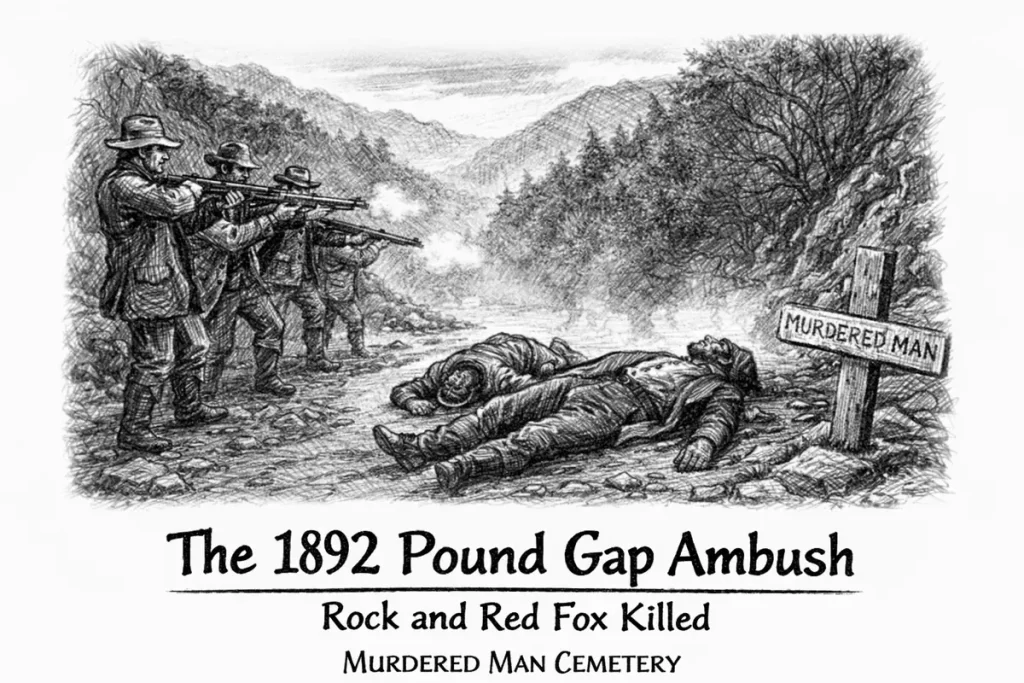

Appalachian History Series – The 1892 Pound Gap Ambush: Killing Rock, Red Fox, and a Cemetery Called Murdered Man

On the Kentucky–Virginia line above Jenkins and Pound, U.S. 23 squeezes through a blasted cut in Pine Mountain. A traveler who pulls off at the overlook today sees trucks grinding past and, a little way down the slope, a granite monument that reads “Pound Gap Massacre.” Another marker points toward a rock ledge along the old Fincastle Trail, “about 500 yards southeast of Pound Gap,” where five people were gunned down on May 14, 1892.

Local tradition calls the outcrop Killing Rock. The victims lie on a ridge nearby in a family burying ground once known as the Potter or Mullins Cemetery and now simply Murdered Man Cemetery.

For more than a century, the story of the ambush and the hanging that followed has been told in court records, local histories, dime novels, newspaper columns, and now websites and videos. What follows is an attempt to braid those voices together, leaning first on the surviving nineteenth century sources and the physical places that still anchor the story.

Moonshine, Feud Country, and “Bad Ira” Mullins

In the late nineteenth century Pound Gap was not only a state line but a traffic artery for timber, livestock, and liquor. The pass had been a route for surveyors and hunters since the days of Christopher Gist and Daniel Boone, and by the 1890s wagons and pack trains still threaded along the old road over Pine Mountain.

One of the men who moved through that landscape was Ira Mullins, born in Pike County, Kentucky, in 1857. Contemporary papers and later genealogists agreed that by the 1880s he had become a liquor dealer and small scale moonshiner who hauled whiskey between Kentucky, Virginia, and beyond. Some writers painted him with the nickname “Bad Ira,” describing him as both an illicit distiller and an informer who sometimes cooperated with federal revenue agents when it suited him. Those claims come not from official files but from later family histories and local writers, yet the newspapers that first reported his death clearly saw him as a known offender in the liquor trade. Virginia and West Virginia articles called him a “desperate moonshiner,” the sort of man whose killing they could frame as both shocking and grimly predictable.

By 1892 Ira had serious enemies. The specifics differ from source to source. Some accounts emphasize quarrels with fellow moonshiners over stolen whiskey, including the Fleming brothers, Cal and Henan. Others stress that he had turned informant against former partners. Most agree that in the months before the ambush someone had already tried to kill him once near Jenkins, an attack that left him partially paralyzed and dependent on a wagon for travel.

It was into that mix of moonshine, informers, and simmering grievance that Dr. Marshall Benton Taylor stepped. Taylor, known locally as Marsh or “Doc,” practiced as a country doctor and herb healer. He had once served as a United States marshal, and some later accounts insist that he also acted as a revenue agent or detective in the liquor wars, though clear documentation is thin. In the years after his death he would become better known by another name: the Red Fox of the Mountains.

A Wagon on the Old Fincastle Trail

Court days at Wise Courthouse drew people in from hollows and coal camps all over the county. Saturday, May 14, 1892, was one of those days. The party that left Pound that afternoon headed west toward Kentucky included seven people. Most of what we know about the group comes from early newspaper reports, the later indictment of Dr. Taylor, cemetery records, and one of the survivors’ testimony as preserved in later histories.

The wagon itself carried Ira Mullins; his wife, Louranza; his cousin or kinsman, Wilson Mullins; and hired hand John Chappell, sometimes listed as John Chappell Mullins. Walking nearby was another hired man, Greenberry Harris. Along with them traveled Ira’s teenage son, often identified as John Harrison or John Henry, and Ira’s sister, Jane Mullins, who was also Wilson’s wife.

The party had been in Wise to attend to both business and legal matters and was returning toward the Jenkins area along the mountain road. The route followed the old Fincastle Trail across the ridge, then wound down toward Kentucky. On the Virginia side, a rock outcrop leaned above a sharp bend. In later years the site would earn its new name, Killing Rock.

The Ambush at Killing Rock

Near that outcrop the team pulling the wagon suddenly pitched, and gunfire rolled down from the slope. Contemporary reports published in Richmond, Roanoke, Wheeling, and other cities agree that the first shots killed the mules or horses, stopping the wagon in the road. What followed was a short, concentrated burst of rifle fire into the trapped party.

Five people died either in the wagon or within a few yards of it: Ira Mullins himself; his wife, Louranza; Wilson Mullins; John Chappell; and Greenberry Harris. Jane Mullins survived by rolling over the bank and hiding in brush, wounded but alive. Ira’s teenage son escaped by running down the mountain, his overall strap reportedly shot through by a bullet as he fled. Both the survivors later told their version of the attack to authorities and neighbors, though their detailed testimony is preserved only indirectly in later histories and newspaper summaries.

Telegraph wires carried the news out of the mountains almost immediately. On May 17 the Richmond paper The State put the story on its front page, naming the dead as “Ira Mullins and wife and child, Wilson Mullins and John Chapel Moore” and describing the ambush as the work of “assassins” near Pound Gap. Papers as far away as Wheeling and West Georgia repeated the account, calling Mullins a notorious moonshiner and dwelling on the horror of an entire family murdered beside the road.

At first the gunmen were unknown. The suspicion that fell almost immediately on Doc Taylor and the Fleming brothers came from local rumor, the survivors’ statements, and the pattern of earlier threats. Within a short time, however, the story hardened. As one later Wise County summary put it, “Dr. M. B. Taylor, known as the Red Fox of the Mountains, together with Cal and Henan Fleming, were charged with the ambush of the Mullins party at Killing Rock.”

Manhunt on the Border

Once word of the massacre spread, law officers and posses from both sides of the line moved to hunt the suspects. Early dispatches reported Taylor captured and jailed at Wise on suspicion of complicity in the murders. By early August the Roanoke Times and local Wise County columns were reporting that a grand jury had indicted Marshall B. Taylor “for the murder of Ira Mullins and others near Pound Gap.”

The Fleming brothers proved harder to secure. Most versions agree that Cal and Henan fled deeper into the mountains and then toward West Virginia. In some twentieth century retellings Cal died in a shootout with officers there, while Henan was eventually arrested and brought back for trial, only to be acquitted. Those pieces of the story come mostly from later newspaper columns and local writers who relied on fading memory and scattered court records.

Through all of this, Taylor insisted that he was innocent. He did himself no favors with the way he proclaimed that innocence. Contemporary journalists and later retellings describe him quoting scripture, warning of divine judgment, and insisting that he would be vindicated beyond the grave. His sermons and jailhouse interviews helped fix his image as the Red Fox, a mountain preacher-physician who moved easily between pulpits, sickbeds, and the rougher edges of the law.

“Commonwealth v. M. B. Tayler”: Trial at Wise Courthouse

The case of Commonwealth versus M. B. Taylor came before the Wise County Court in 1892 and 1893. The original indictment survives in the county records, a four page document charging Taylor with the murder of Ira Mullins and the others near Pound Gap. A scanned copy, preserved through a cultural project at Appalshop’s Roadside Theater, remains one of the clearest official documents tying Taylor to the ambush.

During the trial the prosecution argued that Taylor and the Fleming brothers had set the ambush after months of threats and a failed earlier attempt. The state leaned on the survivors’ testimony, on witness statements about threats and movements before the attack, and on the larger pattern of violence around the liquor trade. The defense tried to cast doubt on identification and motive, and at one point Taylor’s lawyers raised questions about his sanity, hoping to avert the gallows.

The full transcript of the proceedings does not survive. Charles A. Johnson, a Wise County clerk who later wrote A Narrative History of Wise County, Virginia, recorded that a complete trial record had once been prepared for appeal but was lost. Much of what modern researchers know about the courtroom exchanges comes through Johnson’s book and from later writers who quoted sections of the vanished transcript while it was still accessible.

What we do know is the outcome. In late 1892 the jury found Taylor guilty of murder. Judge Samuel or Samuel W. Williams pronounced the death sentence. Execution was set for October 27, 1893, at Wise Courthouse. Newspapers from Georgia to the Atlantic coast took note of the case, fascinated by the blend of mountain feud, moonshine, and a defendant who preached his own funeral sermon.

Dynamite in the Graveyard

While Taylor’s lawyers worked on appeals, something happened up on the ridge where the victims lay. In August 1892 the Richmond Dispatch carried a story from Clintwood under the headline that Ira Mullins’s grave had been desecrated by dynamite. According to the correspondent, unknown persons had placed an explosive charge in Mullins’s grave, scattering his remains and damaging the coffin.

Out of state papers copied the report with lurid detail. An Ohio paper summarized the incident by reminding readers that a “desperate moonshiner” and his family had been murdered near Pound Gap and now even his grave had been blown open.

Why anyone would dynamite a grave is a question that has fed rumor ever since. Later family stories and local columns suggested that someone believed Ira had secreted money or valuables in the coffin, perhaps from his liquor dealings. Others thought the act was meant to make sure he stayed in the ground, a final insult in a violent feud. The newspapers of 1892 and the surviving court records do not name suspects, leaving the grave desecration one of the grimmest mysteries in the whole saga.

The place itself is not a mystery. The hillside burial ground above Jenkins became known as Murdered Man Cemetery, a name that appears in twentieth century local writings and that still clings to the site in modern articles and marker tours. Photographs of the stones for Ira, Louranza, Wilson, John Chappell, and Greenberry confirm their dates and link the names carved in marble to the headlines of 1892.

Hanging the Red Fox

On October 27, 1893, crowds gathered at Wise for the execution of Dr. Marshall Benton Taylor. One Georgia paper ran a long story on the event, describing Taylor’s life, the Pound Gap killings, and the final moments on the scaffold. It repeated the detail, also preserved in Wise County tradition, that Taylor dressed in a white suit for the hanging and asked for a white hood rather than a black one, explaining that white symbolized innocence and the garments he expected to wear in heaven.

At the appointed hour Taylor walked onto the gallows in the yard near the Wise County Courthouse. The building’s official history would later note that one of the most famous cases ever heard there was that of the Pound Gap Massacre and that its outcome ended with the execution of the man now known far beyond Wise as the Red Fox of the Mountains.

Taylor used his last opportunities to preach and to declare his innocence. Newspaper accounts describe him quoting scripture and warning the crowd that Christ would judge those who had wronged him. When the trap finally dropped, he joined a long list of men hanged under Virginia law, but his case lingered in print and memory longer than most.

In later years playwrights and storytellers would return to that moment. Roadside Theater’s script “Red Fox: Second Hangin’,” developed in the late twentieth century, stages the execution as a community memory piece, blending oral histories from Letcher and Wise counties with fragments of documented history.

Stories, Trails, and Markers

If the trial record was lost, the story of Pound Gap was not. In 1938 Charles A. Johnson devoted a full chapter of his Narrative History of Wise County, Virginia to the ambush, trial, and hanging. He had spent decades in the courthouse and drew on minute books, docket entries, and the now missing transcript. Later reference works and genealogy web pages lean heavily on Johnson’s account when they summarize the massacre.

Around the same time or soon after, novelist John Fox Jr. used the tale as inspiration for his Red Fox stories, placing a fictionalized version of Taylor in his broader world of Appalachian characters. He returned to the Wise hanging in essays and sketches, helping to spread the Red Fox image far beyond the counties that had actually known Marsh Taylor as a neighbor and doctor.

More recently locals and visitors have followed the story on foot. The Red Fox Trail in the Jefferson National Forest leads hikers from Pound Gap down toward the ambush site, passing interpretive signs that quote early descriptions of the killings and list the victims. At the gap itself, a stone historical marker erected in the late twentieth century summarizes the event and notes that “Doc Taylor was convicted and hung. Cal was shot and killed. Henan was acquitted.”

The cemetery on the Kentucky side, meanwhile, has become a regular stop on tours and storytelling conferences. Writers like Nancy Wright Bays and Joanna Sergent, along with projects such as Kentucky Tennessee Living and the Pound Historical Society, have documented the stones and told the story of how the old family plot came to be called Murdered Man Cemetery.

Online, the massacre has inspired everything from careful research blogs and collaborative genealogy pages to YouTube documentaries and ghost tours. The Wikitree “Space: The Pound Gap Massacre” page stitches together a detailed timeline with citations to Johnson, the Richmond Dispatch grave article, and other sources. AppalachianHistory.net has reprinted the 1893 Kentucky Explorer narrative that drew heavily on contemporary newspapers to narrate the ambush, hunt, and hanging. The site Kentucky Tennessee Living hosts a sprawling multi-part series that quotes dockets, family Bible records, and copied sections of the lost transcript, sometimes preserving details that would be hard to recover otherwise.

At the same time, those derivative sources have also propagated errors, exaggerations, and sometimes contradictory versions of events. Sorting the “official story” from elaboration requires going back, whenever possible, to the 1892–1893 newspapers, the surviving indictment, cemetery stones, and the minute books in Wise County.

Why the Pound Gap Ambush Still Matters

The 1892 ambush at Pound Gap is often listed as a feud killing or a moonshine massacre. It was both and more.

At one level the shooting at Killing Rock grew from personal grudges and the brutal economics of liquor in a dry or semi-dry region. Men like Ira Mullins, the Fleming brothers, and Marsh Taylor moved in a borderland where local loyalties, federal revenue laws, and private profit pulled in different directions. Violence was never far away.

At another level the story reveals how a single act of violence in a remote place became a national sensation. Within days newspapers from Richmond and Roanoke to Wheeling, Savannah, and small Midwestern towns carried versions of the ambush, describing it with the language of “desperadoes” and “massacre.” Those outside papers often got details wrong, but they show how the wider country imagined the Appalachian border as a place where moonshiners slaughtered families and preachers mounted the gallows in white linen.

For the communities along Pine Mountain the events at Pound Gap still live closer to the bone. Residents today can point to the rock, the cemetery, and the courthouse where the trial played out. Family descendants can trace their roots through the Mullins, Potter, Harris, and Fleming lines, arguing still over guilt and motive. Heritage groups and storytellers continue to wrestle with how to present the narrative honestly, honoring the dead without romanticizing the violence.

The markers at the gap and the stones at Murdered Man Cemetery offer their own kind of answer. They fix names, dates, and places in granite and marble, reminding visitors that behind every “massacre” headline were specific people riding home in a wagon on a May afternoon. In that sense the Pound Gap Ambush is not only a tale of a doctor called Red Fox or a moonshiner called Bad Ira. It is a border story about law and lawlessness, memory and forgetting, and the way a single bend in a mountain road can carry a century of history.

Sources & Further Reading

“Ira Mullins’ Grave Desecrated. Ghouls Dynamite the Remains.” Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA), August 18, 1892, p. 1. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.newspapers.com/article/richmond-dispatch-ira-mullins-grave-dese/8001892/

“Taylor, the Murderer of the Mullins Family.” The State (Richmond, VA), September 12, 1892, p. 1. Virginia Chronicle. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://virginiachronicle.com

“The Pound Gap Murders.” Wheeling Register (Wheeling, WV), May 17, 1892, p. 1. Virginia Chronicle. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://virginiachronicle.com

“Doc Taylor Indicted for Murder.” Roanoke Times (Roanoke, VA), August 4, 1892, p. 1. Virginia Chronicle. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://virginiachronicle.com

“Pound Gap Massacre.” Norfolk Landmark (Norfolk, VA), May 17, 1892, p. 1. Library of Virginia, Virginia Chronicle. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://virginiachronicle.com

“Pound Gap Murderers.” True Citizen (Waynesboro, GA), September 10, 1892, p. 1. Georgia Historic Newspapers. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu

“The Pound Gap Murderers.” The Washington Gazette (Washington, DC), July 28, 1892, p. 1. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov

“Red Fox Taylor Hanged at Wise.” The Morning News (Savannah, GA), October 28, 1893, p. 1. Georgia Historic Newspapers. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu

“Commonwealth vs. M. B. Tayler. Indictment for Murder.” Wise County Circuit Court (Virginia), 1892. Indictment scan hosted by Roadside Theater / Appalshop. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://archive.roadside.org/commonwealth-vs-m-b-tayler-indictment

“Dickenson County Newspaper Articles 1890–1900.” Transcriptions of local newspaper items, including references to the Pound Gap murders and M. B. Taylor’s indictment. USGenWeb Archives. Accessed December 28, 2025. http://files.usgwarchives.net/va/dickenson/newspapers

“Pound Gap Massacre.” Historical marker text, HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. Marker near Pound Gap, Letcher County, Kentucky / Wise County, Virginia. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=90801

“Pound Gap.” Historical marker text, HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. Marker near U.S. 23 at Pound Gap. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=97150

Virginia Department of Historic Resources. “Wise County Courthouse.” National Register of Historic Places nomination, notes on the Pound Massacre trial of Dr. M. B. Taylor. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/wise_county_courthouse_nomination.pdf

“Ira Mullins (1857–1892).” Memorial page. Find a Grave. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/16007729/ira-mullins

“John Wesley ‘Devil’ Wright (1844–1931).” Memorial page with Pound Gap Massacre note. Find a Grave. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/33609227/john_wesley-wright

Pound Gap Massacre ~ Killing Rock (geocache listing). “Mullins Massacre at Pound Gap near the Kentucky–Virginia Border – 1892.” OpenCaching US. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.opencaching.us/viewcache.php?wp=OU06A5

“Pound Gap.” ExploreKYHistory (Kentucky Historical Society), entry for Kentucky Historical Marker about Pound Gap’s transportation and Civil War significance. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://explorekyhistory.ky.gov/items/show/237

“Pound Gap of Pine Mountain.” Letcher County Tourism – Kentucky.gov. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://letchercounty.ky.gov/tour/Pages/attract.aspx

Chesnut, D. R., Jr., coord. “Geology of the Pound Gap Roadcut, Letcher County, Kentucky.” Guidebook for the 1998 Annual Field Conference of the Kentucky Society of Professional Geologists. Kentucky Geological Survey. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://kgs.uky.edu/kygeode/services/pubs/MoreInfo.asp?titleInput=228

“Appalachian Mts – Pound Gap.” SEPM Strata: Depositional Analogues. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.sepmstrata.org/page.aspx?pageid=433

Johnson, Charles A. A Narrative History of Wise County, Virginia. Norton, VA: Norton Press, 1938. Digital access via Gilliam Family of Virginia. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://gilliamsofvirginia.org/wisecountyhistory.html

Fox, John Jr. Blue-grass and Rhododendron: Out-doors in Old Kentucky. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901. Internet Archive edition. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://archive.org/details/bluegrassrhodode00foxjrich

Fox, John Jr. “The Red Fox of the Mountains.” In Blue-grass and Rhododendron: Out-doors in Old Kentucky, 1901. Reprinted online at Yeahpot.com. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://yeahpot.com/taylor/redfoxhanging.php

“Hangings at Gladeville.” Historical Sketches of Southwest Virginia. USGenWeb. Includes excerpts about the execution of Dr. Marshall Benton Taylor at Wise Courthouse. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://sites.rootsweb.com/~vahsswv/historicalsketches/hangings%20gladeville.html

“Wise County, Virginia.” Gilliam’s of Virginia (RootsWeb). Concise county sketch referencing the Pound Gap Massacre and Red Fox Taylor, citing Johnson’s Narrative History. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://gilliamsofvirginia.org/wisecounty.html

Baldwin, Doris Barber, and Oakley Dean Baldwin. Killing “Moonshine” Mullins: And the Aftermath. North Charleston, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://books.google.com/books?id=VBHNjwEACAAJ

Baldwin, Oakley Dean. The Killing Rock: Potter Family Connections. Independently published, 2019. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://books.google.com/books?id=n7W6wgEACAAJ

Tabler, Dave. “The Killing Rock Massacre of 1892.” AppalachianHistory.net, September 27, 2017. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.appalachianhistory.net/2017/09/the-killing-rock-massacre-of-1892.html

———. “All Who Remained Were Quickly Shot Dead (Part 2 of 2).” AppalachianHistory.net, September 28, 2017. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.appalachianhistory.net/2017/09/all-who-remained-were-quickly-shot-dead.html

“Pound Gap Massacre – Killing Rock.” Kentucky Tennessee Living. Multi-part series including “The Pound Gap Massacre,” “The Killing Rock,” and “Who Was Ira Mullins.” Accessed December 28, 2025. https://kytnliving.com/the-killing-rock-2/

“The West Virginia Shoot-Out: Killing Rock – The Untold Story Part 4.” Kentucky Tennessee Living. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://kytnliving.com/the-west-virginia-shoot-out-the-untold-story-part-4/

“Who Was Ira Mullins: Killing Rock – The Oft Told Tales Part 6.” Kentucky Tennessee Living. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://kytnliving.com/ira-mullins-killing-rock-the-oft-told-tales-part-6/

“The Killing Rock – Kentucky Tennessee Living.” Video and article series on the massacre and Murdered Man Cemetery. Kentucky Tennessee Living. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://kytnliving.com/the-killing-rock-2/

“Space: The Pound Gap Massacre.” WikiTree. Last modified February 11, 2025. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Space:The_Pound_Gap_Massacre

“Marshall Benton Taylor (1836–1893).” Profile of Doc Taylor. WikiTree. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Taylor-7248

“Pound Gap.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Entry on the gap’s geography and route history, including mention of the 1892 massacre and later exposures of the thrust fault. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pound_Gap

“Pound Gap (Wise County).” Civil War driving tour stop description. American Civil War in Southwest Virginia (Virginia Tech). Accessed December 28, 2025. https://civilwar.vt.edu/programs/drivingtour/poundgap.html

Doc M. B. Taylor – The Red Fox of the Mountains. Feature by Jadon Gibson. Troublesome Creek Times. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.troublesomecreektimes.com/articles/doc-m-b-taylor-the-red-fox-of-the-mountains/

“The Red Fox of the Mountains, Parts II–VIII.” Multi-part series by Jadon Gibson. The Mountain Eagle and partner papers, 2021–2025. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.themountaineagle.com

“Red Fox: Second Hangin’.” Play script. Roadside Theater / Appalshop, 1970s. Script PDF and project description. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://archive.roadside.org/red-fox-second-hangin

“Pound Gap – Historical Notes and Timeline.” Genealogical page compiling early route and settlement history for Pound Gap. Freepages Genealogy (RootsWeb). Accessed December 28, 2025. https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~dmohn/genealogy/poundgap.htm

“Black in Appalachia: Field Trip to Pound Gap and Leonard Woods Lynching Site.” Black in Appalachia field report PDF, 2022, with discussion of Pound Gap memorialization. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2499/may_22_record.pdf

Author Note: In writing this piece I leaned first on 1892–1893 newspaper coverage, surviving Wise County court records, and the graves and markers at Murdered Man Cemetery and Pound Gap. Because the full trial transcript is lost, some details come through later writers like Charles A. Johnson and modern syntheses, which I cross-checked wherever possible against primary documents. Any errors or interpretive choices are my own, and I welcome corrections or family stories that can help sharpen the record.