Appalachian History

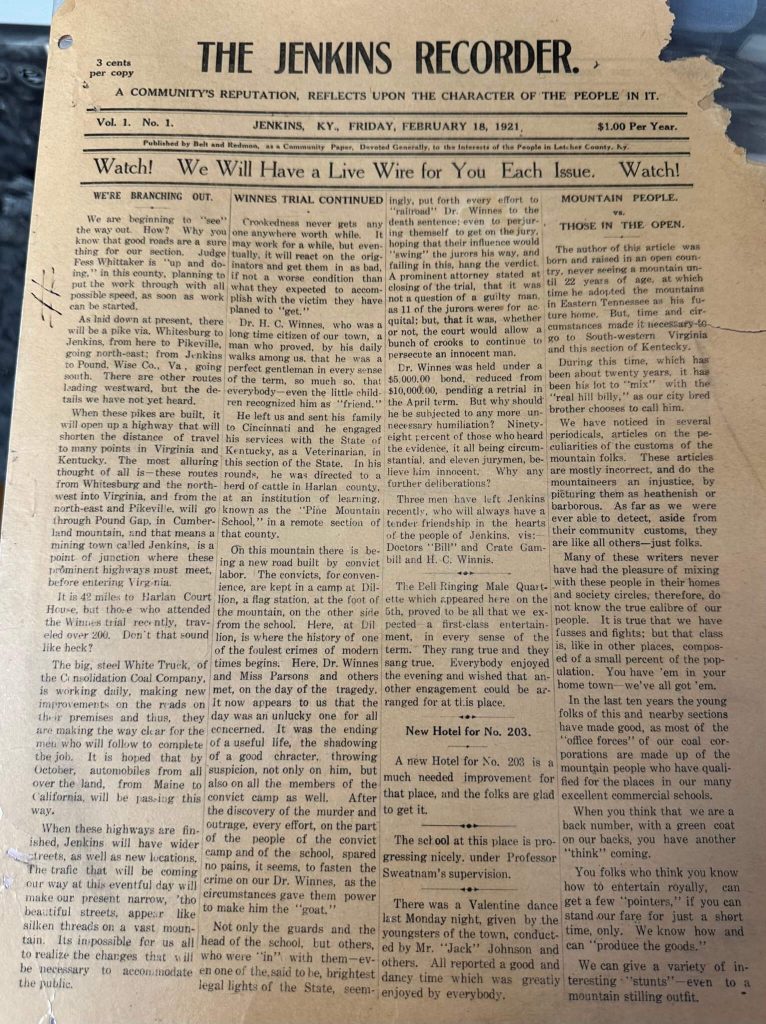

On winter mornings in the early 1920s, coal dust hung over Jenkins, Kentucky, while miners and store clerks climbed the steps of the big recreational building to buy their paper. Upstairs, on the second floor of that four story complex, a tiny shop ran the town’s one newspaper, the Jenkins Recorder. From that cramped room came church notes, company-town advertisements, and in its very first editorial a blunt rejection of the revived Ku Klux Klan.

Today only a slim run of this “little Jenkins Recorder” survives, but the traces it left tell an outsized story about coal camp life, racial politics, and the ways small town papers are rediscovered a century later through archives and online tools.

A coal company town in need of a voice

Jenkins was not a courthouse town that slowly grew around a public square. It was a coal company project. Consolidation Coal laid out the community in the early 1910s, after buying tens of thousands of acres in the Elkhorn coalfield. The town was incorporated in 1912 and quickly became the company built hub for satellite camps like Burdine and Dunham, stretching for miles along Elkhorn Creek.

Company engineers built more than tipples and tracks. They created a model town meant to impress investors and politicians, complete with hospital, hotel, school, clubhouse, and a large “Mayo Recreational Building” that opened in 1913. Photographs from the Consolidation Coal Company collection show that complex filled with bowling lanes, a soda fountain, and shelves of magazines and goods for sale.

The coal camp grew fast. Longtime resident Ransom Jordan later estimated that in the 1920s Jenkins alone held six or seven thousand people, not counting the neighboring camps. The town drew white mountaineers, Black railroad workers turned miners, and immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, all packed into a narrow valley controlled by a single company. It was the kind of place where a local newspaper could bind people together yet also pick fights with powerful forces.

Upstairs in the Mayo building

In a 1973 oral history, Jordan walked interviewers through the Mayo building floor by floor. The basement held a printing office. The upper stories housed a hotel, dentist office, and public library. On the second floor, he recalled, “The Jenkins Recorder was upstairs at one time… Belt was the man who run it… He did all the printing for the theaters.”

Those theaters were no small thing. Jordan remembered five movie houses in the company town and nearby camps, with a woman playing piano to accompany the silent films. The job printing done by Belt and his press kept handbills, tickets, and programs flowing alongside the weekly newspaper.

Jordan’s recollection fixes the Recorder in a very specific physical world: a coal company recreation palace where workers came to shower after their shift, bowl a few frames, buy a newspaper, and walk downstairs to catch a show. The paper was not separate from that company town universe. It lived right in the middle of it.

Piecing together a short run newspaper

For a long time, historians and genealogists knew almost nothing concrete about the Jenkins Recorder beyond scattered memories. That changed as state newspaper programs and digitization projects pulled together catalog data and microfilm holdings.

Reference tools built from the Library of Congress’s “Directory of U.S. Newspapers in American Libraries” list only one historical newspaper for Jenkins: the Jenkins Recorder, with a start year of 1921 and an uncertain end year marked simply as “19??.” That entry points researchers to a catalog card and to holdings records under LCCN SN89058394 and OCLC 19451497, which show which libraries have paper or microfilm copies.

Genealogy guides give a more precise snapshot. LDSGenealogy’s pages for Letcher County and for Jenkins list “Jenkins Recorder 1921-1922” with digitized images hosted at Newspapers.com. Newspapers.com itself describes the Jenkins Recorder archive as 128 searchable pages from 1921 and 1922, rich with birth, marriage, and obituary notices.

A 2019 “Way We Were” column in the Mountain Eagle in nearby Whitesburg, summarizing older clippings, likewise identifies the Jenkins Recorder as a local newspaper published in Jenkins in 1921 and 1922. A later 2022 column reprints a snippet noting that “The Jenkins Recorder newspaper has resumed publication after a few weeks of being dark,” a reminder that even a tiny paper could miss issues and restart in fits and starts.

Put together, these sources show a small town paper that certainly operated in 1921 and 1922, and that may have continued beyond those dates in issues preserved only on microfilm or scattered in local collections.

A paper of record for a young town

Even in its short run, the Jenkins Recorder functioned as something close to a newspaper of record for the company town. On April 21, 1921, the Carlisle Mercury, a weekly from central Kentucky, ran a legal notice that specified certain proceedings were to be “published in the Jenkins Recorder,” proof that courts and officials already treated the new title as a suitable place for public announcements.

For residents, the paper filled more personal needs. The surviving run on Newspapers.com includes the usual life markers so prized by genealogists: engagement notices, society tidbits, lodge news, store ads, and obituaries that pin down dates, kin networks, and coal camp addresses that otherwise vanish from the record.

Jordan’s interview hints at how those issues moved through town. He remembered the Mayo building as a hub where “everyone would come in and buy their newspaper,” part of a daily ritual that mixed company script, recreation, and news.

The little paper that took on the Ku Klux Klan

The Jenkins Recorder was not just a shopper and gossip sheet. In a study of Appalachian coverage of lynching, historian Alexander S. Leidholdt singles out the Recorder’s launch for special attention. He notes that the very first editorial in the inaugural 1921 issue of what he calls the “little Jenkins Recorder” directly repudiated the newly revived Ku Klux Klan.

Leidholdt identifies that piece as running in the 18 February 1921 issue. The editorial, as he describes it, rejected mob violence and secret vigilante organizations as threats to law, order, and civilized society. It is a remarkable stance for a start up paper in a coal company town in the early 1920s, when the Klan was surging across much of the South and had supporters in law enforcement and local government.

Jenkins’s own demographics help explain the courage and the stakes. The town’s coal boom brought in Black miners and railroad workers to live and work alongside white mountaineers and new immigrants, even as surrounding counties remained overwhelmingly white and deeply violent. In that setting, an editorial line that insisted on due process and denounced hooded vigilantism was not abstract moralizing. It was a plea for some measure of safety in a boomtown on edge.

From early warning to tragic confirmation

The Recorder’s anti Klan stance reads even more strikingly in light of what happened a few years later. In November 1927, Leonard Woods, a Black coal miner from Jenkins, was taken from the Letcher County jail by a white mob, carried up the new U.S. 23 highway to Pound Gap on the Virginia line, and there hanged, shot, and burned.

National coverage followed. The New York Times pushed the story under the headline “Negro Is Lynched as Kentucky Killer,” summarizing how Woods had been seized from jail, transported into Virginia, killed, and his body burned. Black newspapers and anti lynching advocates nationwide picked up the case, and Virginia responded in 1928 by passing the first state law in the country that explicitly defined lynching as murder.

Whether the Jenkins Recorder was still appearing in 1927 is not yet clear. The catalog record hints at a longer run than the 1921-1922 issues now digitized, but surviving copies have not been fully traced. What is certain is that editors in nearby towns, such as Bruce Crawford of Crawford’s Weekly in Norton, Virginia, took up the story and denounced the lynching in vigorous editorials that Leidholdt sees as part of the same Appalachian anti lynching tradition that the Recorder’s first editorial represented.

In that light, the Jenkins Recorder looks less like an isolated curiosity and more like an early voice in a regional press conversation about racial violence, law, and justice.

Why the Jenkins Recorder still matters

The Jenkins Recorder’s surviving issues cover only a short span, yet they preserve a rare look at a company town speaking in its own voice. They capture the ordinary details of life in a boom era coal camp, record the names and addresses of families who might otherwise slip from the written record, and remind us that even a tiny local weekly could confront the most dangerous forces of its day.

In a region often caricatured as backward or silent, the Recorder’s first editorial stance against the Ku Klux Klan, and its role in a broader conversation about lynching and the rule of law, show something different: an Appalachian coal town wrestling in print with what kind of community it wanted to be.

Sources & further reading

Jenkins Recorder archive, 1921-1922, Newspapers.com. Newspapers

LDSGenealogy, “Letcher County, Kentucky: Newspapers and Obituaries” and “Jenkins, Kentucky.” LDS Genealogy+1

RoadsideThoughts, “Jenkins (Letcher County, KY) – Local Newspapers” and related entry listing years of publication, LCCN, and OCLC for the Jenkins Recorder. RoadsideThoughts+1

Library of Congress, “Directory of U.S. Newspapers in American Libraries: About this collection.” The Library of Congress+1

Ransom Jordan, “Interview with Ransom Jordan,” in The History of Jenkins, Kentucky (1973), online edition. Penelope +1

“The Way We Were” columns, Mountain Eagle (Whitesburg, Ky.), July 10 2019 and June 15 2022. The Mountain Eagle+2The Mountain Eagle+2

Carlisle Mercury (Carlisle, Ky.), April 21 1921, legal notice specifying publication in the Jenkins Recorder. Nicholas County Schools+1

Alexander S. Leidholdt, “ ‘Never Thot This Could Happen in the South!’: The Anti-Lynching Advocacy of Appalachian Newspaper Editor Bruce Crawford,” Appalachian Journal 38 (2011), esp. discussion of the Jenkins Recorder’s inaugural editorial. JSTOR+1

“Lynching of Leonard Woods,” Wikipedia; Virginia Department of Historic Resources, “State Historical Marker ‘Leonard Woods Lynched’ to be Dedicated in Wise County,” October 13 2021; and related marker dossier and entries in the Racial Terror: Lynching in Virginia project. Wikipedia+2Va Historic Resources+2

“Jenkins, Kentucky lynching…” RareNewspapers.com description of the New York Times coverage, December 1 1927. Rare Newspapers+1

ExploreKYHistory and Kentucky Historical Society resources on Jenkins as a company town built by Consolidation Coal starting in 1912. 25