Forgotten Appalachia Series – Hidden Pioneer Cemetery on Clover Street of Harlan County

In the middle of downtown Harlan, traffic rolls past the courthouse, the river slips behind its floodwall, and most people never notice the small, fenced patch of grass tucked behind the NAPA auto parts store on East Clover Street. For decades it was walled in by a Ford dealership building, a blank brick face turned toward the sidewalk. Only after the structure came down in 2022 did the public see what had been there all along: a tiny pioneer graveyard, one of the oldest burial grounds in Harlan County, boxed in by twentieth century commerce and nearly erased from memory.

Today locals know it as the Turner Cemetery, the “secret cemetery,” or the hidden cemetery on Clover Street. Beneath the grass and uneven stones lie members of the families who first claimed this bend of the Cumberland River, long before there was a City of Harlan, a Ford building, or a paved Clover Street at all.

A Family Graveyard at the Edge of a Frontier Town

The story of this yard begins with the families who settled the forks of the Cumberland in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Genealogist William C. Kozee’s classic work on the region lists the Howards, Turners, and Middletons among the earliest settlers on the river in what is now Harlan County, with Hensleys, Napiers, Kellys, Sargents, and others following close behind.

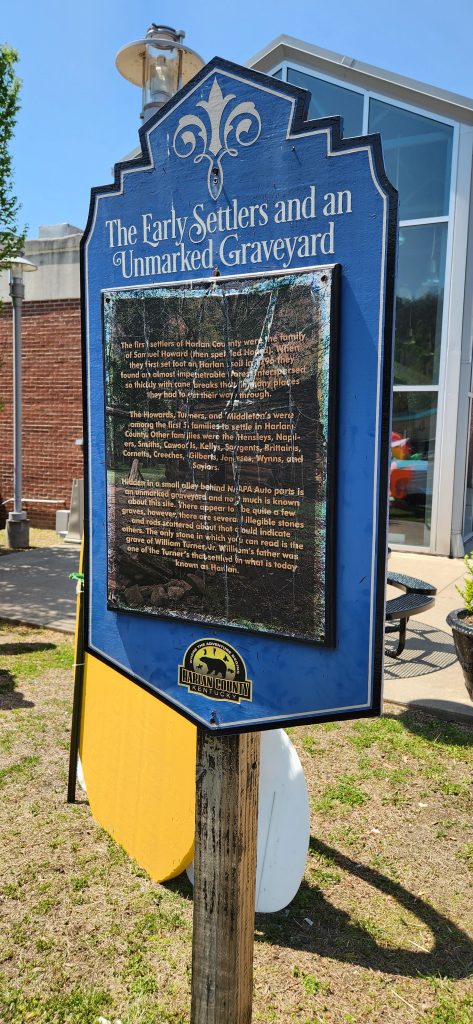

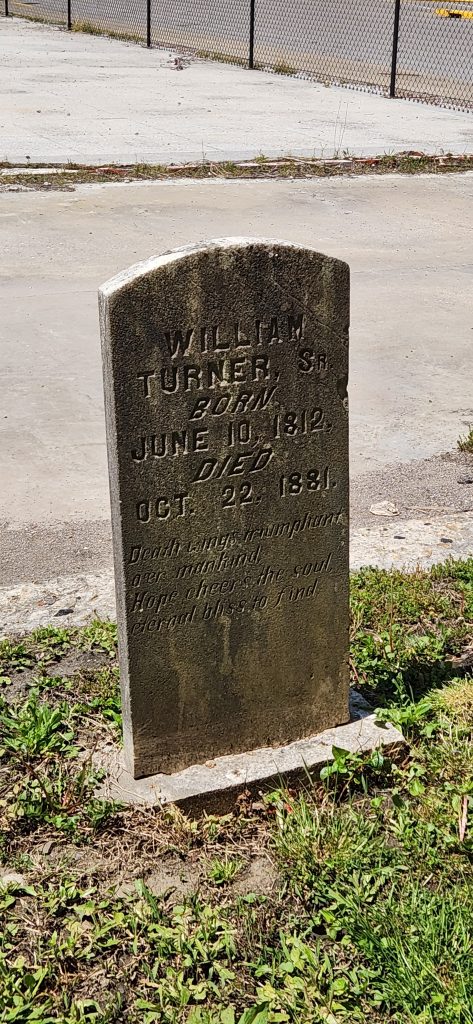

A modern highway marker on East Clover Street, titled “The Early Settlers and an Unmarked Graveyard,” pulls those names into the landscape. It explains that Samuel Howard’s family were the first documented white settlers in Harlan County in the 1790s, and that the Turners and Middletons soon joined them. The marker stands within sight of the little graveyard and notes that only one stone in the plot can still be read: the monument of William Turner, identified on the marker as William Turner Jr.

William Turner’s own memorial on Find A Grave gives him a birth year of 1812 and a death date in 1881, placing him squarely in Harlan County’s first century of organized settlement. The entry confirms that he is buried in the Turner Family Cemetery in downtown Harlan and describes the site as a small plot behind the NAPA store at what was once the Turner homeplace. Local genealogies and family histories describe him as one of the most prominent men in nineteenth century Harlan County, born on Clover Fork and connected by blood or marriage to many later residents of the county.

In the early 1800s, before public cemeteries were common in the mountains, families often set aside a corner of their home tract as a burial ground. Deeds for town lots that later became Clover Street show Turner ownership and, in some cases, language reserving a family graveyard even as the property changed hands. Court records and tax lists reinforce the picture of a Turner homestead that grew into a small cluster of houses at the edge of what would become Harlan’s commercial core. Over time the city grew up around this family yard without ever entirely displacing it.

From Homestead Yard to “Secret Cemetery”

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Turner home stood near the heart of a growing county seat. Harlan’s business district spread along Main Street and up the side streets, including the short stretch that became Clover Street. Sanborn fire insurance maps and early photographs show a mix of wood and brick structures in the block between the courthouse and the river, with rear yards, sheds, and open spaces tucked between them.

As the automobile age arrived, the Turner homestead land shifted from residential to commercial use. Local memories and property records place successive garages and dealerships on the lot, culminating in the Harlan Ford Motor Company building at 206 East Clover Street. When that structure went up, the family graveyard seems to have been left as an open courtyard behind the commercial storefront, surrounded by brick walls and largely hidden from public view.

Find A Grave’s Turner Family Cemetery listing, and later social media discussions among Harlan residents, describe the plot as containing around a dozen visible graves at one time, though only William Turner’s stone remains legible today. Oral histories collected locally recall other markers that have since broken, tipped, or sunk out of sight.

Even as the site disappeared from the everyday landscape, it did not vanish entirely from memory. Harlan County tourism staff, drawing on local historians and family tradition, included a “Hidden Cemetery” in their list of twenty five historic stops. The short description notes that there is a cemetery in downtown Harlan on Clover Street that serves as “the final resting place for members of some of Harlan County’s founding families.” Those founding families were the same Turners, Howards, Middletons, and their kin whose names appear in Kozee’s pioneer roster and in early county histories.

Feud Country And The Turner Name

To understand why this little graveyard holds such power in Harlan’s imagination, it helps to remember that the Turner family stood at the center of one of Kentucky’s best known mountain feuds. Late nineteenth century newspaper reports and later genealogical essays trace a long running conflict between the Turners and the Howards, with killings in and around Harlan town.

Modern summaries of the Turner–Howard feud, along with your own work on the Baker, Howard, and Turner feuds, place the Turner home and yard along the route of several confrontations. Oral tradition in Harlan repeats stories of shootouts on the street that is now Clover, and tales of wounded feudists staggering to the family house. Whether every detail of those stories can be verified through court records and death certificates is almost beside the point. The Turner cemetery on Clover Street has become, in local imagination, the resting place not only of pioneers and civic leaders but of men and women caught in the violence of the feud years.

Death certificates from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries sometimes list “Turner Cemetery” or “Old Harlan Cemetery” as the place of burial for Harlan town residents. Those records, combined with obituary notices in the Harlan Enterprise that specify burial “in the Turner cemetery on Clover Street,” make clear that the yard served more than just the immediate Turner household. Neighbors, kin, and possibly feud casualties were carried through town and laid to rest there, within sight of the courthouse and the river.

Rediscovery During A Demolition

For most of the twentieth century, though, the wider public could not see any of this. The Ford building fronted Clover Street; behind it, the small yard with its stones lay invisible except to those who worked there or knew exactly where to look. Some Turner descendants, a few old timers, and a handful of county officials kept the memory alive, but to most people the idea of a pioneer cemetery in the center of town sounded like a rumor.

That changed in 2022. When the aging auto building passed into county hands and officials moved to demolish it, the brick shell came down and exposed the courtyard behind. Local television station WYMT covered the scene in April of that year, describing the newly visible Turner Cemetery as one of the county’s oldest graveyards, nicknamed the “secret cemetery” because it had been hidden between downtown buildings. Harlan County Judge Executive Dan Mosley told reporters that county leaders had known of the graves for years and believed that several of the original pioneers of Harlan County rested there. He emphasized that the county’s plan was to preserve the cemetery, not disturb it, and to add historically appropriate fencing and signage to explain who is buried there and why it matters.

In the same story, local historian Dr. James Greene pointed to the single clearly readable headstone for William Turner and noted that many people in Harlan today are descended from the man in that grave. The WYMT coverage, shared widely on social media and picked up by regional outlets, effectively reintroduced the Turner cemetery to the public as a heritage site rather than an inconvenient leftover in a redevelopment project.

Tourism promoters seized on the moment. Visit Harlan County’s social media channels highlighted the hidden cemetery as part of a bicentennial campaign, inviting residents to see if they could find the graves of some of the county’s first settlers tucked away in downtown. In haunted history tours and fall event guides, the graveyard now appears alongside mass graves, coal camp cemeteries, and other liminal spaces where memory, loss, and curiosity all crowd together.

Reading The Stone And The Paper Trail

On the ground, the most obvious evidence for the history of the site is the stone of William Turner. Its inscription fixes his death to the early 1880s and ties his life to the Turner line that helped build Harlan’s civic and economic institutions in the late nineteenth century. That stone, however, is only part of the story.

Historic marker text, compiled using county records and family histories, points back to Samuel Howard as the first permanent settler at Harlan and situates the Turners and Middletons as part of the next wave of families on the river. The marker’s placement in front of or near the graveyard quietly asserts that this small burial ground is where those early lines converge in the soil.

Cemetery registries and online gazetteers add another layer of evidence. Federal Geographic Names Information System based tools such as RoadsideThoughts and genealogical aggregators list multiple Turner cemeteries scattered across Harlan County, sometimes noting alternative names such as Middleton Turner Cemetery or Turner Creek Cemetery. The downtown Turner Family Cemetery entry on Find A Grave makes a point of warning readers not to confuse this tiny urban plot with those larger rural burial grounds, underscoring how unusual it is for a pioneer family cemetery to survive in the middle of a later county seat.

Beyond grave listings, a rich paper trail waits in local archives. Harlan County deed books and plats reveal the legal history of the Clover Street lots, from Turner homestead tracts to later commercial parcels. In some mountain counties it is common to see language that carves out “the family graveyard” or reserves it from sale; a careful reading of Harlan’s deeds for this block can show how the cemetery was handled when the Ford property changed hands. City council minutes and fiscal court records may mention the cemetery when the streets were named, when utility lines were laid, or when demolition of the building was discussed.

Sanborn fire insurance maps, which charted downtown Harlan across several decades, help reconstruct how the graveyard was boxed in and when structures shifted around it. Any blank courtyard shape behind a labeled commercial building on the Clover Street block is worth a close look.

Vital records and old newspaper issues anchor the cemetery to individual lives. Kentucky death certificates housed by the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives occasionally record “Turner Cemetery” or “Old Harlan Cemetery” as the burial place for nineteenth century residents whose families remained close to the downtown area. Obituaries in the Harlan Enterprise and other regional papers sometimes add detail, specifying a funeral at a downtown church and burial in the Turner cemetery behind what later became the Ford building.

Oral history projects housed at the Harlan County Public Library, Southeast Kentucky Community and Technical College, and in collections inspired by Alessandro Portelli’s work in They Say in Harlan County preserve community stories about the cemetery. In interviews collected for broader projects on coal, class conflict, and memory, narrators occasionally digress to talk about a “little graveyard back of the old Ford place” or “Turner Cemetery downtown,” providing first person testimony that the site remained part of Harlan’s mental map even when it was physically invisible.

Coal, Cleanup, And Brownfield Ground

By the time the Turner cemetery reemerged into public view, the land around it had lived several lives of its own. The rise of the coal economy in the early twentieth century turned Harlan from an isolated mountain courthouse town into an industrial center, bringing banks, garages, and dealerships to what had been a frontier edge. Elmon Middleton’s 1930s history of Harlan County describes how corporations like Fordson Coal and Ford Motor invested in the region, how the L and N Railroad pushed into the county, and how Harlan’s once backwoods streets filled with new concrete and brick buildings.

Those developments left environmental traces. Federal environmental databases today list the former Harlan Ford Motor Company site at 206 East Clover Street as a brownfield cleanup location, documenting petroleum contamination and redevelopment planning. That record confirms the modern street address and land use history for the parcel that overlays the cemetery and helps explain why demolition and remediation finally brought the old stones back into the open.

In a sense, the Turner cemetery is now surrounded by three eras at once. The graves belong to the early settler and feud period, the old Ford building and its concrete floor mark the coal boom and automobile age, and the brownfield record belongs to the present era of cleanup, heritage tourism, and renewed interest in downtown redevelopment.

Preserving A Tiny But Weighty Landscape

Since the Ford building came down, Harlan County officials and local advocates have treated the Turner cemetery as both a responsibility and an opportunity. In interviews and public statements, Judge Executive Mosley has stressed that the county will not relocate the graves. Instead, proposals include erecting historically sympathetic fencing, installing interpretive signage, and possibly integrating the site into walking tours that explore the town’s early history and feud geography.

Advocates in cemetery and genealogy groups have launched small documentation projects, photographing stones, mapping the yard, and sharing information on social media under titles such as “Turner Cemetery in Harlan, Kentucky: History and Preservation.” Tourism outlets have begun to include the cemetery in lists of “hidden” or “forgotten” sites in the county, linking it thematically to other overlooked graveyards, influenza mass graves near Lynch, and remote hillside plots that once belonged to coal camps and farmsteads.

The next steps will likely depend on how far local researchers want to push the archival and archaeological work. Ground penetrating radar surveys could help estimate the number of burials in the yard, going beyond the dozen or so visible headstones mentioned by Dr. Greene. Systematic surveys of death certificates, deeds, Sanborn maps, and early photographs could produce a more definitive roster of people who may lie there. Any such work would need to be done with care, in consultation with descendant families and local churches, to honor the site’s status as an active burial ground, not a relic to be mined for data.

Why This One Small Cemetery Matters

In a county dotted with mountain graveyards, the Turner cemetery on Clover Street might seem small. It is, physically, just a courtyard sized plot between downtown buildings. Yet it carries an outsized weight in the story of Harlan.

This yard, more than two centuries old, links the first permanent white settlers on the Cumberland to the later coal and feud era. It reminds us that Harlan was once a cluster of family homes on a river bend, long before it was a boom town. It makes visible how easily a family graveyard can be walled in by later development, hidden but never quite erased. It also shows how primary sources of all kinds stone inscriptions, deeds, fire maps, brownfield files, death certificates, oral histories, tourism blurbs, and television news reports can be woven together to bring a forgotten landscape back into focus.

Standing at the fence line today, looking over William Turner’s lone legible stone and the soft humps that mark other graves, you can see more than just weathered marble. You see the outline of the first cabins along the river. You see a town taking shape and then crowding around its dead. You see the Ford building rising and falling, and a community deciding, at last, that the little yard behind it matters enough to keep.

For Harlan County, the hidden pioneer cemetery on Clover Street is not just a curiosity behind a parts store. It is a compact, living archive of the county’s beginnings, its conflicts, and its changing relationship with its own past, preserved in a patch of grass right in the heart of town.

Sources & Further Reading

The Historical Marker Database. “The Early Settlers and an Unmarked Graveyard.” Historical marker 181323, Harlan, Kentucky. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=181323.

“Old Harlan Cemetery.” Business listing, Chamber of Commerce, Harlan, Kentucky. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.chamberofcommerce.com/business-directory/kentucky/harlan/cemetery/2030319693-old-harlan-cemetery.

“Turner Family Cemetery in Harlan, Kentucky.” Find a Grave. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2420501/turner-family-cemetery.

“Turner Cemetery in Kitts, Kentucky.” Find a Grave. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2598078/turner-cemetery.

“Harm Turner Cemetery in Big Laurel, Kentucky.” Find a Grave. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2668427/harm-turner-cemetery.

“Harlan County KY Cemetery Records.” LDSGenealogy. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://ldsgenealogy.com/KY/Harlan-County-Cemetery-Records.htm.

“Information on the Old Harlan City Cemetery.” Facebook post in “Harlan County Kentucky” history group. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.facebook.com/groups/789010344491250/posts/2484681091590825/.

Wikitree contributors. “William Turner III (1812–1881).” Wikitree. Last modified March 24, 2025. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Turner-27855.

Middleton, Elmon. Harlan County, Kentucky. Big Laurel, VA: n.p., 1934. PDF, Seeking My Roots. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.seekingmyroots.com/members/files/H002174.pdf.

Kozee, William C. Pioneer Families of Eastern and Southeastern Kentucky. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1957. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.amazon.com/Pioneer-Families-Eastern-Southeastern-Kentucky/dp/0806305762.

Kentucky Department for Public Health. Kentucky Death Records, 1911–1965. Digital images and index, FamilySearch. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/1223617.

Sirles, Ethan, and Chas Jenkins. “19th Century ‘Secret Cemetery’ Uncovered in Harlan County.” WYMT Mountain News, April 4, 2022. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.wymt.com/2022/04/04/19th-century-secret-cemetery-uncovered-harlan-county/.

“End of the Old Ford Building, the Location of Harlan’s ‘Secret Cemetery’ (and a Love Story).” YouTube video, 13:26, 2022. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JPtd7qPnKx4.

“One of the Buildings by the Cemetery Is the Old Harlan Ford Motor Building.” Facebook post, WYMT News page, April 4, 2022. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.facebook.com/WYMTNews/posts/one-of-the-buildings-by-the-cemetery-is-the-old-harlan-ford-motor-building/10159585588859584/.

“19th Century ‘Secret Cemetery’ Uncovered in Harlan County.” Facebook post, Kentucky Cemeteries group, April 4, 2022. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.facebook.com/groups/kentuckycemeteries/posts/1413551719386159/.

“25 Historic Stops in Harlan County.” Harlan County Trails, September 8, 2021. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.harlancountytrails.com/blog/25-historic-stops-in-harlan-county/.

“Haunted Harlan County Tour.” Harlan County Trails. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.harlancountytrails.com.

“223 Things to Do in Harlan County in 2023.” Harlan County Trails blog, 2023. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.harlancountytrails.com/blog/223-things-to-do-in-harlan-county-in-2023/.

“Turner and Howard Families of Harlan County and the Feud between the Two.” Kentucky Kindred Genealogy, October 6, 2023. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://kentuckykindredgenealogy.com/2023/10/06/turner-and-howard-families-of-harlan-county-and-the-feud-between-the-two/.

“The Howards and the Turners: A Harlan County Feud.” YouTube video, Appalachian Legends, 2020. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMa8Ig4FBBw.

“The Howards Who Had Cousins in Clay Co. Ky. Had a Feud of Their Own in Harlan Co.” Facebook post in “Appalachian Americans” group. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.facebook.com/groups/AppalachianAmericans/posts/10161361661178648/.

Portelli, Alessandro. They Say in Harlan County: An Oral History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.amazon.com/They-Say-Harlan-County-History/dp/0199934851/.

Turner, William H. The Harlan Renaissance: Stories of Black Life in Appalachian Coal Towns. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2021. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://discover.bklynlibrary.org/item?b=12515933.

“Mine Deaths from the Harlan Miners Memorial Monument.” USGenWeb Harlan County, Kentucky. PDF. Accessed December 26, 2025. https://www.usgenwebsites.org/KYHarlan/Mine%20Deaths%20From%20The%20Harlan%20Miners%20Memorial%20%20Monument.pdf.

Author’s Note: I still think it is a little insane that this cemetery sat hidden for so long right beside the courthouse, with generations walking past it and never knowing it was there. Now that the building is gone and the graves are visible again, it feels like a piece of Harlan County’s foundation has finally stepped back into view. This is rich, powerful history, and it is a good thing for Harlan County that it can now be seen, understood, and cared for in the heart of town.