Abandoned Appalachia Series – Newlee Iron Furnace at Cumberland Gap

At the base of Cumberland Mountain, where Gap Creek cuts a narrow notch toward the little town of Cumberland Gap, Tennessee, a towering block of stone rises beside the water. Locals call it the Newlee Iron Furnace. To nineteenth century engineers and travelers it was the Cumberland Gap furnace, a cold blast charcoal stack tapping the dyestone iron ore belt that runs along the western flank of the Appalachians. Today the surviving chimney sits inside Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, within the Virginia portion of the park boundary, a relic of the years when this famous pass was not just a migration route but an industrial worksite.

A Furnace on the Wilderness Road

Long before anyone stacked sandstone blocks along Gap Creek, the cut in Cumberland Mountain was a corridor for animals and people. The Warrior’s Path that Indigenous hunters followed through the pass later became the Wilderness Road, the route that carried thousands of Euro American settlers from Virginia and the Carolinas into Kentucky and beyond.

By the early nineteenth century that same geography drew investors who saw not only a gateway but a power source. Gap Creek dropped fast from the saddle of the Gap toward the Powell River. Forested slopes promised fuel. Nearby ridges in what geologists now call the Poor Valley area carried beds of crinoidal oolitic hematite in the Silurian Rockwood Formation, part of a broader dyestone ore belt that mining engineers were beginning to trace across Tennessee and into Virginia and Kentucky.

The National Register of Historic Places nomination for the Cumberland Gap Historic District identifies the furnace as a charcoal blast furnace probably built between 1813 and 1835 by Martin Beaty, a Tennessee ironmaster and later congressman. By the 1850s it appeared in national iron directories under the heading “Cumberland Gap furnace,” one of a cluster of Southern charcoal works that still relied on woodland fuel and local ore while larger furnaces in the Northeast and Midwest shifted toward coke and more centralized production.

From the beginning, the works at Gap Creek were tied to a landscape that was both frontier gateway and industrial district. Travelers who had expected only a rugged pass instead met a scene of chimneys, waterwheels, and smoke along the creek. In 1872, F. G. de Fontaine’s article “Cumberland Gap” in Appletons’ Journal paired a romantic description of the surrounding “everlasting hills” with an engraving titled “Cumberland Gap, from the East” that clearly shows mills and industrial buildings crowded into the valley floor.

Martin Beaty’s Furnace and the Birth of an Ironworks

The NRHP nomination’s inventory of contributing resources labels the surviving stack “Iron Furnace (G 63)” and reconstructs the complex as it looked around 1870. The core was a limestone chimney, twenty five by twenty six feet at the base and about thirty five feet high, lined with firebrick. To the south stood a small casting shed, roughly fifteen by twenty feet. To the north a two and one half story storehouse, thirty by forty five feet, housed a thirty foot overshot waterwheel that powered the blast machinery. Nearby, a separate “fleming mill” handled finishing work. Gap Creek itself had been forced into a cut stone flume so that water could be controlled for the wheel and the furnace kept dry.

This was not a village blacksmith’s forge but a capital intensive industrial plant. Beaty and his partners invested in stone, timber, waterworks, and ore rights. A blast furnace of this type ran for months at a time when properly supplied. The chimney was kept hot around the clock. Helpers charged ore, charcoal, and limestone flux in careful layers at the top while the waterwheel drove bellows that forced cool air into the heart of the stack, raising internal temperatures high enough to melt iron from the ore.

Even in its initial decades, the Gap Creek works were connected to distant markets. Technical directories compiled by the American Iron Association and J. Peter Lesley’s Iron Manufacturer’s Guide listed the furnace under the East Tennessee works, noting its “fossil” dyestone ore and its charcoal fuel supply. That listing placed a structure buried in the deep folds of Cumberland Mountain alongside furnaces in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York, a reminder that Beaty’s venture was part of a national network of antebellum iron.

From Cumberland Gap Furnace to Newlee Iron Works

In the mid nineteenth century a new name became attached to the furnace. The Kentucky Geological Survey field guide on Middlesboro and Cumberland Gap explains that the stone chimney now standing was constructed in 1819 and that local businessman John G. Newlee acquired the facility sometime between 1845 and 1850. Under Newlee’s ownership the complex operated as Newlee Iron Works.

Newlee’s tenure coincided with both growth and strain in the region’s economy. Coal and timber speculation in the surrounding Middlesboro Basin would not fully explode until the 1880s, but by the 1840s and 1850s roads and small towns were already knitting the Kentucky Virginia Tennessee borderlands together. The furnace drew ore from the Silurian hematite beds in nearby Poor Valley Ridge and timber from the slopes around the Gap.

As the ironworks expanded, it reshaped the settlement at the mouth of the Gap. Workers needed housing and basic services. Newlee’s storehouse and mill drew in teamsters and small merchants. By the time de Fontaine visited in the early 1870s, the “Cumberland Gap” article could assume that readers would picture not an isolated frontier notch but a hybrid place where scenic bluffs and industrial smoke coexisted in the same frame.

Charcoal, Dyestone Ore, and the Daily Work of Making Iron

Cold blast charcoal furnaces like Newlee’s were hungry machines. An interpretive National Park Service brochure on the iron industry at Cumberland Gap summarizes the standard daily “charge” used at the Gap Creek furnace in the late nineteenth century. Each day the stack might consume hundreds of bushels of charcoal, several tons of dyestone hematite ore, and well over a thousand pounds of limestone, producing roughly three tons of pig iron.

Supplying that charge took a complex labor system. Colliers felled hardwoods in the surrounding hills, stacked the cordwood into earthen mounds or kilns, then watched smoky pits for days as the wood slowly charred into lightweight fuel. Teamsters with wagons or sleds moved charcoal down rough roads to the furnace yard. Miners extracted ore from open cuts along the Rockwood Formation outcrops, breaking and sorting the rusty brown stone before it went into the stack. Limestone quarries provided the flux that would help separate metal from waste slag.

Inside the works, furnace hands endured intense heat and long shifts. Fillers climbed the stone ramp to the top of the stack with baskets or barrows of charcoal and ore. Guttermen tapped the furnace, guiding out streams of molten iron and slag. Molders and hammermen in the adjoining casting shed and fleming mill shaped some of the output into rough bars and castings. Other pig iron left as simple “pigs” or ingots, destined for blacksmith shops and foundries elsewhere in the region.

National Park Service interpreters note that an operation of this scale could employ as many as three hundred workers at peak, including woodcutters, colliers, miners, teamsters, furnace men, and support labor. Some of those jobs, especially the heavy, dangerous work of filling the stack and tending the fire, were performed by enslaved people prior to the Civil War, tying the Newlee furnace directly into the slave based industrial economy of the Upper South.

Shipping Iron Down the Powell

Although the furnace stood on the Virginia side of the line within the modern park boundary, its products moved through a tri state world. The Knoxville Focus newspaper’s overview of the site emphasizes that iron from the works supplied local blacksmiths and was also shipped down the Powell River system toward Chattanooga.

That route made geographic sense. From Gap Creek the iron could be hauled to Powell River landings, rafted down to its junction with the Clinch, and eventually into the Tennessee River. In an era when road transport over the steep ridges remained slow and expensive, water offered the cheapest way to move heavy metal, even if it meant risky trips through shoals and seasonal floods.

At the same time, smaller batches of iron stayed closer to home. Farmers and wagon makers in Bell County, Kentucky, and Lee and Claiborne Counties bought bars or castings from the works. Local histories of Bell County recall the “old iron furnace” near the modern town of Middlesboro and tie it to routes like the Harlan Road that climbed out of the Gap toward the coal fields and farming communities to the north.

War, Cannon Fire, and Reconstruction

When the Civil War reached the Cumberland Gap in 1861, the furnace and its associated buildings suddenly took on strategic value. The Gap itself became one of the most contested passes in the Appalachians. Union and Confederate forces alternately fortified and abandoned its heights, carving batteries and rifle pits into Cumberland Mountain and turning the saddle into a fortified camp.

The NRHP nomination notes that the “foundry and buildings were used for ammunition storage for a part of the Civil War.” Storing powder and shot in a cluster of stone and frame buildings along Gap Creek made sense for armies trying to move supplies through the narrow pass. It also made the complex a target.

The Kentucky Geological Survey guide’s “Iron History of the Middlesboro Region” chapter explains that the Newlee Iron Works were destroyed by Confederate forces in 1862. The same field guide’s Civil War section describes how the Union Seventh Division under General George W. Morgan occupied and then evacuated the Gap that year, blowing up an underground powder magazine on Tri State Peak in the process. In that turbulent campaign, structures near the saddle and along the approaches suffered from both deliberate destruction and collateral damage.

Yet the furnace did not die with the war. According to Andrews’s summary, reconstruction began soon after the fighting ended. The core chimney was repaired and the ironworks returned to operation under Newlee’s name. In an era when railroads and new coal fired blast furnaces were already transforming the iron industry in places like Pittsburgh and Birmingham, the reborn Newlee works represented a stubborn continuation of an older charcoal based technology in a remote mountain setting.

The Last Years of a Charcoal Furnace

By the 1870s the Cumberland Gap furnace was both archaic and unusually persistent. The National Park Service’s iron industry brochure draws on an 1880s technical account to note that the furnace’s daily output was on the order of three to slightly more than three tons of pig iron, at a cost per ton that reflected the continuing expense of charcoal and ore hauling compared to newer coke based works.

Even so, the combination of local ore, nearby timber, and modest water power kept the stack running intermittently into the 1880s. The NRHP nomination estimates that operations continued “until about 1881,” while the KGS field guide cautiously states that production extended “at least into the mid 1880s.” Both agree that the Newlee Iron Works were among the last charcoal blast furnaces in the dyestone belt to remain active.

By the turn of the twentieth century, however, the iron landscape around Cumberland Gap had shifted. New speculative capital poured into Middlesboro to the west, where developers hoped to combine local coal and iron ore in a more modern steel making venture. That attempt ultimately faltered, but its very ambition highlights how small charcoal stacks like Newlee’s no longer fit the emerging industrial economy.

Sometime in the late nineteenth century the furnace at Gap Creek went cold for good. Wooden buildings decayed or burned. The wheel rotted away. Gap Creek reclaimed portions of its bed. Only the stone chimney and a grass covered slag pile remained to mark the site of the old works.

Labor, Forests, and the Environmental Cost

The Newlee furnace’s story is not only about iron and capital. It is also about people and forests. Charcoal furnaces devoured trees. Park service interpreters emphasize that supplying hundreds of bushels of charcoal each day required constant cutting on the surrounding slopes. Woodcutters and colliers moved outward in rings from the furnace, leaving behind a patchwork of clearings, regrowth, and charcoal pits.

This cycle altered wildlife habitat and soil. Hillsides stripped of mature timber were more vulnerable to erosion and flash flooding. Repeated cutting favored certain fast growing species over others, shifting the composition of the forest. The impact was not permanent, but for decades around the mid nineteenth century the Gap’s woods were working forests geared to industrial fuel, not untouched wilderness.

The human cost is harder to quantify but no less real. Before emancipation, some of the furnace labor force consisted of enslaved men compelled to do dangerous, exhausting work around heat, dust, and heavy loads. After the war, wage laborers stepped into many of the same roles, often living in modest cabins near the works and facing the same occupational hazards with limited bargaining power. In both eras, the benefits of the iron trade flowed upward to owners and distant investors much faster than they flowed to the men who cut, hauled, and smelted the ore.

From Industrial Yard to Historic Ruin

When Cumberland Gap National Historical Park was established in the 1950s, planners quickly recognized the furnace as a key cultural resource. Park master plans and archaeological overviews mapped the site, documented the slag pile and surviving flume, and tied the ironworks into broader efforts to interpret the Wilderness Road and Civil War fortifications.

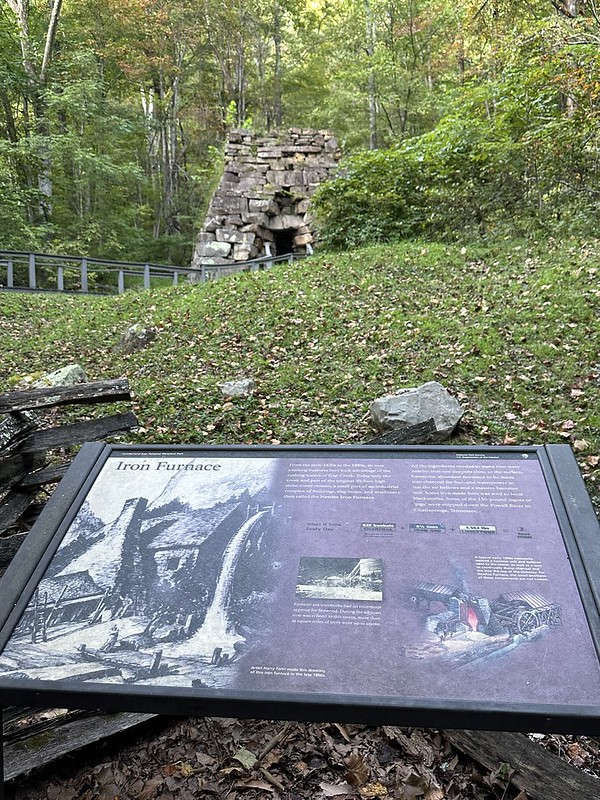

The National Register nomination in the 1980s formally listed the furnace as a contributing structure within the Cumberland Gap Historic District, noting its construction under Martin Beaty, later operation by John G. Newlee, and its status as “one of the last examples of a cold blast charcoal furnace.” Modern visitors who follow the signed trail from downtown Cumberland Gap, Tennessee, to the furnace stand where Beaty’s workers and Newlee’s crews once did, looking up at a thirty foot remnant of the chimney and down at the creek that once powered the wheel.

Outside the park bureaucracy, local historians and travelers have also helped keep the site in public memory. A roadside marker cataloged in the Historical Marker Database identifies the “Iron Furnace” near Cumberland Gap and sketches its nineteenth century history for passersby, explicitly tying the site to Lee County, Virginia. Newspaper features from outlets like the Knoxville Focus describe the furnace as one of the “most overlooked” attractions in the area and remind readers that finished iron from the Newlee works once floated down the Powell toward Chattanooga.

Today photographers frame the surviving stack against steep slopes and seasonal water, echoing the nineteenth century engravers who set the industrial complex within a dramatic mountain backdrop. The difference is that the smoke and hammer blows are gone, leaving stone, slag, and the soft hiss of Gap Creek.

Why Newlee Iron Furnace Matters

The Newlee Iron Furnace is a single industrial ruin, but it tells a layered Appalachian story. It links the famous migration corridor of the Wilderness Road to a lesser known history of antebellum and postwar ironmaking in the mountains. It ties the national dyestone ore belt and the technical literature of iron manufacturers to the very specific geology of the Rockwood Formation at Poor Valley Ridge.

It also complicates simple images of the Cumberland Gap as either untouched wilderness or purely military landscape. The same pass that saw Longhunters, settler caravans, and Civil War armies also echoed with the sound of waterwheels and casting hammers. The furnace’s reliance on enslaved and later free wage labor, its heavy draw on local forests, and its integration into distant markets show how deeply industrial capitalism penetrated even apparently remote Appalachian hollows by the mid nineteenth century.

For visitors standing inside the hollow shell of the stack today, the furnace is a place where those histories touch. The stone walls, slag, and diverted creek channel are physical records of a time when fire and iron remade both the land and the lives of the people who lived at the Gap. In a region where many industrial structures have vanished completely, the Newlee Iron Furnace remains a rare, tangible link to that charcoal powered era.

Sources & Further Reading

American Iron Association. Bulletin of the American Iron Association. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: American Iron Association, 1857. East Tennessee section entries 276–77 describe “Cumberland Gap Furnace” and “Belleville Furnace.” https://archive.org/details/bulletinofameric01amer

Lesley, J. Peter. The Iron Manufacturer’s Guide to the Furnaces, Forges and Rolling Mills of the United States. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1859. East Tennessee section repeats the Cumberland Gap furnace entry and technical specifications. https://archive.org/details/ironmanufacture00unkngoog

de Fontaine, F. G. “Cumberland Gap.” Appletons’ Journal of Literature, Science and Art 7, no. 155 (16 March 1872): 281–82. Contemporary travel sketch of the gap with references to the industrial works on Gap Creek. https://archive.org/details/sim_appletons-journal_1872-03-16_7_155

Fenn, Harry. “Cumberland Gap, from the East.” Engraving in Appletons’ Journal of Literature, Science and Art 7, no. 155 (16 March 1872), frontispiece; reprinted in Picturesque America; or, The Land We Live In. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1872–74. https://archive.org/details/sim_appletons-journal_1872-03-16_7_155/page/n0

Ahlman, Todd M., Gail L. Guymon, and Nicholas P. Herrmann. Archaeological Overview and Assessment of the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia. Knoxville: Department of Anthropology, University of Tennessee, 2005. https://npshistory.com/publications/cuga/aoa.pdf

Virginia Department of Historic Resources. “Cumberland Gap Historic District — Virginia/Kentucky/Tennessee (052-0017).” National Register of Historic Places Nomination, listed 28 May 1980. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/052-0017_Cumberland_Gap_HD_1980-1997_final_NR_combined_nominations.pdf

National Park Service. “Iron Furnace.” Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, History & Culture. https://www.nps.gov/cuga/learn/historyculture/iron-furnace.htm

Kuehn, Kenneth W., Keith A. Milam, and Margaret Luther Smath, eds. Geologic Impacts on the History and Development of Middlesboro, Kentucky. Kentucky Society of Professional Geologists Annual Field Conference Guidebook, 2003. https://studylib.net/doc/14468631/geologic-impacts-on-the-history-and-development-of-middle

Crawford, T. J., and A. H. Hunsberger. Geology of Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. Kentucky Geological Survey, Map and Chart 199, 2011. https://kgs.uky.edu/kgsweb/olops/pub/kgs/mc199_12.pdf

“Newlee Iron Furnace.” Abandoned Online. February 7, 2024. https://abandonedonline.net/location/newlee-iron-furnace/

Author Note: As someone who studies how industry reshaped the Appalachian borderlands, I am drawn to places like the Newlee Iron Furnace where stone, slag, and creek water still hold the memory of hard work and risk. I hope this piece helps you see that chimney not just as a picturesque ruin beside Gap Creek, but as a window into the people and landscapes that built the modern Cumberland Gap.