Repurposed Appalachia Series – Pauley Bridge of Pikeville, Kentucky

High above the green water of the Levisa Fork, a narrow one lane deck creaks and sways underfoot. Rough cut sandstone towers rise from each bank, their keystones carved with two simple lines: “W P A” and “1936.” For nearly a century, Pauley Bridge has carried coal camp residents, commuters, schoolchildren, and now tourists across the Big Sandy River at Pikeville, Kentucky.

Today it is a quiet pedestrian span and photo backdrop, but Pauley Bridge began life as a New Deal lifeline, one of the most distinctive Works Progress Administration projects in eastern Kentucky and the only swinging suspension bridge in the state to wear stone towers instead of steel.

Building a WPA lifeline (1935 to 1940)

In the mid 1930s, Pike County was still wrestling with the basic problem of getting across water. Roads followed the river and its tributaries, swinging back and forth from one bank to the other. Floods were frequent. Travel to the county seat could be slow or even impossible when the Levisa Fork ran high.

New Deal planners saw both a transportation problem and an employment opportunity. According to a Works Progress Administration index kept at the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Pauley Bridge was one of thirty seven wire suspension bridges proposed for construction in eastern Kentucky counties in 1936. Sixteen of those projects were later rescinded, but Pauley survived the cuts.

Design work fell to engineer O. S. Batten, and construction to WPA crews who drew federal pay while building infrastructure for their own communities. Work began in the later 1930s. By 1940 the new bridge stretched from the small unincorporated community of Pauley on the north bank to U.S. 23 and Pikeville’s growing road network on the south bank.

The National Register of Historic Places nomination describes the finished structure as a single lane suspension bridge with a 370 foot span over the river and an overall length of roughly 500 feet including its massive anchorages. The roadway is only about 10.8 feet wide, just enough for one vehicle. Wire rope main cables rise from concrete anchor blocks, pass over the tops of the stone towers, and drop again to the opposite bank. Round rod hangers loop around the main cables and bolt into steel floor beams that support wood stringers and a wood plank deck.

In an era when Pike County residents still remembered hauling freight on sleds instead of wagons, a permanent all weather crossing at Pauley was a revelation. The bridge gave miners, storekeepers, and schoolchildren a dependable link over the Levisa Fork into downtown Pikeville and onto the emerging modern highway system, tying a once isolated river settlement more tightly into the regional economy.

A rare swinging suspension bridge

From the start, Pauley Bridge was an unusual structure in Kentucky. A 1982 statewide survey of truss, suspension, and arch bridges identified only four vehicular swinging suspension bridges in eastern Kentucky that were still maintained by the state transportation department.

The National Register nomination goes further, noting that Pauley Bridge is the only swinging suspension bridge in the state, vehicular or pedestrian, with rough cut sandstone towers. Other WPA era swinging bridges at places like Tram in neighboring Floyd County used utilitarian steel I beam towers instead.

Those towers are a big part of the bridge’s visual power. Each is a paired stone pylon with an arched opening and a stepped parapet. The stones are laid in irregular courses, the joints deeply raked to emphasize the texture. Above the keystones, carved blocks carry the initials “W P A” on one side and the date “1936” on the other, a permanent signature of the agency that paid for the work.

Technically, Pauley is a “swinging” suspension bridge because it lacks the stiffening truss found on larger structures like the John A. Roebling Bridge over the Ohio River. Without that extra bracing, the deck ripples and sways under moving loads. The National Register documentation points out that this simplicity, combined with the efficient use of wire cables and timber, kept construction and transportation costs low, which was crucial for remote Appalachian counties with difficult terrain and limited budgets.

The WPA bridge program in eastern Kentucky did not just build Pauley. The agency planned dozens of small vehicular and pedestrian suspension bridges to knit rural hollows, mining camps, and county seats together. Yet even within that ambitious program Pauley stood out. A later New Deal context study prepared for the Kentucky Heritage Council highlighted Pauley Bridge as a representative WPA project and illustrated it with a Burgess and Niple photograph, underscoring both its engineering and its visual presence.

From lifeline to liability

For decades, Pauley Bridge carried everything from Model A Fords to coal trucks across the Levisa Fork. When it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992, it was still open to vehicular traffic and was one of only four swinging suspension bridges in eastern Kentucky still carrying vehicles.

By the 1970s and 1980s, though, the bridge was aging into a problem. Pikeville’s famed Cut Through project and associated road improvements shifted traffic patterns and encouraged heavier vehicles. City records from the late 1970s mention an emergency declaration after the “recent collapse” of the Pauley Bridge, a sign that at least part of the structure or its approaches had been damaged badly enough to alarm local officials.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, inspections grew more troubling. The wooden deck and stringers suffered from decades of weather, and the narrow roadway no longer met modern safety expectations. Heritage advocates pointed to Pauley’s uniqueness, but the city faced the very practical question of what to do with a swaying, historic one lane bridge on the edge of town.

The compromise solution arrived around the turn of the millennium. By 2000, the city closed Pauley Bridge to vehicular traffic. Within a year, all traffic ceased, and the span slumped into what one later observer described as the “appearance of an abandoned site.” Local photographs from the early 2000s show missing deck boards, vegetation growing between the planks, and rust on the cables and hardware.

It was during this period that some locals began calling Pauley a “bridge to nowhere.” Road realignments left the Pauley side less directly connected to major routes, and once the structure closed the phrase captured both its physical dead end and the fear that it might simply be removed.

Rehabilitation and a new purpose (2000s)

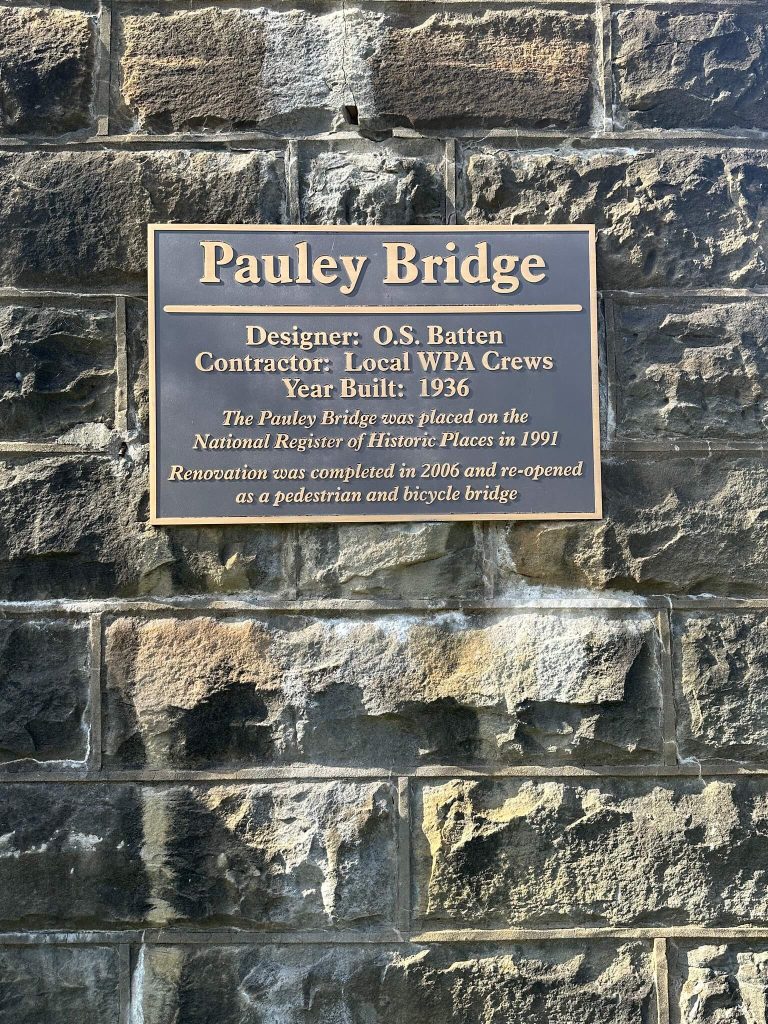

Rather than demolish the old bridge, Pikeville chose preservation. The city had a strong precedent. The 1991 National Register nomination already framed Pauley Bridge as a significant engineering work, and a growing statewide New Deal context emphasized the importance of WPA bridges as part of Kentucky’s twentieth century story.

In April 1993, a Pikeville board recommended that the city seek funds “to make the necessary repairs to reopen the Pauley Swinging Bridge,” signaling official interest in rehabilitation rather than removal. Over the next decade the city pursued federal Transportation Enhancement (TE) funding under the TEA 21 program. Minutes from the early 2000s document applications for enhancement grants specifically for Pauley Bridge repairs and later authorize the city to advertise for engineering proposals for a “Pauley Bridge Rehabilitation Project.”

By early 2006, the city awarded an engineering contract for the rehabilitation to Summit Engineering, Inc. HistoricBridges.org later recorded a rehabilitation date of 2006, matching local reports that Pikeville set aside restoration funds in 2004 and completed the work two years later.

The rehabilitation aimed to preserve Pauley’s character while making it safe for non motorized use. Summit’s plans retained the rough cut sandstone towers, concrete anchorages, and wire rope main cables that define the bridge, while replacing deteriorated timber decking and railings. The National Register file even includes an attachment prepared by Summit Engineering illustrating the bridge’s elevation and section after rehabilitation, evidence that preservation standards guided the work.

When the project wrapped up in 2006, Pauley Bridge reopened, not to cars and trucks, but to pedestrians and bicyclists. The narrow deck and swinging motion that had become liabilities for twenty first century traffic suddenly became assets for tourism and recreation.

A New Deal relic in a river town renaissance

Today Pauley Bridge is woven into Pikeville’s broader effort to reinterpret its riverfront and downtown. Pikeville’s comprehensive plan and tourism materials describe the span as a 380 foot WPA suspension bridge with rough hewn sandstone towers, highlighting it alongside historic commercial districts and the Hatfield McCoy feud sites as part of the city’s heritage inventory.

The Kentucky Wildlands National Heritage Area feasibility study lists Pauley Bridge as both a historic and recreational resource, describing it as a wooden pedestrian bridge over the Levisa Fork, built in 1936, with scenic views up and down the river valley. Regional writers and travel outlets have picked up the story, framing the bridge as one of Kentucky’s distinctive river crossings and a must see stop in Pike County.

Walkers who venture out onto the deck still feel the structure respond. The plank floor flexes slightly under each step, the wire cables singing in the wind, the gentle motion redistributing weight just as the engineers intended in the 1930s. The bridge is fixed in place by its stone towers and concrete anchorages, yet it remains a moving structure, literally and figuratively, connecting visitors to both the river below and the New Deal era above it.

Local tourism offices promote Pauley as a “serene view” of the Big Sandy, a favorite backdrop for family photos and engagement sessions. Social media posts and photography collections show it in fog, snow, autumn color, and spring flood, often with credit given to the Pike County Historical Society for historic images that document its original fabric and later restoration.

Why Pauley Bridge matters

Pauley Bridge is more than a local curiosity. It is a rare surviving example of a small scale WPA suspension bridge, a type once scattered across eastern Kentucky’s rivers and streams but now largely gone. It embodies the New Deal’s attempt to tackle both unemployment and infrastructure in the region, putting men to work on projects that would outlast them.

At the same time, Pauley’s later story mirrors the economic and environmental changes that reshaped Pikeville in the late twentieth century. Road realignments and megaprojects like the Cut Through changed how people moved along the Big Sandy. The old bridge went from lifeline to liability to cultural asset, preserved not because it was the most efficient way to cross the river, but because it had become part of the community’s identity.

Standing on the deck today, framed by sandstone towers that carry the initials of a long gone federal agency, visitors can read several layers of Appalachian history at once: the WPA’s promise of modernity, the coal era’s dependence on narrow mountain roads, the late twentieth century push for urban renewal, and the twenty first century shift toward heritage tourism and outdoor recreation. Pauley Bridge continues to swing above the Levisa Fork, connecting not only banks of a river, but decades of change in Pike County.

Sources & Further Reading

National Park Service. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Pauley Bridge, Pikeville, Pike County, Kentucky. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1991 (listed 1992). https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/53bc21d9-19ac-4d5a-97fe-937baa3ca142 NPGallery+1

Kentucky. Bureau of Highways. Division of Environmental Analysis. A Survey of Truss, Suspension, and Arch Bridges in Kentucky: For a Determination of Eligibility to the National Register of Historic Places. Frankfort: Kentucky Department of Transportation, Bureau of Highways, Division of Environmental Analysis, 1982. https://books.google.com/books/about/A_Survey_of_Truss_Suspension_and_Arch_Br.html?id=12sU0AEACAAJ Google Books+1

Fiegel, Kurt H. Report of the Archaeological Reconnaissance of the Pauley Bridge Relocation, Pike County, Kentucky. 1985. The Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR). https://core.tdar.org/document/142915/report-of-the-archaeological-reconnaissance-of-the-pauley-bridge-relocation-pike-county-kentucky core.tdar.org

City of Pikeville, Kentucky. “Regular Meeting, June 22, 1992.” Minutes of the Board of Commissioners. https://pikevilleky.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/1992_06_22.pdf City of Pikeville, KY+1

Kentucky Heritage Council and Kentucky Transportation Cabinet. The New Deal Builds: A Historic Context of the New Deal in East Kentucky, 1933–1943. Frankfort: Kentucky Heritage Council, 2013. https://heritage.ky.gov/Documents/NewDealBuilds.pdf Kentucky Heritage Council+1

National Park Service. Kentucky Wildlands National Heritage Area Feasibility Study. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, 2023. https://npshistory.com/publications/nha/kentucky-wildlands-nha-fs-2023.pdf NPS History+1

Powell, Helen C. Historic Themes for the Evaluation of Kentucky Highway Bridges, 1780–1940. Frankfort: Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, 1992. https://transportation.ky.gov/Archaeology/Documents/1992_Historic%20Themes%20for%20the%20Evaluation%20of%20KY%20Hwy%20Bridges%201780-1940.pdf Kentucky Transportation Cabinet+1

HistoricBridges.org. “Pauley Bridge.” HistoricBridges.org. https://historicbridges.org/bridges/browser/?bridgebrowser=kentucky/pauley/ Historic Bridges+1

Clio. “Pauley Bridge.” Clio: Your Guide to History. 2019. https://theclio.com/entry/83233 Clio+1

Pikeville–Pike County Tourism CVB. “Pauley Bridge.” TourPikeCounty.com. https://tourpikecounty.com/thingstodo/history_culture/pauley-bridge/ Tour Pike County+1

HMdb.org. “Pauley Bridge.” The Historical Marker Database. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=198614 HMDB

Carroll, Cornelius. “A Brief History of Pikeville, Pike County, Kentucky.” Welcome to Pikeville, Pike County, Kentucky. https://members.tripod.com/cornelius_carroll/Welcome/id24.htm Tripod+1

The Kaintuckeean. “NoD: Pikeville’s Pauley Bridge.” The Kaintuckeean (blog), August 31, 2011; updated August 20, 2019. https://www.kaintuckeean.com/pauley-bridge-pikeville/ The Kaintuckeean+1

Bridgehunter.com. “Pauley Bridge.” Bridgehunter.com. https://bridgehunter.com/ky/pike/42753 BridgeHunter+1

Tripadvisor. “Pauley Bridge.” Tripadvisor. https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attraction_Review-g39748-d11618863-Reviews-Pauley_Bridge-Pikeville_Kentucky.html Tripadvisor+1

Real Appalachia. “Pauley Bridge: Pikeville, Kentucky – Once Known as a ‘Bridge to Nowhere’, I Find Out What Is on the Other Side.” YouTube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4NJrgA-XDL8 YouTube+1

Explore The Kentucky Wildlands. “National Heritage Area.” The Kentucky Wildlands. https://www.explorekywildlands.com/kentucky-wildlands/national-heritage-area/ Kentucky Wildlands

Author Note: Writing about Pauley Bridge reminds me how much New Deal concrete, cable, and timber still quietly shape life in our river towns. I hope this piece helps you see a familiar photo spot as a worksite, a lifeline, and a testament to the people who fought to keep it swinging above the Levisa Fork.