Appalachian Churches Series – Saint George Catholic Church in Jenkins

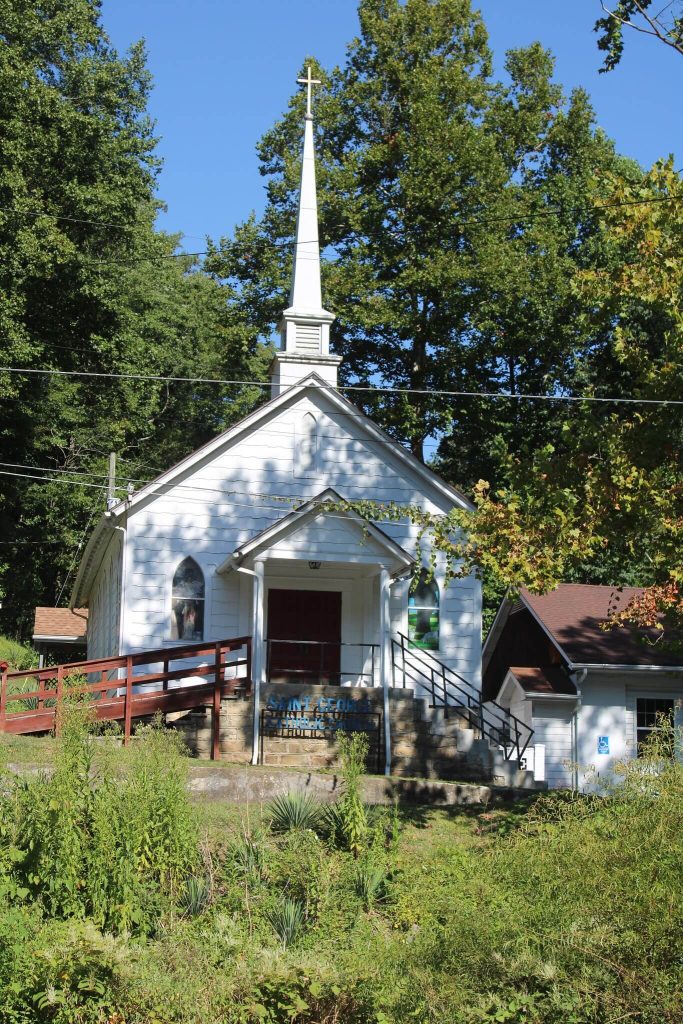

Tucked against the hillside at the foot of No. 4 Hill in Jenkins, Kentucky, St. George Catholic Church looks like a simple white frame church. It sits below company houses and above Little Elkhorn Creek, with the old Dunham High School site rising just behind it. From the road it can be easy to miss, yet for more than a century this little parish has stood at the crossroads of coal company planning, immigrant faith, African American education, and global Catholic missions.

Today St. George is one of the smallest Catholic congregations in the Diocese of Lexington. On Sunday mornings a handful of parishioners gather for Mass in a town where Catholics remain a tiny minority. The church’s story, however, reaches far beyond its size, stretching from Pittsburgh’s corporate boardrooms to the streets of Kolkata and the hills of eastern Kentucky.

A company town and a company church

Jenkins exists because of coal. In 1911 the Consolidation Coal Company purchased roughly 100,000 acres across three counties in eastern Kentucky to open a large mining complex and a model company town on Elkhorn Creek. Company planners laid out streets, built housing, opened stores, schools, a hospital, and recreational facilities for what would eventually be a community of several thousand people.

The company’s leaders knew that recruiting and retaining a stable workforce required more than houses and a pay envelope. They actively courted workers from across the United States and from immigrant communities abroad, including Catholics from Ireland, Germany, Italy, and Eastern Europe. Providing a Catholic parish became part of that strategy.

Local historian Mary Jo Wolfe recounts that by 1911 the manager of the new operation, John G. Smyth, wrote to Bishop Camillus P. Maes of the Diocese of Covington, asking the Church to investigate the needs of Catholic workers in the new town of Jenkins. Construction of a Catholic chapel was already under way by the time that letter was written. By 1914 a frame church and rectory stood along Little Elkhorn Creek on land donated by Consolidation Coal, with enough room reserved for an eventual school.

A 1914 deed in the Letcher County records confirmed the transfer of about one and a half acres at the foot of No. 4 Hollow to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Covington. That parcel would become a Catholic complex. On the lower terrace sat St. George church and rectory; above it, the company and local school board later placed the Jenkins Colored Grade School and, eventually, Dunham High School for African American students.

From its earliest years, then, St. George stood at the center of both corporate and community life, a visible sign that a northern coal company intended to provide religious institutions as part of its promised “model town.”

Early mission priests in the Kentucky River district

In its first decades St. George was less a self-contained parish than a mission station on the far edge of the Diocese of Covington. The Catholic population was scattered across company camps in Jenkins, Dunham, Burdine, and McRoberts, and priests came by train or over rough mountain roads from larger parishes on the Bluegrass side of the state.

Digitized Catholic newspapers allow us to glimpse this missionary world. In 1918 the Catholic Columbian, reporting on the silver jubilee of Rev. Louis A. Tieman, mentioned Rev. Earl Bauer as a diocesan missionary headquartered at Jenkins. That brief note hints that by the late 1910s the diocese already viewed Jenkins as a base for wider mountain evangelization.

In March 1921 another Catholic Columbian item referenced “St. George Church, Jenkins, Ky.” under the care of Rev. John McCrystal, confirming both the dedication of the church and the rotation of mission priests through the camp. A few years later, in 1928, the Catholic Telegraph printed a schedule of Forty Hours Devotions that included “St. George, Jenkins” in February alongside established parishes in the Covington diocese. Other notices identified Rev. Edward Carlin of Jenkins as in charge of the “missionary district of the Kentucky River,” signaling that the coal town had become a hub for Catholic ministry across a broad swath of eastern Kentucky.

These scattered notices, combined with parish registers and diocesan personnel lists, make it possible to sketch a prosopography of early Catholic missionaries who climbed Jenkins’s steep streets, baptized miners’ children, and rode trains up and down the Elkhorn Creek valley.

Holy Cross Cemetery and an immigrant parish

To serve its Catholic workforce, Consolidation Coal did more than build a church. Wolfe records that the company also set aside a smaller parcel on a knoll near the B and O section for a Catholic cemetery associated with St. George. Early maps labeled it Holy Cross Cemetery, and nearly sixty early graves were counted there in the twentieth century.

Today Holy Cross Cemetery appears in online burial databases as the “Catholic Cemetery (Holy Cross Cemetery), East Jenkins,” located on the hill beside Crest Hill Cemetery. The headstones bear surnames that reflect the parish’s immigrant and multiethnic roots, including Italian, German, and Eastern European families alongside local Appalachian names.

Funeral notices and local obituary records through the twentieth century show parishioners of St. George working in the mines, serving in the armed forces, and raising families throughout Letcher County. These sources are invaluable for genealogists who want to trace Catholic families in a region where Protestants were the overwhelming majority.

Sisters, hospital, and school on the hill

As Jenkins matured, Catholic institutions multiplied. Sharon Heights Hospital, built by the coal company on a hill above town, eventually came under the care of the Sisters of Divine Providence, who also helped operate a school connected with St. George. “The Way We Were” columns in the Mountain Eagle have recalled the era when the sisters staffed the hospital and school before the property was later sold.

The Dunham High School National Register nomination helps tie these pieces together. It notes that the historic Jenkins Colored School and later Dunham High School stood “on a hill, above a creek, and behind the St. George Catholic Church.” The entire 1.55 acre parcel, including St. George’s buildings and the school, was deeded to the Diocese of Covington by Consolidation Coal in 1914 and never left Catholic ownership.

The result was an unusual landscape. On a single hillside one could find an immigrant Catholic parish, a Catholic-run hospital and school at various points, and, on the rear of the lot, the only high school for African American students in Letcher County. St. George’s property became a crossroads where corporate welfare, Black education, and Catholic mission overlapped.

From Covington to Lexington

For most of its history St. George belonged to the Diocese of Covington, which oversaw Catholic life in eastern Kentucky. The Official Catholic Directory and diocesan assignment lists show Jenkins appearing as a mission or small parish administered from larger towns such as Pikeville, with a steady rotation of priests, including members of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, serving the community.

In 1988 Rome erected the Diocese of Lexington to better serve the Commonwealth’s Appalachian and Bluegrass counties. St. George passed to the new diocese along with other mountain missions. Today diocesan directories list St. George as a mission parish of St. Francis of Assisi in Pikeville, with the pastor in Pikeville also responsible for Sunday Masses and sacramental care in Jenkins.

Contemporary parish listings show that St. George still offers Sunday Mass (often at 8:30 a.m.) and weekday liturgies when a priest is available, despite the town’s sharply reduced population and the continuing decline of coal employment in Letcher County.

Mother Teresa, Father Randall, and a rural American first

In the early 1980s St. George entered global Catholic history. Father Edward Randall, an Oblate of Mary Immaculate and pastor of the parish, had long worried about the grinding poverty, isolation, and addiction he saw in the hollows around Jenkins. According to Catholic Extension, which has supported St. George for decades, Father Randall reached out to Mother Teresa of Kolkata and her Missionaries of Charity, asking whether they might consider a rural mission in the Appalachian coalfields.

The story that parishioners still tell begins with a rosebush. Father Randall and his people prayed for a sign that Mother Teresa would accept the invitation. One day the rosebush beside the little church bloomed far earlier than normal. Soon afterward, word came from Mother Teresa that she would send sisters to Jenkins. Catholic Extension presents this as the first of “three miracles” associated with St. George.

In 1982 Mother Teresa herself arrived in Jenkins to open a Missionaries of Charity convent at 44 Cove Avenue, a street once reserved for top company officials. The Mountain Eagle later marked the thirtieth anniversary of her visit in a 2012 article titled “Mother Teresa visited Jenkins 30 years ago,” recalling how local residents watched the diminutive nun bless their homes and walk the streets of the coal town.

A 2019 Associated Press feature, carried by Crux, notes that Jenkins was the first rural American mission for the Missionaries of Charity. The article describes how the sisters, mostly from India, still rise before dawn, attend Mass in neighboring towns when no priest is available in Jenkins, and spend their days visiting the poor, sick, and elderly in remote hollows.

The same story explains why the order chose this corner of Letcher County. By the early 1980s, with coal jobs already declining, church leaders in the Diocese of Covington saw Jenkins as “a forgotten and needy place” but also one that possessed a ready-made Catholic base: a small church built by the coal company years earlier to attract Irish and German workers.

Dunham High School, Black education, and “Mother Teresa, pray for us”

Behind St. George, on the uphill portion of the church lot, stood the Jenkins Colored School and later Dunham High School. The National Register nomination describes how the wooden school, built around 1916, served grades one through twelve for African American children from Jenkins, Dunham, Burdine, McRoberts, Fleming, and Haymond until school integration in 1964. After a fire in 1969 the main building fell into ruin and was eventually removed, leaving only a concrete block addition from around 1950.

That remaining addition, now painted blue and white, carries a simple inscription on its south wall: “Mother Teresa Pray For Us.” The same document notes this detail in its architectural description, underlining how the memory of St. George’s most famous visitor has been grafted onto the landscape of Black educational history in Jenkins.

The nomination argues that Dunham High School is significant for African American education, ethnic heritage, and social history in Letcher County. It emphasizes that the school stood on land deeded for Catholic purposes and that the “primary use of the parcel” remained the Catholic church complex, which at times included a parochial school. This intertwining of Catholic property, Black schooling, and coal company planning helps complicate any simple story of religion and race in the Appalachian coalfields.

Today the steep stone steps from St. George’s parking lot still climb toward the former school site. The concrete building is crumbling, its windows boarded, but the painted plea to Mother Teresa remains, connecting the experiences of Black students in the mid twentieth century with the later mission of the Missionaries of Charity on the same hill.

Quiet miracles in a struggling town

In the twenty first century Jenkins has endured the collapse of coal employment, population loss, and the opioid epidemic. The 2019 AP story from Jenkins notes that Letcher County’s poverty rate has climbed above 30 percent and that per capita incomes have fallen even as mining jobs disappeared.

Yet St. George has remained a place where small miracles, as parishioners see them, continue to unfold. Catholic Extension’s 2025 feature on the parish organizes its narrative around three such miracles.

The first is the rosebush and Mother Teresa’s decision to establish a mission in Jenkins. The second centers on the catastrophic July 2022 floods that devastated eastern Kentucky. Jenkins lay within the federal disaster zone, with water pouring down hollows and through neighborhoods. Parish stories preserved by Catholic Extension describe St. George parishioners who launched canoes and kayaks to rescue neighbors, broke down doors to save disabled residents, and pulled one woman with water up to her neck from her home. Not one person in Jenkins died in the flood.

The third “miracle” focuses on addiction and recovery. In a region wracked by substance abuse, the sisters and parish volunteers spend their days visiting prisons, rehab centers, and families torn apart by drugs. Catholic Extension highlights the story of a grandmother who adopted her five grandchildren to keep them from entering state care, nearly died from illness, then chose to have all the children baptized Catholic after experiencing support from the Missionaries of Charity.

These accounts sit alongside everyday scenes: Christmas ham distributions in the St. George social hall, summer programs for children, and quiet weekday visits by sisters who arrive with groceries, a space heater, or simply prayer. When the AP reporter visited, more than eighty residents lined up outside the convent and church hall for food and fellowship.

Saint George today

According to recent parish listings, St. George is located at 22 Dotty Lane in Jenkins, with a mailing address at Post Office Box 787. Mass time directories list a Sunday Mass at 8:30 a.m. and weekday Masses when the priest from Pikeville is in town.

Drive past the church on a fall afternoon and you will see the white frame building framed by hardwoods, its steeple rising above the roofs of company houses. Above it, the battered shell of the Dunham High School addition still bears its plea to a canonized saint. Below it, Little Elkhorn Creek runs through a town that once boomed with coal money and now limps along on nostalgia, grit, and outside help.

St. George Catholic Church is easy to miss on a map, yet its story weaves together labor history, immigrant religion, African American education, and global Catholic mission. For more than a century, miners, nurses, Black students, sisters from overseas, and a handful of local families have climbed its steep steps. The parish has never been large, but its reach extends from company boardrooms and diocesan archives to Kolkata and the hollows of Letcher County.

Sources & Further Reading

Kentucky Heritage Council. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Dunham High School, Letcher County, Kentucky. Frankfort: Kentucky Heritage Council/State Historic Preservation Office, 2025. https://heritage.ky.gov/historic-places/national-register/Documents/Letcher%20County%2C%20Dunham%20High%20School%2C%20final.pdf Kentucky Heritage Council

Letcher County Clerk’s Office. Deed Records, Book 47, Page 475 (Consolidation Coal Company to Diocese of Covington, October 12, 1914). Accessed January 3, 2026. https://letchercountyclerk.ky.gov/records Kentucky Heritage Council+1

Wolfe, Mary Jo. “E-1 St. George Catholic Church.” In The History of Jenkins, Kentucky. Jenkins, KY: Jenkins Area Jaycees, 1973. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/Kentucky/Letcher/Jenkins/_Texts/HJK/E*.html Penelope

“The Catholic Columbian.” “Kentucky News.” The Catholic Columbian (Columbus, OH), March 25, 1921. Catholic News Archive. https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=CC19210325-01.2.46 thecatholicnewsarchive.org

“The Catholic Telegraph.” “Diocese of Covington.” The Catholic Telegraph (Cincinnati, OH), February 9, 1928. Catholic News Archive. https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=TCT19280209-01.2.125 thecatholicnewsarchive.org

“The Catholic Telegraph.” “Diocese of Covington.” The Catholic Telegraph (Cincinnati, OH), January 26, 1928. Catholic News Archive. https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=TCT19280126-01.2.34 thecatholicnewsarchive.org

“Mother Teresa Visited Jenkins 30 Years Ago.” The Mountain Eagle (Whitesburg, KY), July 4, 2012. https://www.themountaineagle.com/articles/mother-teresa-visited-jenkins-30-years-ago themountaineagle.com

Kenning, Chris. “Mother Teresa’s Nuns Return to Her Rural Kentucky Mission.” Associated Press, December 24, 2019. Reprinted at LEX18. https://www.lex18.com/news/covering-kentucky/mother-teresas-nuns-return-to-her-rural-kentucky-mission LEX 18 News – Lexington, KY (WLEX)+1

Catholic Extension Society. “See the 3 Miracles of This Little Church in the Appalachian Mountains.” Stories of Faith, July 1, 2025. https://www.catholicextension.org/stories/see-the-3-miracles-of-this-little-church-in-the-appalachian-mountains Catholic Extension Society

Catholic Diocese of Lexington. “Parish Finder: St. George, Jenkins.” Diocese of Lexington Parish Directory, updated 2025. https://cdlex.org/parish-finder CDLEX – Catholic Diocese of Lexington

St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church, Pikeville. “Our Story.” Parish history page including mission relationship with St. George, Jenkins. https://stfrancispikeville.org/our-story St Francis of Assisi Catholic Church

CatholicClocks.com. “St. George, 22 Dotty Lane – Mass Times, Jenkins, Kentucky.” Accessed January 3, 2026. https://www.catholicclocks.com/mass-times/united-states/kentucky/jenkins Catholic Clocks

“Southwestern Ohio’s Saintly Visitors.” The Catholic Telegraph Magazine, May 12, 2021. https://www.thecatholictelegraph.com/southwestern-ohios-saintly-visitors/74534 Catholic Telegraph

“Letcher County, Kentucky.” Wikipedia, last modified 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letcher_County,_Kentucky Wikipedia

Author Note: Writing about St. George has reminded me how global Catholic stories and local coal camp lives have been intertwined for more than a century in one small Kentucky hollow. If your family has photographs, memories, or documents tied to this parish or to Dunham High School, I would be honored to learn from them as this Appalachian Churches series continues to grow.