Abandoned Appalachia Series – Neely Elementary School of Knott County

A stone schoolhouse above a future lake

If you drive up Yellow Creek toward Building Mountain today, you can still spot it. Before the road tips over the ridge, a stone building sits on the flat ground across from where Roosevelt Honeycutt once kept a store.

Locals remember that building as Neely or Neely Elementary School, one of three small public schools that served the Carr Fork valley before the United States Army Corps of Engineers turned the creek into Carr Creek Lake in the 1970s.

For former student and later teacher Golden Glen Hale, childhood in this corner of Knott County was “filled with games and education” at Neely Elementary, followed by years of watching that same community brace for the coming dam. His oral history for the Carr Creek Oral History Project describes a tight knit neighborhood where school, church, and creek bottom were never far apart and where he later helped turn the closed school into a community space.

Neely’s story is a familiar Appalachian one. It links rural schooling, New Deal and postwar flood control, and the long afterlife of buildings that stubbornly remain when the people they served have been scattered.

A rural school on Yellow Creek

Exactly when Neely Elementary opened is still a matter for the archivists, but surviving records and memories push its operating years at least back to the mid 1940s. The obituary of Lula Venters Mullins, a Knott County native who later spent her career in Clark County, notes that her first teaching position came at “Neely Elementary School” in Knott County in 1944 and recalls that children there pronounced her name as something close to “Loulee.”

By the time Hale started school there in the 1950s, Neely was part of a patchwork of small Knott County schools that also included Carr Creek Elementary and Yellow Creek School. Oral histories from the Carr Creek project describe children walking or riding short bus routes from creekside farms and coal camps to those three schools, with students shifting between them as families moved up and down the valley in search of work.

The school took its name from a local family and place name that appears in county records with several spellings. In his survey of Knott County post offices, place name scholar Robert Rennick notes that the Nealy family also spelled its name Neely, a hint at the tangle of Neelys, Nealys, branches, and post offices that mark maps of the Forks of Troublesome and its tributaries.

Physically, Neely was a stone building set on bottom land above Yellow Creek. In his 2023 interview, Joe Hall III situates the school in a line of landmarks: Yellow Creek School, Neely, the old Carr Creek road, and the businesses and houses that once stood along Kentucky Route 160 and the old 160 road before construction crews began clearing the future lake bed.

Teachers, children, and everyday life

Neely may have been small, but it produced a remarkable paper trail of remembered lives.

Lula Mullins’ early years there fit a larger pattern in Kentucky. In the 1940s county boards of education increasingly relied on local women with limited training to staff scattered one and two room schools. Settlement school leaders at nearby Hindman Settlement School had pushed for better teacher preparation and closer cooperation between county and private institutions for decades, trying to transform rural schooling from rote recitation into something more holistic.

Hale’s memories add texture to that policy history. In the NOAA Voices abstract of his oral history, Neely appears not as a bureaucratic unit but as a place where a boy who sometimes relied on welfare and commodity cheese could still find games on the playground and teachers who encouraged his curiosity. He recalls selling newspapers, learning local history, and eventually returning to the community as a teacher himself.

A home video posted to YouTube by a local family calls the building “Old Neely School” and mentions that the filmer’s mother attended there in the 1960s. The camera pans across the surviving stone walls and windows, confirming what the oral histories suggest. Neely was still open into the 1960s, probably as a small elementary school feeding into Carr Creek High School and later the consolidated Carr Creek Elementary on the hill.

Together, these sources put Neely squarely within the mid twentieth century story of Appalachian public schools. Small, intimate, and often underresourced, they were nonetheless remembered as central to childhood and community life.

Carr Fork becomes Carr Creek Lake

The quiet routine at Neely did not end because of a local decision to close a “little” school. It ended because the valley itself was about to change.

After repeated flooding in the Kentucky River basin, the United States Army Corps of Engineers proposed a series of flood control reservoirs in eastern Kentucky. Carr Fork Lake, later renamed Carr Creek Lake, became one of those projects.

According to the Corps and later summaries, the dam on Carr Fork near Littcarr created a 710 acre reservoir, with an earth and rock fill dam 130 feet high and 720 feet long. It was designed and built by the Louisville District as part of a broader Ohio River basin flood risk reduction plan and also promised water quality improvements and recreation.

The Carr Creek Oral History Project’s finding aid at Berea College quotes a 1973 Corps study that laid out the human cost of that engineering. The project would require relocating 271 families, 30 businesses, three schools, six churches, and 19 cemeteries in Knott and neighboring counties.

In practice, that meant that entire communities such as Smithsboro would end up beneath the new lake, their homes and churches remembered only in photographs and in genealogical sites that document which family cemeteries had to be moved.

Neely Elementary did not sink beneath the reservoir, but its fate was tied to these larger changes. As water backed up into the narrow valley and new highways climbed above the pool, school buildings that once sat at the center of small attendance districts no longer made sense on a map devised for bus routes that circled a lake rather than following a creek.

Three schools into one

Joe Hall’s oral history offers the clearest on the ground account of how Neely was folded into the new school landscape. Speaking from a house near the Carr Creek marina, he remembers attending the “old” Carr Creek Elementary in the community of Cody before construction began. As the dam and new highway took shape, county officials decided to consolidate three valley schools.

“There was the old Carr Creek Elementary, there was Yellow Creek, and Neely,” he tells interviewer Nicole Musgrave. All three were closed and their students sent to a new Carr Creek school “on the hill” above the future lake. Class sizes jumped to roughly forty five students per room, with multiple sections of each grade.

Hall locates the Yellow Creek school building along Route 160 and notes that its stone structure is now used as a church. The Neely building, he explains, still stands up Yellow Creek below Building Mountain, across from Roosevelt Honeycutt’s old store, and like Yellow Creek it has seen new religious and community uses in the decades since the last school day.

His account matches the broader pattern described in the Corps documents and Berea’s collection guide. Elementary schools like Neely were part of the three school figure in the 1973 relocation study, and their closure formed just one small piece of the social cost that does not show up in neat tables of acre feet and cost benefit ratios.

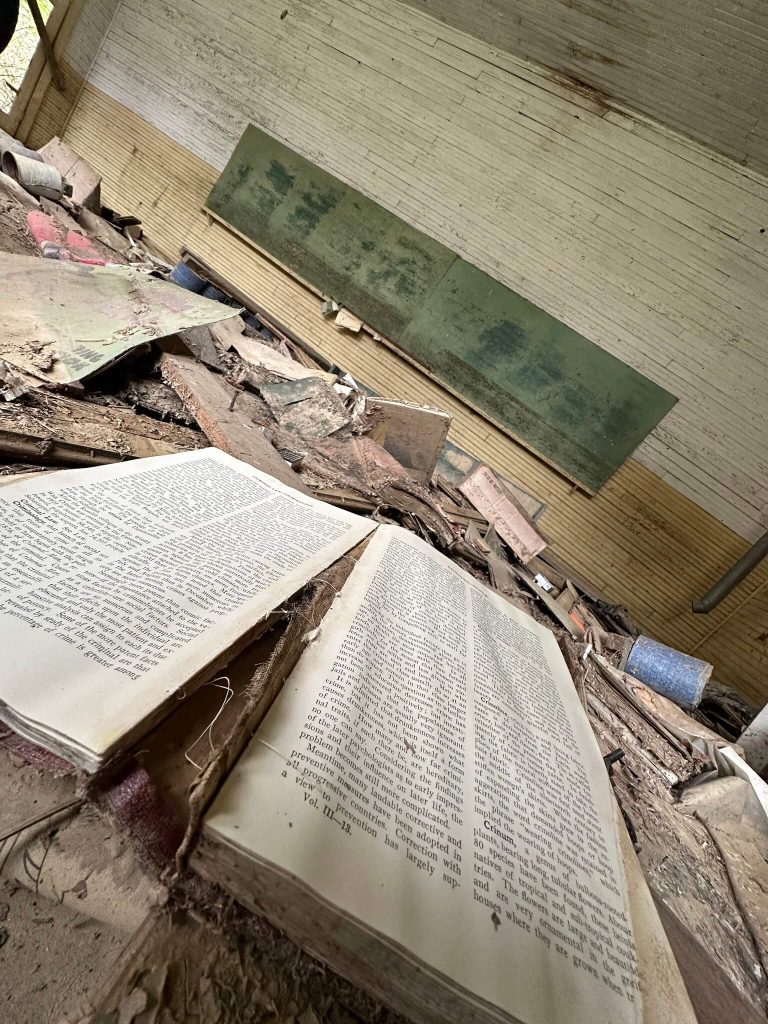

A schoolhouse Abandoned

Golden Glen Hale’s interview picks up the story after consolidation. He recalls the closure of Neely Elementary as part of the dam project and describes efforts to keep the building from falling into complete disuse. The NOAA abstract credits him with helping to try to repurpose the schoolhouse for community events, a detail that hints at fish fries, meetings, and church services that may never appear in formal minutes yet kept the structure alive. However the building is abandoned currently.

Online traces confirm that local people have continued to see Neely as worth saving. A Facebook post from the Knott County Historical and Genealogical Society showing another “relict” school on Upper Mill Creek urges that the building should be preserved “just like the Neely School,” a casual comparison that assumes everyone knows Neely as a landmark.

The home video of “Old Neely School” does the same work. Children’s voices and family commentary over shaky footage turn what might look like an abandoned stone box into a site of memory. The filmer’s mother, who attended Neely in the 1960s, is present in that act even when she stays behind the camera.

Neely therefore fits neatly into the theme of Abandoned Appalachia but could maybe be repurposed. Its bell no longer rings for morning classes, but the structure and the ground around it continue to serve as a gathering place and a visual reminder that an older Carr Fork landscape existed before the lake.

Neely in the wider story of Appalachian education

Set against the larger arc of Appalachian education, Neely Elementary helps bridge two well documented eras. On one side stands the reform minded world of the settlement schools, exemplified in Knott County by Hindman Settlement School at the Forks of Troublesome Creek. Historian Jess Stoddart has shown how Hindman’s teachers and staff blended classroom instruction, health work, and agricultural extension in an attempt to modernize rural life.

On the other side lies the mid to late twentieth century drive toward consolidation, in which county boards merged scattered one room schools into larger elementaries and high schools, often aided or forced by federal highway and dam projects. Scholars such as Eloise Jurgens have argued that the settlement schools were early models for integrated services, but by the time of Carr Creek Lake the leading role in reshaping communities had passed to agencies like the Corps of Engineers.

Neely sits in the overlap of those stories. Its teachers, including young educators like Lula Mullins, worked in a system influenced by settlement school ideas. Its closure and repurposing, on the other hand, were dictated by federal flood control policy and the economics of school transportation.

The Carr Creek Oral History Project makes clear that reactions to the lake remain mixed. Some narrators appreciate the flood protection and recreation that Carr Creek Lake provides. Others mourn the loss of farms, cemeteries, and schools.

What is beyond dispute is that Neely Elementary occupies a small but important place in that story. It was one of three schools named in local memory as “taken” by the dam and consolidation. It nurtured students who went on to teach in the region and fight to keep local history alive. And even in its altered form, it offers a rare chance to stand in front of a former rural schoolhouse and see both an older creek valley and a modern reservoir at once.

Why Neely still matters

For historians and community members alike, Neely Elementary offers several paths for future work.

The Carr Creek Oral History Project at Berea College and NOAA continues to grow, with twenty interviews already available and more local voices to be recorded. Careful listening for “Neely,” “Nealy,” and Yellow Creek in those transcripts can help map family movements and schooling patterns around the future lake.

County school board minutes, teacher registers, and school censuses at the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives and in Knott County offices can help pin down Neely’s opening and closing dates and trace teachers like Lula Mullins across their careers.

Local photograph collections, especially the Knott County pictorial history volume and the holdings of the Knott County Historical and Genealogical Society, almost certainly contain class pictures and building shots that can put faces to the names preserved in oral history.

In the meantime, the old stone building on Yellow Creek continues to do what so many Appalachian structures do after official use ends. It waits. It hosts revival meetings, potlucks, and quiet visits from former students. It anchors family stories told to grandchildren who have never known the creek without a lake.

Neely Elementary may never draw the crowds that Carr Creek State Park does on a summer weekend, yet for the communities that once looked up at its windows every school day, it remains one of the most important buildings on the shore.

Sources & Further Reading

Berea College Special Collections and Archives. “Carr Creek Oral History Project” (BCA 0292) collection guide. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://bereaarchives.libraryhost.com/repositories/2/resources/779 Amazon

Federal Register. “Notice of Availability of Environmental Impact Statements” (includes the Carr Fork Lake project EIS notice and relocation figures). July 2, 1974. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1974-07-02/pdf/FR-1974-07-02.pdf OSTI

United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. Louisville District. Final Environmental Impact Statement: Carr Fork Lake Project, Kentucky (publication date February 28, 1974). Accessed December 31, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Final_environmental_impact_statement-_Carr_Fork_Lake_project,_Kentucky_-_USACE-p16021coll7-15924.pdf Wikimedia Commons

United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. Louisville District. “Carr Creek Lake Master Plan, 2022.” USACE Digital Library (CONTENTdm). 2022. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://usace.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16021coll7/id/21678/ CONTENTdm

United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. Louisville District. “Carr Creek Lake Master Plan, 2022 (Appendix B: Environmental Assessment / EA and FONSI).” 2022. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Appendix_B,_environmental_assessment_for_the_Carr_Creek_Lake_master_plan_-_USACE-p16021coll7-21677.pdf Wikimedia Commons

United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. Louisville District. “Carr Creek Lake” (project information). January 10, 2024. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://www.lrd.usace.army.mil/Mission/Projects/Article/3641111/carr-creek-lake/ USACE Great Lakes & Ohio River

United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. Louisville District. “Carr Creek Lake” (recreation information). January 10, 2024. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://www.lrd.usace.army.mil/Submit-ArticleCS/Recreation/Article/3641670/carr-creek-lake/ USACE Great Lakes & Ohio River

United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. “Carr Creek Lake – Water Data.” Accessed December 31, 2025. https://water.usace.army.mil/overview/lrl/locations/carrcreek Water Data

United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. Corps Lakes Gateway. “Carr Creek Lake (Project ID H202720).” Accessed December 31, 2025. https://corpslakes.erdc.dren.mil/visitors/projects.cfm?ID=H202720 Corps Lakes

United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. Louisville District. “USACE hosting virtual workshop for Carr Creek Lake Master Plan Update.” October 1, 2021. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://www.lrd.usace.army.mil/News/News-Releases/Display/Article/3635600/usace-hosting-virtual-workshop-for-carr-creek-lake-master-plan-update/ USACE Great Lakes & Ohio River

United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. “USACE announces public review period for Carr Creek Lake Master Plan.” DVIDS Hub, September 29, 2022. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://www.dvidshub.net/news/430368/usace-announces-public-review-period-carr-creek-lake-master-plan DVIDS

Recreation.gov. “Carr Creek Lake, Kentucky (Gateway).” Accessed December 31, 2025. https://www.recreation.gov/gateways/358 Recreation.gov

Mullins, Lula V. “Obituary information.” Scobee Funeral Home (Winchester, Kentucky), June 19, 2020. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://www.scobeefuneralhome.com/obituaries/Lula-V-Mullins?obId=15122635 Scobee Funeral Home

Rennick, Robert M. “Knott County – Post Offices.” County Histories of Kentucky (Morehead State University), 2000. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://scholarworks.moreheadstate.edu/kentucky_county_histories/237/ Morehead State Digital Archives

Jurgens, Eloise, and Russ West. “Southern Appalachian Settlement Schools as Early Initiators of Integrated Services.” ERIC (ED404097), 1996. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED404097 ERIC

Stoddart, Jess. Challenge and Change in Appalachia: The Story of Hindman Settlement School. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://www.kentuckypress.com/9780813122575/challenge-and-change-in-appalachia/ The University Press of Kentucky

“YouTube video: ‘Old Neely School, mom went there in the sixties, it still stands in Knott County Ky.’” YouTube. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=woT1PV4pceY YouTube

Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet, Division of Water. Final Total Maximum Daily Load for Bacteria: Carr Fork (E. coli) (TMDL report, includes watershed context). Accessed December 31, 2025. https://eec.ky.gov/Environmental-Protection/Water/Protection/TMDL/Approved%20TMDLs/TMDL-CarrForkEcoli.pdf Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet

U.S. Geological Survey. US Topo 7.5-minute map: Hindman, KY (PDF) (topographic context for Carr Fork/Carr Creek area). March 31, 2010. Accessed December 31, 2025. https://prd-tnm.s3.amazonaws.com/StagedProducts/Maps/USTopo/PDF/KY/KY_Hindman_20100331_TM_geo.pdf prd-tnm.s3.amazonaws.com

Author Note: My friend Kala Thornsbury brought me to the old Neely School, and I fell in love with the way the building looks against the mountains and the quiet beauty of the surrounding bottomland on Yellow Creek. The school has suffered flood damage over the years, but even weathered and scarred it still feels like a landmark that refuses to let this valley’s story be forgotten.

I miss that school and the there.