Forgotten Appalachia Series – Dunham High School: Letcher County’s Only Black High School in Jenkins, Kentucky

If you drive up No. 4 Hollow above Jenkins today, the road climbs past St. George Catholic Church and a handful of houses before it levels off on a narrow shelf of ground. Here, on a bend in the hollow, a low concrete-block wing stands in the weeds. One classroom wall is painted with the outline of a saintly figure and the words “Mother Teresa Pray For Us,” a reminder of the years when the building served as a mission chapel after its school days were over.

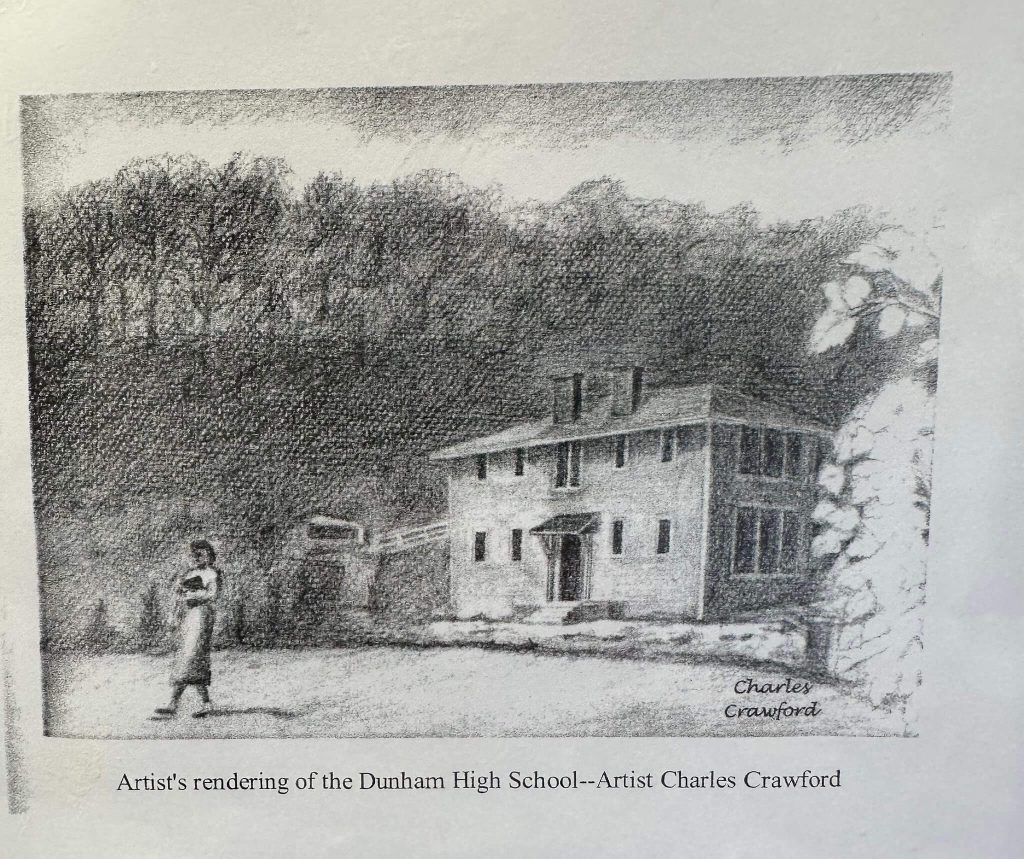

To most passersby, it looks like an abandoned outbuilding. Archival work and community memory tell a different story. That small annex is the surviving piece of Dunham High School, the only Black high school that Letcher County ever had, and a rare surviving physical reminder of Black coal camp life in eastern Kentucky. The recently listed National Register of Historic Places nomination for Dunham High School identifies the block wing as a 1950 addition built for home economics and typing that once adjoined a larger two story frame building used for Black elementary and high school students.

From the early 1930s until 1964, Dunham High School served Black students from across the Jenkins Independent School District and beyond. Young people came up this hollow from Jenkins, McRoberts, Fleming, Haymond, and smaller coal camps and hollows in Letcher County. A state historical marker now standing near the site remembers that Dunham High School opened in 1931 as the only high school for Black students in the county, remained open a full decade after Brown v. Board of Education, and was destroyed by fire in 1969.

Reconstructing the history of this out of the way place means following a paper trail that runs from coal company files and board of education minutes to state reports, local newspapers, oral history, and new scholarship on Black life in the coalfields. Those sources reveal how a segregated coal camp school became a lifeline for Black families who insisted on better schooling for their children, how it weathered the transition to desegregation, and why alumni and descendants have worked so hard to pull its story back into public view.

Coal camps, “colored town,” and a new school district

Dunham High School cannot be separated from the coal town that created it. In 1911 and 1912, Consolidation Coal Company bought a huge tract of land in Letcher and neighboring counties and laid out the model coal town of Jenkins, along with satellite camps like Dunham, Burdine, and McRoberts.

Within a few years the company had built rows of worker housing, company stores, churches, and schools. It also created a separate school system. The History of Jenkins, Kentucky, a community history published in 1973, notes that the Jenkins Graded School District was organized on August 15, 1912, with three subdivisions: Burdine, Jenkins, and Dunham. At the time there were 490 school age children in the district, and Consolidation built the original school buildings. The district employed eighteen teachers, seven at the central school at Jenkins, three at the branch school at Dunham, and four at the branch school at Burdine. McRoberts, at first, maintained its own separate schools.

Like most company towns of the period, Jenkins and its camps were racially segregated. Consolidation recruited Black miners and their families from other parts of Kentucky and from the Deep South. Historians of Black coalfield life in Appalachia, such as William H. Turner and Ronald L. Lewis, have shown how companies often clustered Black families in separate neighborhoods, sometimes called “colored town,” and provided separate church and school buildings.

In Jenkins and Dunham, company and school district records refer to multiple “colored schools.” Early photographs from the Consolidation Coal Company collection show a small frame building labeled “Colored School Building – Jenkins” and another structure in Dunham listed as “Colored School Building 207.” The Dunham High School National Register nomination matches these images to the early Black graded schools that fed into the later high school, making clear that Black education in the camp predated the creation of a full high school.

Dunham graded schools and the push for a Black high school

By the late 1920s, Black children in Jenkins and the surrounding coal camps had access to segregated graded schools through at least the eighth grade, but there was still no high school for Black students in Letcher County. The Notable Kentucky African Americans Database entry on “African American Schools in Letcher County, KY” notes that before Dunham High School opened, Black students seeking secondary education had to leave the county or quit formal schooling after the grades offered in the coal camp schools.

In 1933 the Kentucky Educational Commission issued a report that called attention to the uneven provision of high schools for Black students and suggested that small counties could contract with nearby independent districts to provide secondary education. Around the same time, in 1936, the state strengthened its requirement that Black children be provided schooling through twelve grades on terms comparable to whites, at least on paper. The Jenkins Independent School District minutes from the mid 1930s, drawn on heavily in the Dunham High School nomination, show the board wrestling with how to respond.

Those minutes record a series of decisions that reshaped Black schooling in the camps. Trustees approved plans to expand the existing Jenkins Colored School in No. 4 Hollow from a small graded school into a combined elementary and high school, serving grades one through twelve. They negotiated with the Letcher County Board of Education for the county to pay tuition to Jenkins for Black high school students, a rare instance in which a small county relied on a coal camp school as its only Black high school.

A 1939 master’s thesis by Frances Rolston, “History of Education in Letcher County, Kentucky,” provides a snapshot of this transitional period. Rolston identified Dunham Colored High School, under the Jenkins system, as the only Black high school serving the county and used its enrollment and facility statistics to illustrate how the county met its legal obligations under segregation.

At roughly the same time, there were white graded schools in the camp of Dunham itself and in other parts of the district. History of Jenkins preserves the memory of a white branch school at Dunham whose principal, Esther Lilly Clere, oversaw a staff of three teachers, while McRoberts and Burdine had their own buildings. The early white school in Dunham proper sat near the coal plant and tipple. According to the later state historical marker text, the noise and dust from the plant eventually led officials to close that school and consolidate its students elsewhere. The Black graded and then high school on the hill above St. George took on an increasingly central role.

Building and expanding Dunham High School

The site that most people now associate with Dunham High School took shape in stages. Consolidation Coal initially erected the Jenkins Colored Grade School on the bench above St. George sometime around 1916. Company photographs and the National Register nomination describe a frame structure on a raised foundation, with multiple classrooms and a small cloakroom, typical of coal camp schoolhouses of the era.

In the early 1930s, as Jenkins and Letcher County moved to establish a Black high school, the board of education minutes show the district requesting additions and improvements to the existing building. By the end of the decade, Dunham High School operated here as a combined elementary and high school. The Kentucky Historical Society’s marker summary states plainly that Dunham High School opened in 1931, educating students from Jenkins, McRoberts, Fleming, and Haymond, and remained the county’s only Black high school for the next three decades.

Enrollment at Dunham reflected the growth and instability of coal. In good years, the school drew dozens of teenagers from company housing scattered along Elkhorn Creek and up side hollows. In lean years, when mines cut shifts or families followed work elsewhere, classes shrank. The Notable Kentucky African Americans Database notes that the school’s status as the only Black high school in the county meant that, whatever the coal market was doing, Black families who stayed in Letcher County had little choice but to send their children up the hollow to Dunham if they wanted a high school diploma.

In 1950, Dunham High School reached another turning point. Board minutes and oral histories, summarized in the National Register nomination, describe how home economics classes for Black girls were being conducted in an adapted coal camp house when a student was burned in an accident involving a stove. The incident galvanized Black parents, who pushed the Jenkins board for safer, purpose built facilities. In response, the district built a two room concrete block addition that joined the frame school along its east side. One room housed a home economics lab and the other a typing and business classroom.

That modest annex, built because a community refused to accept hand me down conditions for their children, is the part of Dunham High School that still stands.

Everyday life in a Black coal camp school

Because Dunham High School was both a neighborhood elementary school and a county wide high school for Black students, it functioned as a community hub. Alumni interviewed by Carolyn Hollyfield Rodgers for a series of Mountain Eagle columns in 2021 remember the building as a place where school life and social life intertwined. They describe the grade school rooms on the lower floor, high school classrooms upstairs, and the home economics and typing spaces in the addition. They recall teachers who lived nearby, church events that spilled into the school, and commencement exercises that drew families from all over the district.

Old Mountain Eagle clippings, reprinted in “Way We Were” features and in special Dunham school columns, help flesh out that everyday world. Commencement programs and class photographs show graduating classes in the 1940s and 1950s, sports teams in handmade uniforms, and club officers standing stiffly in front of the frame building.

A community compiled video titled “Dunham High School 1931–1964,” shared online and in local social media groups, strings together many of those images. Viewers see students posed on the hillside in their caps and gowns, shots of the school bus that brought in teenagers from outlying camps, and images of the building in different seasons.

Historians have begun to use these memories and images to rethink long held stereotypes about Black life in Appalachia. Kristan L. McCullum’s 2021 article in History of Education Quarterly, “‘They Will Liberate Themselves’: Education, Citizenship, and Civil Rights in the Appalachian Coalfields,” uses oral histories from Black residents of Jenkins, including Dunham alumni, to show how families saw education as a path to freedom and citizenship. McCullum emphasizes that Black Appalachian communities were not passive recipients of Jim Crow policies but active agents who organized, strategized, and sometimes protested to expand educational opportunities.

In a 2024 Journal of Appalachian Studies article, “You Will Always Be: Remembering a Historically Black School in the Mountains of Eastern Kentucky,” McCullum turns directly to Dunham as a case study. She argues that Dunham High School functioned as a “site of memory” where Black students experienced both the wounds of segregation and the strength of a tight knit school community. Alumni remembered teachers who demanded excellence, principals who navigated between coal company officials and Black parents, and a school identity strong enough that, decades after the building burned, people still refer to themselves proudly as “Dunham graduates.”

Segregation, late desegregation, and a school in limbo

Dunham High School’s history also reflects the slow and contested road to school desegregation in Kentucky. Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 declared segregated public schools unconstitutional, yet Dunham remained in operation as a segregated Black high school for another decade.

Jenkins Independent School District board minutes from the 1950s and early 1960s, as summarized in the Dunham nomination and McCullum’s scholarship, show that Black parents and community leaders repeatedly pressed the board to either improve Dunham’s facilities or open up white schools to Black students. In 1960 the board called a “discussion meeting with the Negro citizens” to hear their concerns. That meeting, mentioned in the nomination, came at a moment when Kentucky officials were publicly touting desegregation while many local districts quietly stalled.

Ultimately Jenkins chose a delayed path to integration. A Mountain Eagle feature on Dunham students notes that in June 1964, Dunham High School was “required to close because of the desegregation of schools.” After the high school closed, Black high school students from the Dunham attendance area began attending Jenkins High School. The Dunham building continued for a time as an elementary school for Black students, then as overflow classroom and community space.

The Kentucky Historical Society’s marker text and local recollections agree that the building met its final end in 1969, when a fire destroyed the original frame structure. The cause was never definitively established in the sources available, but by the time the smoke cleared, only the 1950 concrete block addition was left standing on the hillside.

Erasure, memory work, and a return to the public record

For decades after the fire, Dunham High School almost disappeared from public memory outside Black alumni circles. County histories and school pamphlets written in the 1970s and 1980s tended to focus on Jenkins High School’s athletic records and marching band, or on the changing fortunes of the coal industry, with little reference to the segregated Black high school up the hollow.

That quiet erasure fits what writers like Clarence Wright, in his 1973 essay “Black Invisibility—Myth or Reality?,” described as a pattern of Black Appalachian histories being acknowledged only faintly, if at all, in mainstream regional narratives.

In the last twenty years, however, alumni, local historians, and scholars have worked together to bring Dunham back into the story. The Notable Kentucky African Americans Database added an entry on “African American Schools in Letcher County, KY” that names Dunham Colored High School and traces its years of operation. The Letcher County Historical and Genealogical Society has printed articles and reminiscences about Jenkins and Dunham schools in its Letcher Heritage News, and hosted programs where former students share their memories.

In 2021, Carolyn Rodgers’s series of Mountain Eagle columns on Dunham High School, along with features such as “Dunham High School students” and “Dunham High School memories,” gave the school sustained coverage in the county newspaper and generated a wave of Facebook sharing and family photo posts. The same year, alumni and supporters worked with the Kentucky Historical Society to secure a state marker, dedicated in August 2021 near the school site.

Most recently, the Kentucky Heritage Council sponsored and approved the Dunham High School nomination to the National Register of Historic Places, accepted in early 2025. That document, written by historian and Dunham alumna Carolyn Hollyfield Rodgers, gathers board minutes, company records, oral histories, and modern scholarship into a detailed narrative of the school’s origins, physical evolution, and significance. It recognizes the surviving 1950 addition not for its architecture alone, but for what it represents: Black Appalachian communities insisting on better educational spaces for their children, even within the constraints of segregation.

Why Dunham High School matters

Dunham High School’s story carries weight far beyond one hollow in Letcher County. On one level, it is a local tale of a coal company town, a separate Black neighborhood, and a hard won high school that served generations of students before closing in the wake of belated desegregation.

On another level, Dunham challenges easy myths about Appalachia as a region without Black history. Scholars like McCullum have argued that stories like Dunham’s are essential to understanding how Black Appalachians used education as a tool for freedom, citizenship, and migration choices. The Black families who sent their children up No. 4 Hollow were not invisible. They organized parent teacher associations, pressed the board of education for new classrooms and teachers, and debated desegregation with local officials.

Dunham also invites comparison with other Black high schools across Kentucky. Works like George C. Wright’s A History of Blacks in Kentucky and Turner and Cabbell’s Blacks in Appalachia show that Black communities in coal towns from Harlan County to eastern West Virginia built their own institutions in the face of discrimination, and that those institutions often vanished from public memory once integration came.

Standing on the old bench above St. George, it takes imagination to see the full complex that once stood here: the frame schoolhouse, the block wing where girls learned to cook and sew and students clacked away at typewriters, the ball field and schoolyard just beyond. Yet the records are clear, the photographs abundant, and the memories alive.

The concrete block addition that remains is not much to look at, but it belongs to a larger landscape of Black educational sites in the Appalachian coalfields. Preserving its story, and the stories of the people who learned and taught there, helps make sure that Dunham High School “will always be,” not just in the memories of its alumni, but in the written and public history of the mountains.

Sources & Further Reading

Jenkins Independent School District. Board of Education Minutes, 1912–1969. Jenkins Independent School District Records, Jenkins, Kentucky. Cited and excerpted in Carolyn H. Rodgers, “Dunham High School,” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Kentucky Heritage Council, 2025. https://heritage.ky.gov/historic-places/national-register/Documents/Letcher%20County%2C%20Dunham%20High%20School%2C%20final.pdf Kentucky Heritage Council

Rolston, Frances. “History of Education in Letcher County, Kentucky.” Master’s thesis, University of Kentucky, 1939. Notable Kentucky African Americans Database (NKAA), University of Kentucky Libraries, item 300002739. https://nkaa.uky.edu/nkaa/items/show/300002739

State Department of Education (Kentucky). Report of the Kentucky Educational Commission. Frankfort: State Department of Education, 1933. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.%24b64330 Amazon

“African American Schools in Letcher County, KY.” Notable Kentucky African Americans Database. University of Kentucky Libraries, updated 2022. https://nkaa.uky.edu/nkaa/items/show/2642 Kentucky Heritage Council

“African American Schools, High Schools – Eastern Kentucky.” Notable Kentucky African Americans Database. University of Kentucky Libraries. https://nkaa.uky.edu/nkaa/items/show/2692 NKAA

Bramel, Alli Robic. “Dunham High School.” ExploreKYHistory, Kentucky Historical Society. https://explorekyhistory.ky.gov/items/show/900 Explore Kentucky History

“Dunham High School.” The Historical Marker Database (HMdb.org), marker text for Kentucky state marker. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=212050 HMDB

Rodgers, Carolyn Hollyfield. “Dunham High School.” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. Frankfort: Kentucky Heritage Council, 2025. https://heritage.ky.gov/historic-places/national-register/Documents/Letcher%20County%2C%20Dunham%20High%20School%2C%20final.pdf Kentucky Heritage Council

Rodgers, Carolyn. “Dunham High School.” The Mountain Eagle (Whitesburg, KY), January 27, 2021. https://www.themountaineagle.com/articles/dunham-high-school/ The Mountain Eagle

Rodgers, Carolyn. “Memories of Dunham High School.” The Mountain Eagle, April 28, 2021. https://www.themountaineagle.com/articles/memories-of-dunham-high-school/ The Mountain Eagle

Rodgers, Carolyn. “Dunham School News: Commencement Exercises Held at Dunham Colored School.” The Mountain Eagle, February 10, 2021. https://www.themountaineagle.com/articles/dunham-school-news/ The Mountain Eagle

“The Way We Were: ‘The Letcher County colored schools from Haymond, Fleming, and McRoberts joined Dunham School last Friday…’” The Mountain Eagle, March 18, 2020. https://www.themountaineagle.com/articles/the-way-we-were-647/

Jenkins Area Jaycees. The History of Jenkins, Kentucky. Jenkins, KY: Jenkins Area Jaycees, 1973. Digitized edition, section D-1 “School and Sports.” https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/Kentucky/Letcher/Jenkins/_Texts/HJK/D*.html Kentucky Heritage Council

“Interview with Judge John Abbott.” In The History of Jenkins, Kentucky. Jenkins Area Jaycees, 1973. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/Kentucky/Letcher/Jenkins/_Texts/HJK/G/Abbott*.html

Pittsburgh Consolidation Coal Company. “Pittsburgh Consolidation Coal Company Photographs and Other Materials.” Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Collection NMAH.AC.1007. https://sova.si.edu/record/NMAH.AC.1007 SOVA

“Consolidation Coal Company Photographs Negative Inventory.” Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Collection AC1007. PDF inventory. https://amhistory.si.edu/archives/AC1007_negativeinventory.pdf National Museum of American History

“Dunham High School 1931–1964.” YouTube video, Kentucky Tennessee Living channel, about 11 minutes. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nl6x-PR1vwg YouTube

“Letcher Heritage News.” Letcher County Historical and Genealogical Society. Semiannual local-history periodical, various issues. Index at https://sites.rootsweb.com/~kyletch/lchgs/lhn_ndx.htm RootsWeb

“University of Kentucky Photo Collections Yield Exhibit on Lives of Blacks.” Lexington Herald-Leader (Kentucky.com), February 17, 2013. https://www.kentucky.com/news/local/education/article44404158.html Kentucky

McCullum, Kristan L. “(Re)locating Sites of Memory in Appalachia Through Black Spaces and Stories.” Black Perspectives (African American Intellectual History Society), December 10, 2021. https://www.aaihs.org/relocating-sites-of-memory-in-appalachia-through-black-spaces-and-stories/

Scholarly and contextual works

McCullum, Kristan L. “‘They Will Liberate Themselves’: Education, Citizenship, and Civil Rights in the Appalachian Coalfields.” History of Education Quarterly 61, no. 4 (2021): 449–477. https://doi.org/10.1017/heq.2021.46 Kentucky Heritage Council

McCullum, Kristan L. “‘You Will Always Be’: Remembering a Historically Black School in the Mountains of Eastern Kentucky.” Journal of Appalachian Studies 30, no. 1 (2024): 42–65. https://scholarlypublishingcollective.org/uip/jas/article/30/1/42/390182 Scholarly Publishing Collective

Sexton, Shirley B., and Grayson Shamarra Holbrook. Schools of Letcher County, Kentucky: Past and Present. 2 vols. [n.p.], 2021. Copy available at Letcher County Public Library (Whitesburg, KY).

Turner, William H., and Edward J. Cabbell, eds. Blacks in Appalachia. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1985. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_appalachian_studies/7 Core

Turner, William H. The Harlan Renaissance: Stories of Black Life in Appalachian Coal Towns. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2021. https://wvupressonline.com/node/887 West Virginia University Press

Lewis, Ronald L. Black Coal Miners in America: Race, Class, and Community Conflict, 1780–1980. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1987. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_labor_history/2 uknowledge.uky.edu

Wagner, Thomas E., and Philip J. Obermiller. African American Miners and Migrants: The Eastern Kentucky Social Club. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004. https://www.bibliovault.org/BV.book.epl?ISBN=9780252071645 bibliovault.org

Wright, George C. A History of Blacks in Kentucky, Volume 2: In Pursuit of Equality, 1890–1980. Frankfort: Kentucky Historical Society, 1992.

Wright, Clarence. “Black Invisibility – Myth or Reality?” Black Appalachian Viewpoints 1, no. 1 (1973): 1–3.

Perry, L. Martin. “Coal Towns in Eastern Kentucky, 1854–1945.” Historic context study for coal-company communities including Jenkins and Dunham. Frankfort: Kentucky Heritage Council. https://heritage.ky.gov Kentucky Heritage Council

Author Note: I did not know about Dunham High School until visiting the David A. Zegeer Coal-Railroad Museum in Jenkins, Kentucky. Once I learned its story, I wanted to write about it and help keep it visible.