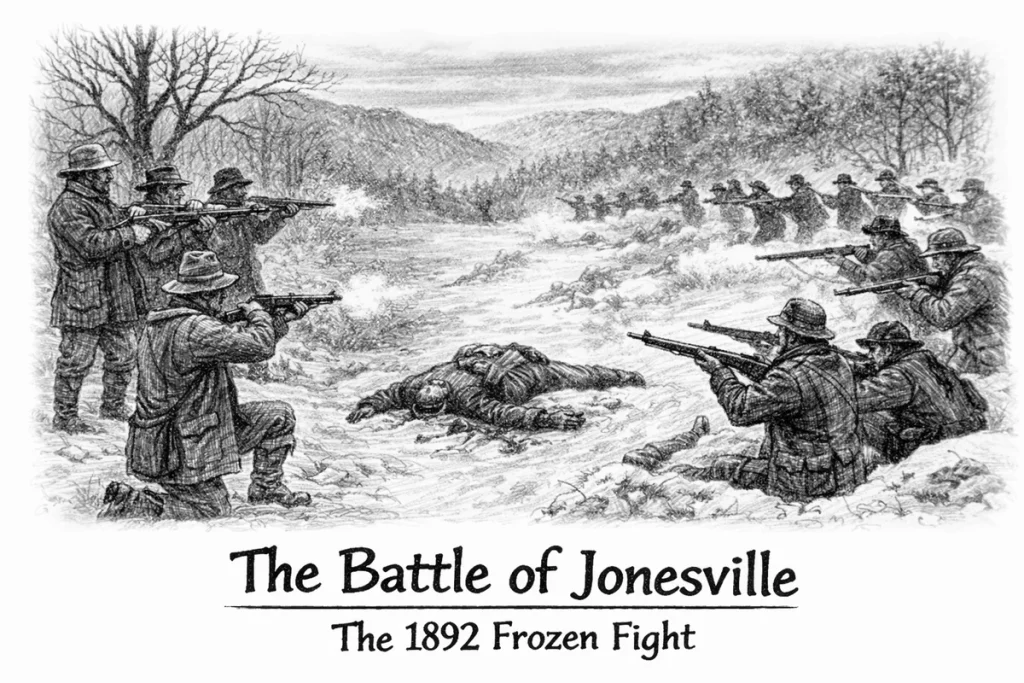

Appalachian History Series – The Battle of Jonesville: The Frozen Fight

On a bitter January morning in 1864, the war that had burned its way through Kentucky and East Tennessee finally reached Jonesville, the little seat of Lee County, Virginia. The town sits in Powell’s Valley along the old Wilderness Road route between Cumberland Gap and the Holston country. In most campaigns it barely appears at all, yet for one day it became the center of a hard fight between Union cavalry riding out from the Gap and Confederate troopers under Brigadier General William E. “Grumble” Jones.

Official reports, pension files, regimental histories, a nineteenth century prison memoir, and a National Register nomination for a brick farmhouse on the edge of town all tell pieces of the story. Together they reveal how Major Charles H. Beeres and men of the 16th Illinois Cavalry rode into Jonesville, how Confederate cavalry closed in from both east and west, and how hundreds of Union troopers ended their winter campaign not at Cumberland Gap but in Confederate prison camps, many at Andersonville.

The fight at Jonesville was small next to Gettysburg or Chickamauga. In the context of far Southwest Virginia, however, it was the largest single Civil War engagement, and it left its mark on the landscape in the form of a brick house, a cemetery of “unknown soldiers,” and stories that Lee Countians repeated for generations.

Jonesville, the Wilderness Road, and a contested valley

Long before soldiers in blue and gray rode through, Powell’s Valley carried travelers along the Wilderness Road between Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky. By the 1860s the same geography that guided wagon trains made Jonesville strategically important. The town lay on the road network that linked Cumberland Gap with the railroad and salt works farther east, and it sat near the junction of several gaps through Powell Mountain and Clinch Mountain.

For much of the war, Union and Confederate forces probed this corridor without large set-piece battles. Cumberland Gap changed hands more than once. In September 1863, Union troops captured the Gap and secured it for the remainder of the conflict, which forced Confederate commanders in Southwest Virginia to think in terms of raids rather than permanent occupation.

Jonesville itself saw earlier clashes. The National Register nomination for the Dickinson–Milbourn House notes skirmishes near the town in January and December 1863, as well as a Federal raid that burned the 64th Virginia’s camp that autumn. Men from Lee, Scott, Wise, and surrounding counties filled the ranks of the 64th Virginia Mounted Infantry, a local regiment with a troubled record that nonetheless played a key role in the 1864 fight.

By late 1863, the Union held the Gap with a relatively small force, while Confederates in East Tennessee and Southwest Virginia looked for a chance to strike. That opportunity seemed to come in the winter of 1863–64 when rumors spread that fewer than six hundred Union men guarded the Gap.

“Grumble” Jones plans a winter blow

Brigadier General William E. “Grumble” Jones, a Virginian familiar with the region, gathered a mixed mounted column for a midwinter thrust toward the Gap. According to the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies and Confederate reports, he marched from Little War Gap on Clinch Mountain on January 2, 1864, with somewhere around two thousand troopers.

Jones’s force included the 27th and 37th Virginia cavalry battalions, the 10th Kentucky Mounted Rifles, elements of the 8th Virginia Cavalry, and men of the reorganized 64th Virginia under Lieutenant Colonel Auburn L. Pridemore. Accounts tied to the 64th later remembered the march as brutal. One regimental summary notes that a soldier from the 64th Virginia froze to death in the saddle during the operation.

Jones’ intent was not simply to skirmish at Jonesville. His goal was Cumberland Gap itself. If he could brush aside the outlying Federal forces in Powell’s Valley, he hoped to sweep into the Gap before Union reinforcements could arrive.

A Union probe from Cumberland Gap

Union commanders at Cumberland Gap had their own worries. They had heard of Confederate activity in the valley and did not wish to be surprised. On January 1, 1864, Colonel Wilson C. Lemert ordered Major Charles H. Beeres of the 16th Illinois Cavalry to occupy Jonesville with a strong mounted detachment and a section of artillery.

The Illinois men were part of a regiment that had spent the war scouting and skirmishing across Tennessee, Kentucky, and western Virginia. State reports and regimental histories describe the 16th as a hard-used cavalry outfit that had been broken up into detachments along the border.

According to the Dickinson–Milbourn House nomination, Beeres rode into Jonesville with more than three hundred troopers of the 16th Illinois and three guns of the 22nd Ohio Battery. He drove a Confederate picket force from the eastern edge of the town and established his own positions there, while most of his men and the artillery camped near the Dickinson–Milbourn farm on the south side of what is now U.S. 58.

From the Union perspective, this looked like a bold but limited reconnaissance, a chance to feel out Confederate strength in the valley and perhaps disrupt local Confederate units like the 64th Virginia. The Federal detachment did not know that Jones’s larger mounted column was already on the move.

January 3, 1864: Surprise at dawn

Jones learned on January 2 that Union cavalry had taken possession of Jonesville. Rather than bypass the town, he decided to strike. He pushed his column across Powell Mountain overnight and approached from the southwest, while ordering Pridemore and the 64th Virginia to move in from the east.

Before dawn on January 3, Confederate cavalry descended on the Federal outposts at the eastern end of town. The National Register narrative, drawing directly on the Official Records, describes how Confederates overran the picket line, briefly captured the Union artillery, then lost the guns again when Beeres’s troopers rallied and fell back toward the shelter of the Dickinson–Milbourn buildings.

General Jones later reported that the Federals fought stubbornly, withdrawing toward the brick house and its outbuildings, where they made a stand with their guns covering the approaches. The Confederates pressed them, but Jones judged that storming the farm complex head on would cost more lives than he wanted to spend. Instead he chose to pin the Federals in place and wait for Pridemore’s column to arrive.

That decision turned the battle into a long, miserable day. Confederate troopers and Illinois cavalrymen exchanged fire across frozen fields and fence lines as temperatures stayed at or below freezing. Regimental histories for the 64th Virginia and later genealogical sketches speak of men with frostbitten feet and at least one trooper who never came out of the saddle alive.

Pridemore’s arrival and the closing of the trap

Late in the day, Colonel Auburn L. Pridemore and his portion of the 64th Virginia appeared from the east. With Jones to their west and Pridemore pushing from the opposite direction along the main road, the men of the 16th Illinois and their Ohio artillery found themselves caught between two Confederate lines.

Beeres pulled his command out of the buildings around the Dickinson–Milbourn House and tried to re-form on a hill just north of the farm, above a cornfield. From there his troopers could still cover the road with artillery fire, but the situation was untenable. Confederate reports and later summaries agree that the Illinoisans were heavily outnumbered, exhausted, and nearly surrounded as the winter light faded.

In his official report, Jones claimed that his men captured “383 officers and men, 45 of whom were wounded,” killed ten more, and took three pieces of artillery and twenty-seven six mule wagons. Modern regimental summaries repeat those figures and emphasize that Jonesville was the 64th Virginia’s most visible success, although it came at the cost of men lost to exposure and the fury of a winter march.

Whether or not the numbers are exact, there is no doubt that almost the entire Federal detachment was taken prisoner along with its guns. The Confederate victory temporarily cleared Powell’s Valley of Union cavalry and secured Lee County for the Confederacy for the remainder of the war.

The attack that never reached Cumberland Gap

For all its local importance, the battle at Jonesville never achieved Jones’s original aim. His intent had been to drive on Cumberland Gap, but the fight at Jonesville delayed his column and burned precious ammunition. The Dickinson–Milbourn nomination notes that Jones had to wait nearly two days for his own supply wagons to catch up, and by the time they arrived, word came that the Gap garrison had been reinforced.

The Confederates never again seriously attempted to retake Cumberland Gap. In that sense, the battle at Jonesville was both a striking tactical victory and a strategic dead end. Jones had captured hundreds of prisoners and valuable supplies in what soldiers later remembered as “The Frozen Fight,” but the mountain stronghold that had dominated so much planning in the region stayed in Union hands.

From Jonesville to Andersonville

For the captured men of the 16th Illinois Cavalry, the real ordeal began after the fighting stopped. A sixteen year old private named John McElroy of Company L was among those taken at Jonesville. Biographical sketches and his own later writing describe how he was marched first to Richmond and then to the new Confederate prison at Andersonville in Georgia, where he remained a prisoner for fifteen months.

McElroy’s 1879 memoir, Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Military Prisons, opens with his early service in the 16th Illinois and includes an account of the Powell’s Valley expedition, the surprise near Jonesville, and the columns of prisoners trudging south through the winter landscape. He does not devote many pages to tactical details, but his narrative helps us understand what capture meant for the ordinary cavalrymen whose names appear in the Official Records only as numbers.

Illinois state rosters and the regimental records of the 16th Illinois Cavalry list men who were “captured at Jonesville, Va., Jan. 3, 1864” and then died in prison or came home years later carrying the physical and emotional scars of imprisonment. The Congressional Serial Set preserves pension and claim files from men such as N. R. Gruelle of Company L, who had to prove that he had been taken prisoner at Jonesville in order to secure postwar benefits.

Powell’s Valley and the ridge above the Dickinson–Milbourn farm saw only one day of major fighting. For McElroy and hundreds of other Illinois troopers, the brief “action at Jonesville” marked the start of a much longer ordeal.

The Dickinson–Milbourn House and a battlefield beneath a farm

No official battlefield park protects the Jonesville site today, but the landscape still bears clear traces of the fight. On the western edge of town, the Dickinson–Milbourn House stands on a hill above U.S. 58. The 1840s brick dwelling, now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was already a prosperous farm when the armies arrived.

The National Register documentation ties the house directly to the battle. It states that much of the fighting on January 3 took place on the farm, and that Union troops used the house and its outbuildings as cover during the Confederate assault. The account of the battle in that nomination is explicitly based on the Official Records, and it describes Beeres’s men camping near the house, falling back into its yard and dependencies under pressure, then retreating to the hill north of the farm when Pridemore’s column swept through town.

Local tradition holds that the house served as a hospital after the battle, a claim that fits well with its position on the field and the common practice of using nearby farm dwellings as makeshift hospitals. The property’s later history contains its own example of how battle stories can twist in memory. A romantic local tale asserts that Union officer Henry Clay Joslyn, supposedly wounded and captured at Jonesville, recovered in the house and fell in love with his future wife Sarah Milbourn there. Archival work cited in the National Register nomination shows that Joslyn actually served in the 29th Massachusetts, fought at Petersburg rather than Jonesville, and met Sarah under different circumstances

In that sense, the Dickinson–Milbourn House is both a battlefield landmark and a lesson in how Civil War memory blends fact, family pride, and community storytelling.

“Unknown Soldiers” and Lee County memory

If the Dickinson–Milbourn House anchors the physical story of the battle, the cemetery west of town anchors the story of how Jonesville chose to remember it. Along U.S. 58 on the west side of Jonesville stands a monument in a small burial ground often known as the “Lee Cemetery of the Unknown Soldiers.” A tall marker and an accompanying sign commemorate Confederate soldiers who died in the battle and whose individual names were lost.

The Virginia Center for Civil War Studies notes that this is Lee County’s only Confederate monument and that it is dedicated not to a general or a cause in the abstract, but to unknown men who fell at Jonesville. Cemetery transcriptions and genealogical sites document the inscriptions and sometimes link them with family stories about relatives who were killed there or who helped bury the dead.

On the Union side, a family history of a man named James Washington preserves a story of the battlefield and nearby graves of “unknown soldiers” near Jonesville, told by descendants who knew only that he had been wounded there. These fragments mirror the official records in scale but not in detail. Where Jones counted “383 officers and men,” local memory reduces the fight to frozen bodies on a hill and nameless graves on the edge of town.

In the 2020s, Lee County organizations, including the Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society and local economic development groups, have worked with state agencies and the Civil War Trails program to improve interpretation at Jonesville. The Virginia Center’s driving tour guide gives directions to the cemetery, notes the nearby markers, and encourages visitors to think about how this relatively small battle shaped the wider struggle for control of Southwest Virginia.

Why the Battle of Jonesville still matters

On paper the Battle of Jonesville looks like countless other engagements summarized in the Official Records. A Confederate cavalry commander struck an isolated Federal force, inflicted a sharp defeat, then withdrew before achieving his larger objective. Yet the details uncovered in regimental rosters, pension files, local histories, and property nominations show why this particular fight still matters.

First, Jonesville illustrates how geography shaped the Civil War in Appalachia. The fight took place not because either side cared about the town itself, but because it sat on the road between the Holston valley and the Union stronghold at Cumberland Gap. The ridges and narrow valley floors dictated where men could march, camp, and form lines of battle.

Second, it shows the cost of small actions in the border counties. In a single winter day, a regiment like the 16th Illinois Cavalry could see hundreds of its men captured and scattered through the South’s prison system. The human consequences for those men, their families, and the communities they came from far outweighed the few lines they occupy in official reports.

Third, Jonesville highlights the complicated role of local Confederate units such as the 64th Virginia. Often criticized for poor discipline and internal disputes, they nonetheless delivered an important victory on their home ground, at a terrible physical cost to themselves.

Finally, the physical remains of the battle in Jonesville remind us that Civil War memory is layered. The Dickinson–Milbourn House carries not only the scars of battle but also stories that later generations told about who met and married there. The cemetery of unknown soldiers stands at the edge of town as both a graveyard and a monument, while new markers and driving tours encourage visitors to see the battlefield hidden under modern roads and school grounds.

For Appalachian historians, the Battle of Jonesville offers a case study in how a “small” engagement can illuminate the larger war in the mountains. It links the Wilderness Road to Andersonville, ties a brick farmhouse and a cemetery to decisions made in distant headquarters, and shows how, on one frozen day in January 1864, a quiet valley in Lee County briefly became the center of the Civil War world for the men who fought there.

Sources & Further Reading

United States War Department. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. 32, Pt. 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1891. Available via HathiTrust Digital Library. https://www.hathitrust.org

United States War Department. Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1891–95. Available via the Library of Congress digital collections. https://www.loc.gov

Adjutant General’s Office, State of Illinois. Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois. Vol. 8. Springfield: Phillips Bros., 1901. Digitized via Internet Archive. https://archive.org

“Thielman’s (16th) Illinois Cavalry Regiment History.” Illinois Civil War Regimental Histories, IllinoisGenWeb Project. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.illinoisgenweb.org

National Park Service. “Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System.” Database of Union and Confederate soldiers and units. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm

“Bradley Greenwall.” Memorial entry, Find a Grave. Notes capture at Jonesville, Virginia, 3 January 1864. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.findagrave.com

United States Congress. Letter from the Secretary of War, in the Case of N. R. Gruelle. U.S. Congressional Serial Set. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 19th century. Digitized via GovInfo. https://www.govinfo.gov

“Recent Fight in Lee County, Va.” Richmond Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), January 8, 1864. Available in the “Richmond Daily Dispatch 1860–1865” digital archive, University of Richmond. https://dispatch.richmond.edu

Anderson, J. C. “The Recent Fight in Lee County, Va.” The Confederate Union (Milledgeville, GA), February 16, 1864. Reprinted from the Bristol Gazette. Digitized in Georgia Historic Newspapers. https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu

[Runs of] Bristol Gazette and Abingdon Virginian (Southwest Virginia papers), January–February 1864. Contemporary coverage of the “recent fight in Lee County, Va.” Accessible via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov

McElroy, John. Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Military Prisons. Toledo, OH: D. R. Locke, 1879. Full text via Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org

“James Washington Civil War Stories.” Smith-Cernik Family History site. Family narratives describing wounding at the Battle of Jonesville and the “unknown soldiers” graves near Lee Cemetery. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://sites.rootsweb.com

Edwards, David A., and John S. Salmon. “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Dickinson–Milbourn House.” Richmond: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 1993. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/245-0004_Dickinson-Milbourn_House_1993_Final_Nomination.pdf

Virginia Department of Historic Resources. “Dickinson–Milbourn House.” Virginia Landmarks Register entry, 245-0004. Accessed July 2024. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/historic-registers/245-0004/

“Dickinson–Milbourn House.” National Register of Historic Places in Lee County, Virginia category, Wikimedia Commons. Includes NRHP reference number and photography. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:National_Register_of_Historic_Places_in_Lee_County,_Virginia

“Jonesville.” Historical Marker Database entry (Civil War Trails marker and context for the town and battle). Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=36028

Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Virginia Landmarks Register & National Register of Historic Places Master List. Richmond: DHR, updated 2018. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/pdf_files/RegisterMasterList.pdf

VCEDA (Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority). “VCEDA Approves Funds for Lee County Battlefield Tourism Project.” News release, May 23, 2025. https://vceda.us/vceda-approves-funds-for-lee-county-battlefield-tourism-project/

Krakow, Jere L. Location of the Wilderness Road at Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1987. https://npshistory.com/publications/cuga/location-wilderness-rd.pdf

“Tennessee Civil War GIS Project.” State of Tennessee, TNMap. Interactive mapping of battles and engagements, including Powell’s Valley and related operations. https://tnmap.tn.gov/civilwar/

United States Army Corps of Engineers. “Topographic Map of Powell River Valley … 1924.” Powell River Valley plane-table survey map (showing the Jonesville / Powell’s Valley corridor). https://usace.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16021coll10/id/10860/

Hubbard, David A., Jr., and Marion O. Smith. “The Rediscovery of Heiskell Cave: A Confederate Nitre Bureau Works.” Journal of Spelean History. National Speleological Society. https://caves.org/wp-content/uploads/Publications/journal-of-spelean-history/118.pdf

Hubbard, David A., Jr., and Marion O. Smith. Abstract, “The Rediscovery of Heiskell Cave: A Confederate Nitre Bureau Works.” Journal of Cave and Karst Studies 62 (2000): index. https://legacy.caves.org/pub/journal/PDF/V62/cave_62-03-fullr.pdf

Weaver, Jeffrey C. 64th Virginia Infantry. Virginia Regimental Histories Series. Lynchburg, VA: H. E. Howard, 1992. https://books.google.com/books/about/64th_Virginia_Infantry.html?id=SsAdAQAAMAAJ

“64th Virginia Infantry Regiment.” Civil War in the East. Modern regimental summary with service timeline and battle notes (including Jonesville). Accessed December 28, 2025. https://civilwarintheeast.com

“64th Regiment, Virginia Mounted Infantry – Confederate.” FamilySearch Research Wiki. Overview of organization, service, and sources for the regiment. https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/64th_Regiment%2C_Virginia_Mounted_Infantry_-_Confederate

“64th Virginia Infantry Roster.” USGenWeb Archives. Transcription of Confederate rosters with notes on Jonesville-era service. https://files.usgwarchives.net/va/military/civilwar/rosters/va64th.txt

“64th Virginia Mounted Infantry Regiment.” Wikipedia. Overview article on the regiment, with discussion of Jones’s court-martial of Col. Campbell Slemp and the unit’s service in southwest Virginia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/64th_Virginia_Mounted_Infantry_Regiment

“64th Virginia Infantry.” Virginia Regimental Histories Series listings, Baines Books. Brief bibliographic note on Weaver’s volume. https://bainesbooks.com/varegsrs/

Virginia Center for Civil War Studies (Virginia Tech). “Battle of Jonesville.” Civil War Driving Tour of Southwest Virginia. https://civilwar.vt.edu/programs/drivingtour/battleofjonesville.html

Virginia Center for Civil War Studies (Virginia Tech). “Civil War Driving Tour of Southwest Virginia.” Site overview, including Jonesville and related sites such as Cumberland Gap and Saltville. https://civilwar.vt.edu/driving-tour/

Virginia Center for Civil War Studies (Virginia Tech). “Confederate Monuments.” Includes entry for the Jonesville monument to unknown Confederate soldiers killed in the battle. https://civilwar.vt.edu/programs/drivingtour/confederatemonuments.html

Mize, Martha Grace. “History and Heritage Made Accessible: The Lee County, Virginia Story.” Honors thesis, University of Mississippi, 2017. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/641

Mize, Martha Grace Lowry. “Civil War in Southwestern Virginia.” The Lee County Story. https://www.theleecountystory.com/civil-war-in-southwestern-virginia/

Mize, Martha Grace Lowry. The Lee County Story. Multi-chapter online narrative history of Lee County. https://www.theleecountystory.com

“My Long Hunters” (R. W. Duncan, ed.). “The Battle of Jonesville – 1864.” Local-history and genealogy article synthesizing OR, regimental histories, and Lee County family traditions about the battle. https://www.mylonghunters.info

“My Long Hunters.” “64th Virginia Mounted Infantry Regiment” and related Lee County Civil War posts. Genealogical reconstructions of local soldiers and units, including the 64th Virginia and Jonesville casualties. https://www.mylonghunters.info/category/local-history

Spelean History / National Speleological Society. Articles and abstracts on Heiskell Cave (Jones Saltpeter Cave) and Lee County’s Confederate nitre operations, including “The Rediscovery of Heiskell Cave” (Hubbard and Smith). https://caves.org/wp-content/uploads/Publications/journal-of-spelean-history/113.pdf

National Park Service. “Cumberland Gap National Historical Park: Geodiversity Atlas.” Explains the strategic geography of Cumberland Gap and the Wilderness Road, including Civil War occupation. https://www.nps.gov/articles/nps-geodiversity-atlas-cumberland-gap-national-historical-park-kentucky-tennessee-and-virginia.htm

TNMap / Tennessee State Library and Archives. “Tennessee Civil War GIS Project – User’s Guide.” Documentation for the interactive GIS that maps Civil War engagements, roads, and terrain across Tennessee and Powell’s Valley. https://tnmap.tn.gov/civilwar/GIS%20User%27s%20Guide.pdf

McKnight, Brian D. Contested Borderland: The Civil War in Appalachian Kentucky and Tennessee. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2006. Publisher information. https://www.kentuckypress.com

Author Note: This piece grew out of my fascination with how a “small” mountain fight like Jonesville could send hundreds of men from a frozen Virginia cornfield all the way to Andersonville. I wanted to braid together the dry precision of the Official Records, the lived voices of prisoners and families, and the way Lee County has chosen to remember its unknown dead on a hillside cemetery and at the Dickinson–Milbourn farm. My hope is that readers come away seeing Powell’s Valley not as a footnote, but as part of the central story of how the Civil War was fought and felt in Appalachia.

During the battle of Jonesville, VA my gr gr grandfather 2nd Lt Samuel Osgood was killed and

he had two sons Charles and Samuel that were captured by confederate forces. One died at Andersonville and the other escaped and returned home.