Repurposed Appalachia Series – Koppers Store for the Houston Coal Company

In the bend of U.S. 52 at the mouth of Carswell Hollow, where Elkhorn Creek squeezes between highway and hillside, a brick building still holds its ground. The Houston Coal Company Store, better known to generations of miners’ families as Koppers Store, watched the rise and fall of one of McDowell County’s coal camps and has outlived the company town that once depended on it. Today it stands as one of the most intact coal company stores in southern West Virginia and as a place where local people are trying to tell the story of coal country on their own terms.

A showpiece for a coal camp

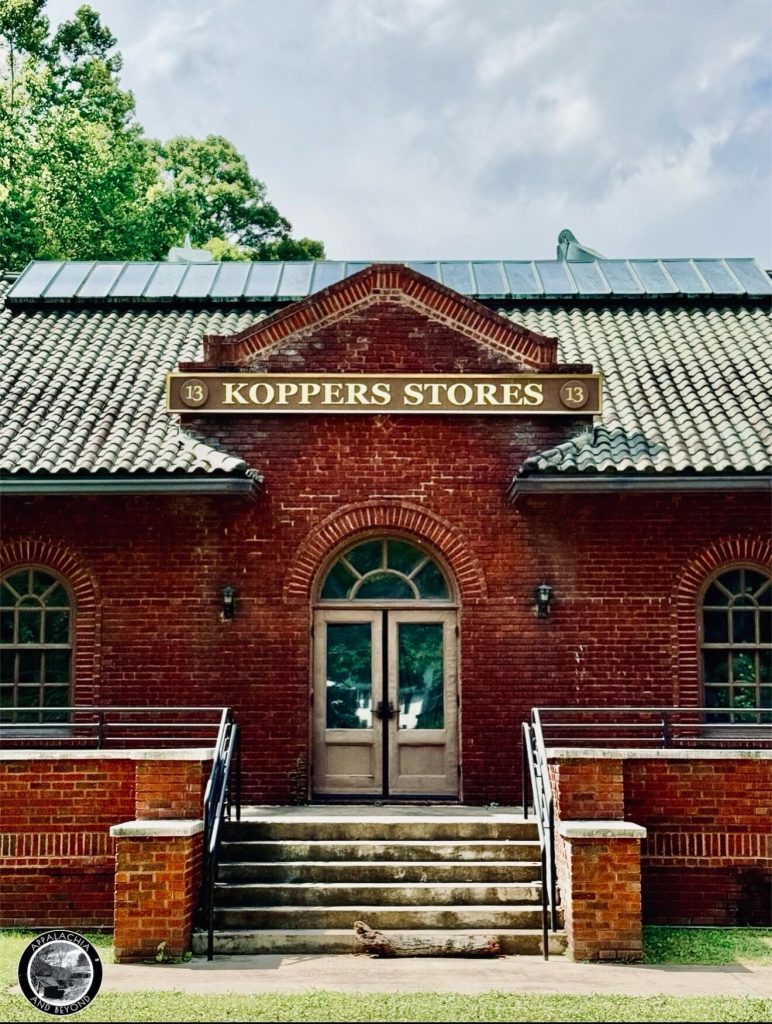

The store went up in the early 1920s, usually dated to about 1923, as part of the Houston Collieries and Houston Coal and Coke operations at Carswell. Unlike the cramped frame stores that lined many hollows, this one was conceived as a showplace. The National Register of Historic Places nomination describes a long, low, L-shaped building of dark red brick, its near-perfectly symmetrical front marked by a central entrance pavilion and rhythmic rows of tall, round-arched windows. A broad hipped roof once carried green clay tile and still rises above a lawn that separates the store from the road.

Architectural historian S. Allen Chambers notes that the store and the owner’s residence across the road were designed by Cincinnati architect E. C. Burroughs. Both buildings share materials and stylistic influences, with the house leaning more toward Tudor Revival while the store presents a simplified Renaissance Revival face to the highway. The result is a structure that looks more like a civic building or small bank than a company commissary. Arched fenestration, masonry detailing, and the deep roof give the store a restrained elegance that must have impressed visitors arriving by automobile or along the Norfolk and Western line.

Inside, the store combined practical functions with that display of prosperity. The nomination and later summaries describe a retail floor that held groceries, dry goods, and household supplies, along with a post office, payroll office, and company offices. Storage rooms and service spaces tucked under the roof and along the rear arcade allowed goods to move in from rail and road without disturbing the polished front lawn. This was a building meant to discipline circulation and to remind miners and their families who owned the landscape around them.

Carswell Hollow and the town behind the façade

If the front lawn faced the highway and the outside world, the back of the store faced up Carswell Hollow toward the camp whose wages stocked its shelves. Coal Heritage survey work for the National Coal Heritage Area describes Carswell Hollow as an unincorporated coal camp established in 1915 by Houston Collieries. The company built rows of houses for miners and supervisors along the hollow, while company president David E. Houston placed his own house on a knoll above the entrance where he could look out over both the store and the camp.

Historic Sanborn fire insurance maps and U.S. Geological Survey topographic quadrangles for Welch and Keystone show how the store sat at a kind of hinge in the landscape. On one side lay the commercial strip and rail corridor at Kimball, a growing coal town on Elkhorn Creek. On the other, Carswell Hollow narrowed quickly into a classic camp setting of clustered houses, coal tipples, and mine entries pressed against the hillside. The store occupied the flat ground where hollow met river and where the main road and the spur up Carswell converged.

Marker text preserved by the Town of Kimball explains that from the beginning the Houston Company Store housed the post office, payroll office, and retail space that served employees and their families. It quickly became a gathering place where people collected mail, lined up for pay, and swapped news. In a hollow where nearly every structure belonged to the company, the store was both the economic heart and the social crossroads of camp life.

Houston, Koppers, and the work of the Carswell mines

Carswell’s mines were part of the Pocahontas coalfield that helped fuel American industry in the early twentieth century. In those years companies competed not only over seams and markets, but also over labor. Coal companies built supposedly self-contained communities with housing, schools, churches, and stores to attract and control a stable workforce. The Houston store at Carswell fit that pattern.

The mines themselves had a dangerous history. State mine disaster lists record a July 18, 1919 explosion at the Carswell mine, then operated by Houston Collieries, that killed seven miners. Two decades later, on January 22, 1941, another explosion at the Carswell mine, by then part of the Koppers Coal Company, killed six more men. A federal investigation by the U.S. Bureau of Mines studied dust samples and ventilation patterns, and a modern compilation of the report along with marker text places the disaster squarely at the camp whose families used Koppers Store and whose dead would have been mourned in its shadow.

At some point between the 1920s and early 1930s, Houston sold his Carswell operation, including the store, to Koppers of Pittsburgh. The Town of Kimball, Clio entry, and National Register materials agree that Koppers operated the store for several decades, roughly from 1930 into the 1960s. Under Koppers, the building took on the name many locals still use. A 1929 photograph in the Norfolk and Western Railway collections shows “Koppers Store, Kimball, West Virginia,” with automobiles parked out front and the long façade busy with customers, a rare primary glimpse of the store in full operation.

Inside the system of scrip and credit

Company stores like this one are often remembered solely as instruments of exploitation. There is truth in that memory. Coal companies paid workers in a mix of cash and scrip, extended credit that tied families to the mine, and set prices that workers could not easily contest. Essays in the West Virginia Encyclopedia on company towns and stores point out that owners justified the system as a convenience in remote hollows, while unions and critics targeted stores as symbols of corporate control.

At Carswell, the Houston and Koppers store was also where people encountered the modern world of manufactured goods and national advertising. Sanborn maps and NRHP documentation suggest a general store layout rather than a narrow counter. Customers could buy everything from flour and lamp oil to shoes and school supplies under the same high ceiling. The post office brought in letters from relatives who had moved away for work. Payday lines snaked through the same space where women compared fabric and parents bought treats for children.

Oral histories from McDowell County and photographs of similar Koppers stores in Wyoming County show broad steps and porches crowded on Saturdays, when miners settled accounts and families made their main weekly shopping trip. The Houston store’s long arcade and generous front lawn would have absorbed those crowds and left room for children to play under the eye of clerks and supervisors. Daily life at Koppers Store mixed necessity and community in ways that are hard to disentangle.

From coal economy to vacancy

As coal employment declined in the postwar decades, Carswell’s mines cut back and closed. By the 1960s the store’s original function had largely ended. Sources compiled by the Town of Kimball and public history entries indicate that the building housed a dairy operation, a construction firm, and later offices for McDowell County emergency services. Each new use altered the interior to some degree, but the exterior stayed remarkably intact.

By the end of the twentieth century, however, the store sat vacant for years. Coal Heritage surveyors noted that while many of McDowell County’s dozen or so surviving store buildings had already been demolished or were in ruin, the Houston store still stood with its brick walls, roofline, and basic floorplan intact. That combination of vacancy and integrity made it both vulnerable and valuable. It could have easily gone the way of other abandoned company properties. Instead, local residents chose a different path.

Restoration and the work of memory

In 1991 the Houston Coal Company Store joined the National Register of Historic Places as part of a multiple-property listing on coal company stores in McDowell County. The nomination emphasized its uncommon size, architectural quality, and high degree of preservation, describing it as perhaps the most intact example of its type in the county. That recognition later helped unlock grants and heritage funds.

Beginning around 2005, playwright and community leader Jean Battlo and a circle of partners began pressing for full restoration. A National Park Service evaluation of the National Coal Heritage Area notes that the Coal Heritage Highway Authority reserved $729,000 of its remaining earmarked federal funds specifically for restoration of the Houston Company Store. A West Virginia Humanities Council newsletter and local coverage later estimated total restoration costs at roughly $1.5 million, blending federal, state, and local sources.

Contractors repaired and cleaned the exterior brick, replaced windows and doors in keeping with the original fenestration pattern, restored the concrete terrace and steps, and reinstalled signage that recalled the Koppers era. The Town of Kimball’s summary points out that these major exterior updates were completed by spring 2016. Inside, local groups worked to adapt the big open floor to exhibits, events, and community gatherings without erasing the sense of the original store.

In her thesis on co-creative media and Appalachian counter-narratives, scholar Elon B. Justice highlights Battlo’s work at Houston Company Store alongside other preservation projects in McDowell County. She sees the restoration of the store into a museum as part of a broader effort by residents to reclaim spaces of extraction and turn them into places for telling their own stories. Service-learning projects coordinated through Concord University, planning assistance from West Virginia Brownfields, and programming supported by the National Coal Heritage Area have all treated the store as a laboratory for heritage tourism and community development rather than a static monument.

Today the building hosts museum exhibits, arts events, and seasonal attractions like the “Creepy Company Store” haunted experience, a reminder that even solemn places can be repurposed with humor and creativity. Where pay lines once stretched out the door, visitors now come to hear stories, watch performances, and imagine the camp that has largely vanished up the hollow.

Why Koppers Store still matters

In the early 1990s, a National Coal Heritage survey counted a small handful of significant surviving coal company stores in McDowell County. Some, like the Tidewater store, have since disappeared or fallen into deeper disrepair. Others have been altered so heavily that it is hard to see the original design. The Houston Coal Company Store at Carswell is now one of the best-preserved examples of its kind in the state and a rare place where visitors can still experience the scale and presence of a coalfield commissary in its original setting.

Its story also complicates simple narratives about company stores. The building was an instrument of corporate power and a node in an economic system that often left workers in debt. It stood within sight of a mine where explosions twice killed men underground. Yet it was also a post office, a neighborhood meeting place, and now a community museum directed by people who have lived with the long aftermath of coal.

Standing on the lawn and looking up Carswell Hollow, it is easy to imagine miners walking down at the end of a shift, families gathering on the steps on Saturday, and, decades later, volunteers scraping paint and scraping together grants so the building would not fall. The store’s arched windows and green roof no longer advertise the wealth of Houston or Koppers. Instead they frame a different message, one written by McDowell Countians who have chosen to keep this building as a place where Appalachian history can be told from the inside out.

Sources & Further Reading

Aurora Research Associates, LLC. Coal Heritage Survey Update Final Report, McDowell County, West Virginia. Charleston: West Virginia State Historic Preservation Office, November 15, 2018. https://npshistory.com/publications/nha/national-coal/survey.pdf NPS History

Chambers, S. Allen Jr. “Houston Coal Company Store and Houston House.” In SAH Archipedia. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press for the Society of Architectural Historians, 2013–. http://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/WV-01-MD8 SAH ARCHIPEDIA

“Carswell Mine Explosion.” United States Mine Rescue Association, Mine Disasters in the United States. https://usminedisasters.miningquiz.com/saxsewell/carswell.htm US Mine Disasters

Historical Marker Database. “Carswell Mining Complex.” HMdb.org. Accessed January 3, 2026. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=175929 US Mine Disasters

Historical Marker Database. “Houston Company Store.” HMdb.org. Accessed January 3, 2026. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=176970 US Mine Disasters

Justice, Elon B. Hillbilly Talkback: Co-Creation and Counter-Narrative in Appalachia. Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2021. https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/139417 DSpace

Marshall, Tina, Debra Rog, Abiola Ogunbiyi, and Johanna Dubsky. West Virginia National Coal Heritage Area Evaluation Findings. Rockville, MD: Westat, September 2012. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/heritageareas/upload/National-Coal-Evaluation-Findings-Report-Final.pdf National Park Service+1

Myers, Mark S. “McDowell County.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. Charleston: West Virginia Humanities Council, March 10, 2014. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1631 NPS History

National Archives and Records Administration. “Front of Company Store, Koppers Coal Division, Kopperston Mine, Kopperston, Wyoming County, West Virginia.” Photograph by Russell Lee, August 20, 1946. Still Picture Records Section. Digital image on Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Front_of_company_store._Koppers_Coal_Division,_Kopperston_Mine,_Kopperston,_Wyoming_County,_West_Virginia._-_NARA_-_540902.jpg Wikimedia Commons

National Coal Heritage Area Authority. “Houston Coal Company Store Celebration.” Event invitation, 2016. Norfolk and Western Historical Society. https://nwhs.org/mailinglist/2016/20160309_Houston_Store_invite.pdf

National Park Service. “West Virginia National Coal Heritage Area Evaluation Findings and DOI Letter to Congress.” Heritage Areas Evaluations. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/heritageareas/evaluations.htm National Park Service

Plowden, David. Kimball, West Virginia. Gelatin silver print, 1974. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth. https://emuseum.cartermuseum.org/objects/178780/kimball-west-virginia fanningfuneralhomes.com

Sanborn Map Company. Kimball, McDowell County, West Virginia, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map. New York: Sanborn Map Company, 1927. West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries. https://archives.lib.wvu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/2021 fanningfuneralhomes.com

Sanborn Map Company. Welch, West Virginia, Fire Insurance Maps, 1912, 1916, 1920, 1923, 1928, 1945. West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries. https://archives.lib.wvu.edu NPS History

Schust, Alex P. Billion Dollar Coalfield: West Virginia’s McDowell County and the Industrialization of America. Harwood, MD: Two Mule Publishing, 2010. https://npshistory.com/publications/nha/national-coal/survey.pdf NPS History

Schust, Alex P. Gary Hollow: A History of the Largest Coal Mining Operation in the World. Harwood, MD: Two Mule Publishing, 2005. https://npshistory.com/publications/nha/national-coal/survey.pdf NPS History

Sone, Stacy. “Coal Company Stores in McDowell County.” National Register of Historic Places, Multiple Property Documentation Form, c. 1990. West Virginia State Historic Preservation Office. http://www.wvculture.org/shpo/nr/pdf/cover/64500726.pdf NPS History

Sone, Stacy. “Houston Coal Company Store.” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. Washington, DC: National Park Service, December 16, 1991. West Virginia State Historic Preservation Office. https://wvculture.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Houston-coal-company-store.pdf West Virginia Culture Center+1

Steelhammer, Rick. “McDowell Coal Company Store Being Resurrected as Museum.” Charleston Gazette-Mail, March 25, 2015. https://www.wvgazettemail.com/news/mcdowell-coal-company-store-being-resurrected-as-museum/article_3e882bb8-1aeb-5fe9-96b9-83cd23aa1814.html Clio

Town of Kimball. “Houston Company Store.” Town of Kimball, West Virginia. Accessed January 3, 2026. https://kimball.wv.gov/visitors/Pages/Houston-Company-Store.aspx Kimball

U.S. Bureau of Mines. W. J. Pene and F. E. Griffith. Final Report, Explosion, Carswell Mine, Koppers Coal Company, Kimball, McDowell County, West Virginia, January 22, 1941. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines, 1941. https://usminedisasters.miningquiz.com/saxsewell/carswell_1941.pdf US Mine Disasters

U.S. Geological Survey. Welch, West Virginia, 7.5-Minute Series (Topographic). Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey, 1968. https://prd-tnm.s3.amazonaws.com/StagedProducts/Maps/HistoricalTopo/GeoTIFF/WV/WV_Welch_701594_1968_24000_geo.tif prd-tnm.s3.amazonaws.com

VT Special Collections and University Archives. “Koppers Store, Kimball, West Virginia.” Norfolk and Western Historical Photograph Collection, Norfolk Southern Collection of Materials Relating to the Norfolk and Western Railway Company, 1929. https://digitalsc.lib.vt.edu/items/show/36200 Digital Library at Virginia Tech

West Virginia Humanities Council. The West Virginia Encyclopedia. Charleston: West Virginia Humanities Council, 2006. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org NPS History

West Virginia Humanities Council. “Houston Coal Company Store.” West Virginia Humanities Council Newsletter (Fall 2015): 5. https://wvhumanities.org/forms/2015Fall.pdf West Virginia Humanities Council

West Virginia Humanities Council. “2015 Grant Awards.” Grant awards list, July 15, 2015. https://wvhumanities.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Grants_20150715.pdf West Virginia Humanities Council+1

“Writers’ Program of the Works Projects Administration in the State of West Virginia.” West Virginia: The Mountain State. 1941. Reprint, San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 2014. https://npshistory.com/publications/state_wv.htm NPS History

“Home / Houston Coal Company Store / Koppers Store.” The Clio: Your Guide to History. Accessed January 3, 2026. https://theclio.com/entry/44193 Clio

“Houston Coal Company Store.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Last modified 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Houston_Coal_Company_Store Digital Library at Virginia Tech

“Kimball, West Virginia.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Last modified 2024.

Author Note: Thank you to the Instagram account @appalachia_and_beyond for generously supplying the photographs for this piece. It is one of the prettiest company stores I have seen.