Appalachian History Series – The Battle of Evarts: Harlan County’s First Shot in the Coal Wars

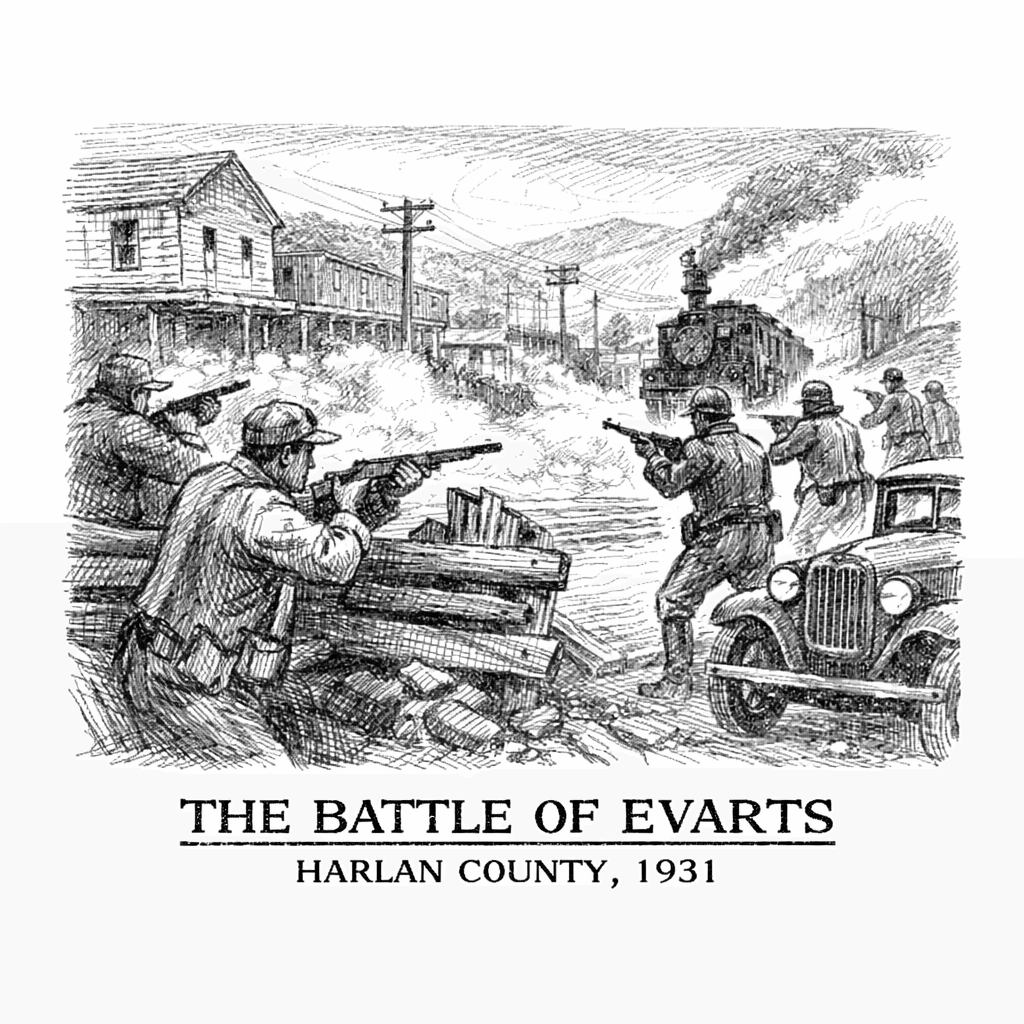

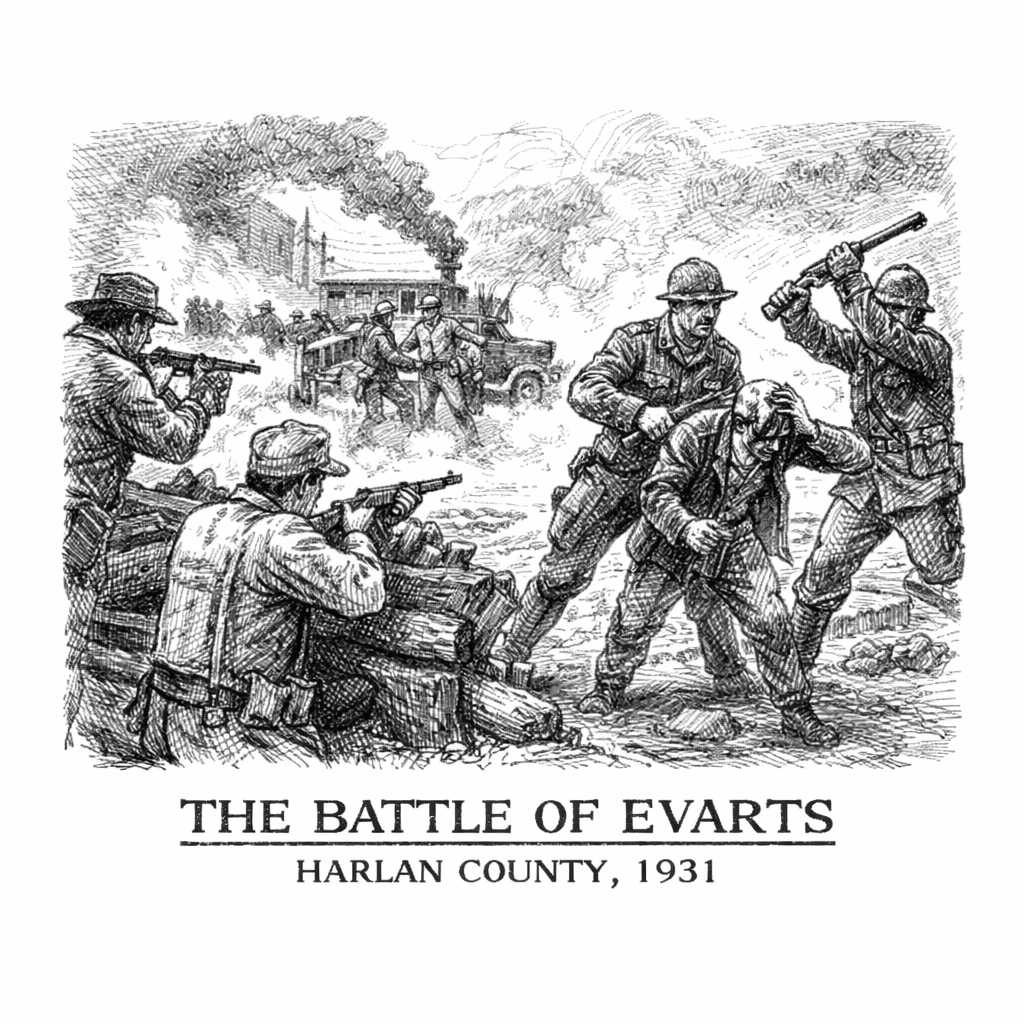

On a gray May morning in 1931, people along the Poor Fork road woke to the crack of rifle fire echoing off Pine Mountain. By the time the shooting stopped near the town of Evarts, three mine deputies and one coal miner lay dead. In less than half an hour, a small-road skirmish in Harlan County became front page news across the United States and gave the nation one of its most enduring phrases for coalfield conflict: Bloody Harlan.

This article follows that morning from the ground up. It leans first on the record left by 1930s reporters, trial transcripts, pamphleteers, and the people who were there, then on later historians who spent decades trying to sort fact from legend.

Evarts Before the Shooting

In early 1931 Harlan County was already a tinderbox. Coal prices had sagged in the late 1920s, and operators responded with wage cuts and speedups underground. On February 16, 1931, the Harlan County Coal Operators’ Association ordered a ten percent wage cut. The United Mine Workers of America saw an opening and moved in to organize a county still dominated by company towns and company stores.

In most of Harlan County, coal companies owned not just the mines but the houses, stores, and streets. Evarts was one of the few incorporated towns that was not a company property. When miners who showed union leanings were fired and evicted from their camp houses, many of them drifted toward Evarts. They pitched tents, rented whatever rooms they could find, and began to turn the town into an organizing hub. Harlan Miners Speak, a 1932 investigative report compiled for the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners, described whole families living in shacks and tents around the county, depending on relief kitchens and union funds for survival.

In March and April the strike at Black Mountain and other mines spread. Company guards were deputized by the county sheriff and used their new powers on and off company property. Strikers reported beatings, evictions, and raids on meetings. Employers saw dynamited mine entries, ambushes of nonunion workers, and a county sheriff’s office overwhelmed by what they framed as a breakdown of law and order. Hevener’s later history of the Harlan County coal miners estimates that at the peak of the first strike around 5,800 miners were idle and only about 900 were still working, a staggering disruption in a single Appalachian county.

Roads like the one that curved past Evarts became front lines. Picketers lined the approaches into town. Miners who had lost their homes carried rifles or shotguns as a matter of course. Company deputies, guards, and private detectives did the same. On both sides, the language of war crept into everyday talk.

May 5, 1931 – The Road Above the River

Most accounts agree on the broad outline of what happened on the morning of May 5, 1931, even when they disagree on the details. Shortly after dawn, a truck belonging to the Black Mountain mine passed through Evarts. Different witnesses later said it was going to collect a foreman, retrieve a new nonunion worker’s belongings, or pick up replacement labor in town. Whatever its purpose, the truck’s appearance angered strikers who were trying to keep any company traffic from moving freely through the valley.

Word went up the line. Pickets began gathering along the highway that hugged the Poor Fork of the Cumberland River just east of town. On the company side, Black Mountain managers sent a three car caravan of armed men to meet the truck and escort it back to the camp. The cars carried a mix of deputies and mine guards, men who lived in an overlapping world of public law enforcement and private security.

Just outside Evarts, the road curved with the river. A hillside rose on one side, bottomland and water lay on the other. When the caravan rounded the bend it encountered armed miners along the roadside and on the slope above the highway. At that point testimonies diverge.

Mine operators and their allies would later describe the encounter as a deliberate ambush laid by a hidden band of strikers. Some strikers and their supporters insisted that the men along the road were a picket line that had been there for days, and that the guards provoked the shooting by attacking a Black miner or driving into the crowd. The later oral testimony of Jim Garland, a Harlan and Bell County miner and songwriter, remembered the confrontation beginning when guards attacked a picket and the rest of the line rushed to his defense. Hevener, drawing on a 1932 United States Senate hearing, called the event an ambush while still acknowledging the conflicting stories in circulation.

What is clear is that a single shot was followed by a storm of fire. For roughly half an hour miners and deputies traded rifle and shotgun blasts along the curve of the road. Some men scrambled behind cars. Others dug into the hillside or lay flat in weeds and ditchbanks. A contemporary magazine piece later summarized the geography in almost cinematic fashion, describing the caravan entering a bend with hill on one side and river bottom on the other just before the shooting started.

When it ended, three deputies were dead: L. D. Lewis, Jim Daniels, and Charles Lankford. A miner, Bennett Hargis, also lay dead from wounds. Several other men on both sides were injured. One guard truck was riddled with bullets. The road itself was left littered with spent shells and broken glass.

The Nation Takes Notice

Within a day, the Battle of Evarts was national news. The New York Times placed the story on its front page on May 6 under the headline “Three Deputies Slain in Kentucky Mine Riot.” The wire copy recounted a firefight between armed miners and coal company guards on the road outside Evarts and reported that state officials were considering sending in troops. The Chicago Daily Tribune ran a front page story the same day, “4 Guarding Mines Slain in Outbreak,” accompanied by a photograph on the back page.

Both papers, like many others across the country, relied heavily on Associated Press and United Press dispatches. Those wire stories framed Evarts as the latest flareup in a violent Appalachian mine war. One widely reprinted description from the period, preserved in later histories, depicts National Guard troops arriving in a “strife torn Evarts coal mining community” and being cheered by nervous residents.

On May 7 the Times followed up with a story titled “Blasts in Mine Zone Alarm Kentuckians,” reporting dynamite explosions in the days after the battle and invoking what one later historian called “reign of terror” language to describe the climate in Harlan County.

The headlines accomplished two things at once. They turned the Poor Fork road into a national symbol of labor violence. They also caught the attention of radical and civil liberties organizations who saw in Evarts a test case for the rights of workers to organize.

Troops, Trials, and Defense Committees

Governor Flem D. Sampson ordered several hundred National Guard soldiers into Evarts two days after the battle. The miners hoped the Guard would serve as a neutral force between them and private gunmen. Instead, guardsmen focused on disarming strikers and restoring production at the mines. Picket lines were broken, meetings were dispersed, and the strike began to lose momentum.

County officials moved quickly to make examples of strike leaders. Dozens of miners were arrested and charged with offenses ranging from carrying concealed weapons to murder and conspiracy. Ultimately eight miners were convicted of conspiracy to murder and received life sentences for their alleged role in the Battle of Evarts. Their convictions became the centerpiece of a national defense campaign.

The Kentucky Miners Defense Committee, formed to support the prisoners and their families, created a paper trail that is one of the richest primary sources for the aftermath of Evarts. Its records, now housed in Kentucky archives and described in finding aids and RootsWeb summaries, include trial transcripts, legal briefs, press releases, and photographs.

Fundraising pamphlets such as Bloody Harlan: The Story of Four Miners Serving Life for Daring to Organize a Union and Facts from the Court Records in the Harlan Frame Up Trials presented the Evarts defendants as victims of a rigged legal system. They reprinted excerpts from courtroom testimony, summarized indictments and jury instructions, and printed portraits of the life sentence prisoners. These pamphlets were openly partisan, but they were built on contemporary court records and remain invaluable for reconstructing what prosecutors argued and how defense attorneys responded.

Civil liberties and left wing organizations added their own investigations. The American Civil Liberties Union pamphlet The Kentucky Miners Struggle offered a summary of Harlan events with particular emphasis on free speech, assembly, and the use of deputies to harass union supporters. Communist aligned groups produced works such as Harry Gannes’ Kentucky Miners Fight, which gave a detailed narrative of the Evarts strike and portrayed the battle as workers defending themselves against “gun thugs” and company terror.

Most famously, a committee that included novelist Theodore Dreiser traveled to Harlan County to take testimony from miners, preachers, and local leaders. Their findings were published in 1932 as Harlan Miners Speak: Report on Terrorism in the Kentucky Coal Fields. The report reproduced testimony from miners about evictions, raids, beatings, and the Evarts battle, alongside statements from Sheriff J. H. Blair and other officials. Later scholars have noted the report’s polemical tone, but they also recognize it as one of the most detailed contemporary records of what Harlan miners said about their own lives.

Songs, Stories, and the Question of Memory

The Battle of Evarts did not have to wait long to enter song and story. In 1931, Florence Reece, the wife of Harlan County union organizer Sam Reece, wrote the song “Which Side Are You On?” while her husband was in hiding from armed men searching their home. The song distilled the experience of the Harlan County War into a stark question about loyalty and courage. Although it did not mention Evarts by name, later scholarship has made clear that the terror described in the song grew from the same months of shooting, evictions, and raids that climaxed on the road near Evarts.

Other cultural responses were more directly tied to the battle. Jim Garland, who later published his oral memoir Welcome the Traveler Home, became one of the key storytellers about Evarts. In interviews recorded decades after the fact, he described the morning of May 5 in vivid detail, including his memory of a Black picket being attacked and the picket line returning fire. His account, cited in the Battle of Evarts entry and later histories, reinforces how central race, class, and memory were to the way the battle was remembered.

By the late twentieth century, oral historians such as Alessandro Portelli began to treat Evarts not only as an event but as a case study in how communities remember violence. Portelli’s They Say in Harlan County compares recorded memories of Evarts and other battles with contemporaneous documents, emphasizing that discrepancies are themselves historically meaningful. Chapter nine, “No Neutrals There,” echoes a phrase that recurs in both song and oral testimony: that in Harlan County in 1931, neutrality was impossible.

Oral history collections at the University of Kentucky’s Nunn Center and the Kentucky Oral History Commission broaden the chorus of voices. Interviews with miners like Orville Sargent, recorded in the 1980s, recount both everyday life underground and the fear and excitement surrounding the Battle of Evarts. Later projects conducted for films such as Harlan County, USA captured older miners and family members recalling the 1930s conflicts while fighting new battles in the 1970s.

On the popular history side, essays such as Bill Bishop’s “1931: The Battle of Evarts” for Southern Exposure, Ron Soodalter’s two part “The Price of Coal” in Kentucky Monthly, and public history pieces like the Clio entry and Patrick Hyde’s “No Neutrals” have distilled the story for new generations. They usually emphasize the short, intense exchange of fire, the four dead men on the gravel road, and the way the battle brought national attention to a conflict the coal companies hoped to keep local.

What the Battle Meant

In the immediate sense, the Battle of Evarts was a defeat for the 1931 strike. Within weeks of the gunfight, the National Guard had broken up picket lines, union organizers were in jail or driven from the county, and most miners had been forced back to work without any concessions from the operators. United Mine Workers membership in Harlan County plummeted.

In a broader historical sense, however, Evarts became impossible to ignore. The four deaths on the Poor Fork road pushed Harlan County into national debates about labor rights, civil liberties, and corporate power. They prompted investigative trips by writers and activists who left behind piles of testimony, photographs, and pamphlets. They helped to shape a national image of Appalachia as a place of both poverty and resistance.

For the people who lived through it, Evarts also marked a line in their own lives. Many who spoke to oral historians later in the century dated marriages, funerals, migrations out of the mountains, and religious conversions from “before the shooting” or “after the battle.”

The battle’s legacy continued to ripple through other struggles, from the 1930s organizing drives that finally brought the United Mine Workers into much of eastern Kentucky to the 1970s Brookside strike captured on film in Harlan County, USA. Generations of activists have sung “Which Side Are You On?” in contexts far removed from Harlan County. The question, however, began in the same world that produced a short, deadly firefight near Evarts in 1931.

Sources & Further Reading

Bishop, Bill. “1931: The Battle of Evarts.” Southern Exposure 4, nos. 1–2 (June 1, 1976): 92–101. Institute for Southern Studies. https://www.facingsouth.org Wikipedia

Hevener, John W. Which Side Are You On? The Harlan County Coal Miners, 1931–39. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978; repr. 2002. https://www.worldcat.org Wikipedia

Taylor, Paul F. Bloody Harlan: The United Mine Workers of America in Harlan County, Kentucky, 1931–1941. Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1990. https://www.worldcat.org Reddit

Portelli, Alessandro. They Say in Harlan County: An Oral History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. https://global.oup.com Clio+1

Ardery, Julia S., ed. Welcome the Traveler Home: Jim Garland’s Story of the Kentucky Mountains. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1983. https://www.kentuckypress.com Wikipedia

National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners. Harlan Miners Speak: Report on Terrorism in the Kentucky Coal Fields. New York, 1932. Reprint with introduction by John Hennen, University Press of Kentucky, 2008. https://appalachiancenter.as.uky.edu/sites/default/files/Harlan%20Miners%20Speak%20-%20Hennen%20Intro.pdfAppalachian Center

American Civil Liberties Union. The Kentucky Miners’ Struggle: The Record of a Year of Lawless Violence in Harlan County. New York: ACLU, 1932. https://www.aclu.org HathiTrust+1

Gannes, Harry. Kentucky Miners Fight. New York: Workers International Relief, 1932. https://www.worldcat.orgInternet Archive+1

Kentucky Miners Defense. Facts from the Court Records in the Harlan Frame-Up Trials. New York: Kentucky Miners Defense, ca. 1937. https://www.worldcat.org Finding Aids at NYU+1

Kentucky Miners Defense Records, 1931–1936. Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University. https://wp.nyu.edu/specialcollections Web Publishing+1

Searcy, Rachel Aileen. “Hell in Harlan.” The Back Table (Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University), May 7, 2013. https://wp.nyu.edu/specialcollections/2013/05/07/hell-in-harlan/ Web Publishing

Amburgey, Bayley Hope. “The Politics of Unionization: The Impact of Politics on the Strength of Kentucky Coal Miners’ Unions.” Senior honors thesis, University of Louisville, 2020. https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors/210/ir.library.louisville.edu

Duff, Betty Parker. “Class and Gender Roles in the Company Towns of Millinocket and East Millinocket, Maine, and Benham and Lynch, Kentucky, 1901–2004: A Comparative History.” PhD diss., University of Maine, 2004. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/183/ Digital Commons at UMaine

Reece, Florence. “‘Which Side Are You On?’ (1931).” In protest-song teaching guide, University of Pittsburgh Voices Across Time. https://voices.pitt.edu/TeachersGuide/Unit7/WhichSideAreYouOn.htm Voices Across Time

“‘Which Side Are You On?’: How Florence Reece Gave American Workers an Anthem.” Mental Floss, May 24, 2023. https://www.mentalfloss.com/entertainment/music/which-side-are-you-on-florence-reece-protest-song Mental Floss

“The Battle of Evarts, Kentucky, 1931.” Clio: Your Guide to History, March 9, 2015. https://theclio.com/entry/12137Clio

Soodalter, Ron. “The Price of Coal, Part I: Bloody Harlan and the Coal War of the 1930s.” Kentucky Monthly, September 30, 2016. https://www.kentuckymonthly.com kentuckymonthly.com

Soodalter, Ron. “The Price of Coal, Part II.” Kentucky Monthly, October 31, 2016. https://www.kentuckymonthly.com/culture/history/the-price-of-coal_1/ kentuckymonthly.com+1

Bishop, Bill. “1931: The Battle of Evarts.” Facing South / Southern Exposure, June 1, 1976. https://www.facingsouth.org Wikipedia

“Battle of Evarts.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Evarts Wikipedia

“Harlan County War.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harlan_County_WarWikipedia

“Remembering Bloody Harlan County.” Parallel Narratives (blog), March 13, 2011. https://parallelnarratives.com/2011/03/13/remembering-bloody-harlan-county/ Parallel Narratives+1

Hyde, Patrick. “No Neutrals: The Harlan County Miner’s Strike of 1931.” PatrickHyde.com, n.d. https://patrickhyde.com/non-fiction/no-neutrals-the-1931-miners-strike-in-harlan-county-kentucky/ Patrick Hyde

Pine Mountain Settlement School. “Bibliography: Harlan County, Kentucky.” Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. https://pinemountainsettlement.net Pine Mountain Collections

New York Times. “Three Deputies Slain in Kentucky Mine Riot.” The New York Times, May 6, 1931. Accessible via ProQuest Historical Newspapers. https://www.proquest.com

New York Times. “Blasts in Mine Zone Alarm Kentuckians.” The New York Times, May 7, 1931. Accessible via ProQuest Historical Newspapers. https://www.proquest.com

Chicago Daily Tribune. “Four Guarding Mines Slain in Outbreak.” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 6, 1931. Also reproduced via RareNewspapers.com. https://www.rarenewspapers.com rarenewspapers.com

Author Note: I grew up in this valley, in a coal camp just down the road from Evarts. All through my childhood I heard people talk about the Battle of Evarts, sometimes in hushed tones, sometimes with a kind of rough pride. Writing this piece is my way of honoring the stories I grew up on and setting them alongside the historical record that shaped our town long before I was born.