-assessment-and-notice-of-public-hearing-federal-coal and https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2013-06-24/pdf/2013-14990.pdf

Good Jobs First. “Violation Tracker: Bledsoe Coal Corporation – Environmental and Safety Enforcement Records.” In Violation Tracker database. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://violationtracker.goodjobsfirst.org/violation-tracker/ky-bledsoe-coal-corporation-1

“Britton Branch Refuse Dam – KY83526, Leslie County, Kentucky.” National Inventory of Dams entry via Recordnet. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://data.recordnet.com/dam/kentucky/leslie-county/britton-branch-refuse-dam/ky83526/

Duncan, Gary M. Coal Mine Survey Near Greasy Creek in Leslie County, Kentucky. Cultural-resource management report. Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR). Accessed December 26, 2025. https://core.tdar.org/document/420247/coal-mine-survey-near-greasy-creek-in-leslie-county-kentucky

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Ohio River Basin Climate Change Pilot Study – Appendices. 2017. (Includes discussion of high-hazard coal-waste dams such as Britton Branch Refuse Dam, KY83526.) Accessed December 26, 2025. https://nursery-crop-extension.mgcafe.uky.edu/sites/nursery-crop-extension.ca.uky.edu/files/usace_ohio_river_basin_cc_report_may_2017.pdf

U.S. Geological Survey. Helton, Kentucky: 7.5-Minute Series (Topographic) Quadrangle Map. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey, 1974. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://prd-tnm.s3.amazonaws.com/StagedProducts/Maps/HistoricalTopo/PDF/KY/24000/KY_Helton_708869_1974_24000_geo.pdf

Kentucky Geological Survey. “Groundwater Resources of Leslie County, Kentucky.” Online groundwater atlas entry. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.uky.edu/KGS/water/library/gwatlas/Leslie/Geology.htm

Yang, X.Y., and M. Stidham. “Spatial Database of Digitally Vectorized Geologic Quadrangles (DVGQ) for Kentucky.” Kentucky Geological Survey, 2006. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kgs_data/8/

Kala_T. “Bledsoe Coal Corporation: Bledsoe, KY” (photo album). Flickr. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.flickr.com/photos/202678837@N08/albums/72177720329666067

“Morning’s Minion” (Sharon). “‘In the Deep Dark Hills of Eastern Kentucky.’” Morning’s Minion blog, July 11, 2017. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://wwwmorningsminion.blogspot.com/2017/07/in-deep-dark-hills-of-eastern-kentucky.html

andyw513. “Exploring the Abandoned Bledsoe Coal Corporation.” YouTube video, posted 2025. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WAG9lEdW_Bs

Forgotten Coalfields of Appalachia (Facebook group). “Old James River Prep Plant in Leslie County KY.” Group post, ca. 2022. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.facebook.com/groups/forgotten.coalfields/posts/1091602155061262/

JamieRawx. “Bledsoe Coal- Letcher Co. KY.” r/Appalachia (Reddit), May 2023. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.reddit.com/r/Appalachia/comments/137iy6g/bledsoe_coal_letcher_co_ky/

Cheves, John. “Four Citations Issued Against Leslie Mine Where Worker Killed.” Lexington Herald-Leader, November 10, 2015. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.kentucky.com/news/state/kentucky/article44034972.html

Good Jobs First. “Violation Tracker Parent Company Summary: James River Coal Company and Bledsoe Coal Corporation.” In Violation Tracker database. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://violationtracker.goodjobsfirst.org/

Global Energy Monitor. “Bledsoe Coal Mine 4 / Bledsoe Mining Complex.” Global Energy Monitor Wiki, updated April 29, 2021. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.gem.wiki/Bledsoe_Coal_Mine_4

Associated Press. “Two Dead in Kentucky Mine Collapse.” CBS News, April 29, 2010. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/two-dead-in-kentucky-mine-collapse/

Alaska Dispatch News. “Hundreds Died in Kentucky Coal Mines in Decades After Mine Blast Exposed Safety Problems.” Anchorage Daily News, July 8, 2013. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.adn.com/nation-world/article/hundreds-died-kentucky-coal-mines-decades-after-mine-blast-exposed-safety-problems/2013/07/08/

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. “James River Coal Company – Prospectus (Form S-1/A), May 23, 2005.” Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1297720/000114544305001220/d17147.htm

Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet. Kentucky Coal Facts, 12th Edition (2011–2012). Frankfort: Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet, 2012. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://eec.ky.gov/Energy/Coal%20Facts%20%20Annual%20Editions/Kentucky%20Coal%20Facts%20-%2012th%20Edition%20%282011-2012%29.pdf

U.S. Energy Information Administration. “Spot Coal Price Trends Vary across Key Basins During 2013.” Today in Energy, January 2014. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=14631

Reuters. “James River Coal Files for Bankruptcy Protection.” April 7, 2014. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/article/business/james-river-coal-files-for-bankruptcy-protection-idUSBREA361WJ/

Author’s Note: This is one of my favorite places I have visited because so much of the old infrastructure is still standing. If you go, please be careful. Respect posted signs and private property, watch for unstable ground and structures, and avoid entering any tunnels or buildings without permission. Conditions can change fast, so go with a partner, bring proper gear, and leave everything as you found it.