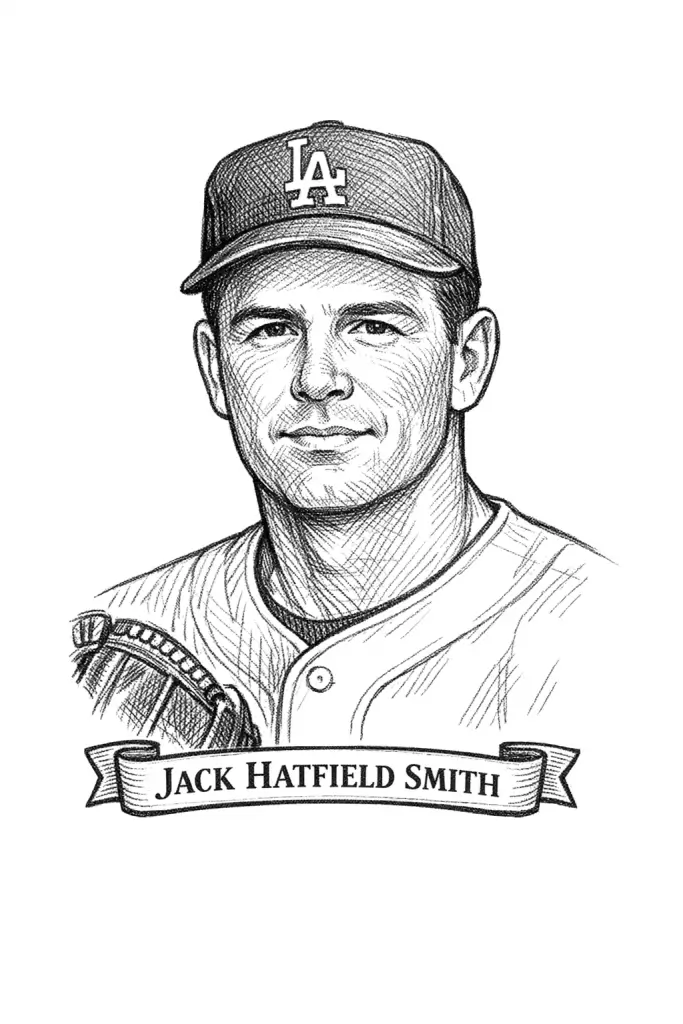

Appalachian Figures Series – The Story of Jack Hatfield Smith of Pike, Kentucky

On a cool October afternoon in 1962, the Los Angeles Dodgers and San Francisco Giants were still trying to decide a pennant. Television cameras followed stars like Willie Mays and Sandy Koufax, but for a brief moment the ball was in the hands of a right handed reliever from Pikeville, Kentucky. Jack Smith jogged in from the bullpen, a long way in every sense from the Tug Fork and the hills around Pikeville. In the scorebooks he would be a line in a box score. For Appalachia he was something else, proof that a kid from the coalfields could pitch his way into one of baseball’s great rivalries.

Jack Hatfield Smith’s major league career lasted only a few dozen games, all in relief, between 1962 and 1964. Behind those short numbers lay a much longer story that ran from Pikeville to Matewan, from low level bus leagues to a Triple A award sweep, and finally to a barber chair in Atlanta where customers realized the man cutting their hair had once faced big league hitters.

From Pikeville to Matewan

Jack Hatfield Smith was born on November 15, 1935, in Pikeville, Pike County, Kentucky. His middle name came from his mother’s side of the family, and his birthplace put him squarely inside the Upper Big Sandy region that has produced a quiet number of athletes over the last century. Local genealogical sources and memorial records list his parents as Opal Williamson and Woodrow Hatfield, tying him to surnames that recur throughout Tug Fork country.

Like many Pike County families, the Smiths did not stay put. Jack grew up mainly in Matewan, West Virginia, just across the river from the Kentucky line. In a 1958 baseball questionnaire he listed Matewan as his hometown, an answer that reflects the way Appalachian people often claim both their birthplace and the place where they came of age. At Magnolia High School he lettered in three sports, playing baseball, basketball, and football for a school that drew students from mining towns spread along the Tug Fork.

He married young, only a couple of months before graduation, and went to work around the coal industry in the off season, stressing to reporters that he worked above ground. Baseball was never guaranteed. It was something he chased on the side while doing the kind of jobs that anchored most families in the region.

When the Brooklyn Dodgers’ scout Jim Russell came through, he saw enough in the lanky right hander to offer a contract. Smith signed in 1955 and stepped into a farm system that was already famous for its depth.

A long road through the low minors

The box scores from Smith’s first years in professional baseball read like a map of mid century bus leagues. In 1955 he split his time among three Class D teams, including Donalson of the Alabama Florida League, picking up only a handful of wins while trying to adjust to professional hitters.

In 1956 he landed with the Reno Silver Sox of the Class C California League and started to show what his arm could do. Local coverage described him as a fast working, hard throwing right hander. Over 196 innings he struck out 141 batters and tied for the team lead in wins, even as his walk totals showed that his control still needed work.

The next season was harder. In 1957 he bounced through three Dodger affiliates and finished with a combined 6–15 record in the low minors. In one Pioneer League game he struck out thirteen batters in six innings, a reminder that his stuff was good enough to dominate in flashes, but he later admitted that wildness kept him from turning those flashes into a steady job.

After 1958, when he put together a solid year for Des Moines with double digit wins and a better walk rate, the business side of the game intervened. Contract disputes kept him out of organized baseball for the entire 1959 season. He went home, finished barber college, and went back to work. For an Appalachian ballplayer, that kind of detour was not unusual. The barber chair was a backup plan that fit the rhythm of a region where people expected to patch together multiple trades across a lifetime.

He returned to the Dodgers system in 1960 and pitched his way back up the ladder through Macon in the South Atlantic League and then Atlanta, where he joined the Crackers of the Southern Association. The Crackers had been called the Yankees of the Minors during their long run in Atlanta, and by 1960 they were the Dodgers’ Double A affiliate.

At first the Dodgers tried him as a starter. Late in the 1960 season, though, injuries shuffled the Atlanta staff and manager Rube Walker moved Smith into a long relief role. That decision changed his career.

Workhorse of Atlanta and Omaha

In 1961 Jack Smith became one of the most heavily used relievers in minor league baseball. Pitching for the Atlanta Crackers, he appeared in seventy games, almost all of them out of the bullpen. He went 12–7 with a 2.09 earned run average, striking out 111 batters in 155 innings and piling up twenty nine saves. He even pitched seventeen and a third innings over the final four games of the season so that he would have enough innings to qualify for the league ERA title, which he won.

The following year he moved up to the Triple A Omaha Dodgers of the American Association and somehow topped that work. In 1962 he appeared in another seventy games, winning seventeen, saving nineteen, and posting a 2.06 ERA while working almost exclusively in relief. The American Association named him both its Most Valuable Player and its Rookie of the Year, a rare double that placed his name alongside future stars like Barry Larkin and Juan González on the league’s historical award list.

For a man from Pikeville and Matewan who had nearly left baseball to cut hair full time, those seasons in Atlanta and Omaha were the high crest of a hard climb. They also came at a moment when the Dodgers needed exactly his kind of arm.

The Dodgers’ pennant race and a Pikeville pitcher

In late 1962 the Los Angeles Dodgers were locked in a fierce National League race with the San Francisco Giants. When injuries sidelined Sandy Koufax and reliever Larry Sherry, the club dipped into its farm system and brought Jack Smith up from Omaha when rosters expanded on September 1.

He made his major league debut on September 10, 1962, at Dodger Stadium against the Chicago Cubs. Don Drysdale had already secured his twenty fourth win of the season. Smith came on in the ninth with an 8–0 lead, gave up an infield hit and a run, then worked out of the inning. Under the scoring rules of the day, that outing gave him his only big league save.

Over the rest of the month he appeared in eight games. His most historically vivid work came in the best of three tie breaker series between the Dodgers and Giants after the clubs finished the regular season deadlocked. Smith pitched in the first two games of that series, logging two innings in relief, allowing two hits and only an unearned run. The Dodgers won one of those contests and lost one, then dropped Game Three and the pennant.

For most national fans, those tie breaker box scores belong to Willie Mays and the other headliners. For people in Pike County they mark the moment when a local boy carried the ball in one of the most dramatic finishes in National League history.

A rough outing and a final chance

Smith made the Dodgers’ Opening Day roster in 1963, but the season did not unfold the way his Omaha dominance had promised. He worked in four games in April and early May, and in three of them he gave up runs. The game that stuck with later writers came on May 3, 1963, against the Pittsburgh Pirates. Entering in relief, he was hit hard during a lopsided 13–2 loss. One modern account of the game describes it as the sort of outing that can haunt a pitcher whose grip on a roster spot is already precarious.

Shortly after that game the Dodgers sent him back to the minors, where he finished the year. That winter, on December 2, 1963, the Milwaukee Braves selected him in the major league phase of the Rule 5 draft, betting that his Triple A dominance might still translate if they gave him a longer look.

In 1964 the Braves used him as a middle reliever for the first three months of the season. He appeared in twenty two games, all out of the bullpen, and finally collected his only two major league wins. On April 28, 1964, he worked four innings of one run relief against the Pittsburgh Pirates to secure his first victory. On June 12 he held the San Francisco Giants hitless over three innings and earned his second.

His last major league appearance came a little more than a week later, on June 21, 1964, against the Houston Colt .45s. Soon afterward the Braves optioned him to their Triple A affiliate in Denver. He never returned to the big leagues and retired from professional baseball after the 1965 season.

Taken together, his major league numbers show a journeyman reliever who did his job more often than not. In thirty four games he pitched 49⅓ innings with a 2–2 record, a 4.56 ERA, thirty one strikeouts, and a single save. It was a modest line by big league standards and a remarkable one for a boy from Pikeville who had once wondered whether he would ever get beyond Class D ball.

Smitty’s Bullpen and Atlanta memories

When Jack Smith finally left organized baseball, he did not leave work. He settled in the Atlanta area and put his barber training to full use, opening and operating shops in downtown Atlanta and later near what is now Hartsfield Jackson International Airport. One of his shops carried the fitting name Smitty’s Bullpen.

Atlanta columnist Lewis Grizzard wrote about getting his hair cut by a former pitcher from the old Atlanta Crackers, a story later writers have linked back to Smith and his years moving between the Crackers and the majors. Customers might have noticed the steady hands and the easy conversation first. Only later, reading a column or a box score summary, would some realize that their barber had once faced big league sluggers in Los Angeles and Milwaukee.

Smith retired from barbering in 2016. He spent his later years in the Atlanta suburbs, where family members and obituaries place him in Loganville and Conyers. On April 7, 2021, he died at age eighty five at a rehabilitation facility in Conyers after a struggle with Alzheimer’s disease. He was buried back under the name Jack Hatfield Smith, with memorial records preserving his Pikeville birth and his Appalachian roots.

Remembering a Pike County pitcher

For researchers tracing baseball talent out of Kentucky, Smith’s name appears in statewide rankings of players by birthplace. One analysis of Kentucky born major leaguers lists him as Jack H. Smith of Pikeville, a right handed relief pitcher whose short time in the majors grew out of an extraordinary peak in the high minors. Reference works like Baseball Almanac and MLB’s own player pages repeat the same basic facts: born in Pikeville in 1935, six feet tall, 185 pounds, a right hander who debuted in 1962 and threw his last big league pitch in 1964.

Closer to home, local historians and enthusiasts have begun to fold him into Pike County’s own story. In a Pike County Historical Society feature about Philadelphia Phillies shortstop John O’Neil, the author mentions having sent along research on “sports heroes from the Pikeville area who had played major league baseball,” including Jack Smith, to help build a broader picture of the county’s athletic past. Posts from the Mountain Sports Hall of Fame in Wayland, Kentucky, also point to ongoing work on regional baseball figures like Smith, a reminder that his career still echoes in conversations about eastern Kentucky sports history.

For Appalachia, Jack Smith’s life sits at the intersection of several familiar themes. He grew up in coal country, balanced industrial work with sport, left home to chase a narrow chance, and eventually came back to an everyday trade that kept him close to working people. His best professional seasons unfolded not under the brightest lights but in crowded minor league parks in Atlanta and Omaha, where fans sat close enough to see the sweat on a reliever’s cap.

Yet whenever someone in Pike County scans an old American Association award list or looks up the box scores from the 1962 Dodgers Giants playoff, they find a name that started beside the Levisa Fork. For a few seasons in the early 1960s, the road from Pikeville to the National League ran through Jack Hatfield Smith’s right arm.

Sources & Further Reading

“Jack Smith Bio.” MLB.com. Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.mlb.com/player/jack-smith-122408 MLB.com

Baseball-Reference.com. “Jack Smith Stats, Height, Weight, Position, Rookie Status & More.” Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/s/smithja04.shtml Baseball Reference

Baseball Almanac. “Jack Smith Stats, Height, Weight, Research & History.” Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php?p=smithja04 Baseball Almanac

Baseball Almanac. “Box Score for Dodgers (2) vs. Pirates (13) on May 3, 1963.” Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.baseball-almanac.com/box-scores/boxscore.php?boxid=196305030PIT Baseball Almanac

StatsCrew.com. “1961 Atlanta Crackers Roster.” Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/roster/t-ac10221/y-1961 Stats Crew

StatsCrew.com. “1961 Southern Association Regular Season Standings.” Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/standings/l-SOUA/y-1961 Stats Crew

The Baseball Cube. “Jack Smith – MLB Baseball Statistics.” Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.thebaseballcube.com/content/player/18170/ The Baseball Cube

Retrosheet. “Retrosheet Game Logs and Box Scores.” Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.retrosheet.org/ retrosheet.org

“Jack Smith (1935-2021) – Find a Grave Memorial.” Find a Grave. Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/227317072/jack-smith Find a Grave

“Jack Smith Obituary (1935-2021).” Legacy.com / Atlanta Journal-Constitution. April 7, 2021. Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/atlanta/name/jack-smith-obituary?id=12187699 Legacy

Gazdziak, Sam. “Obituary: Jack Smith (1935-2021).” RIP Baseball. April 18, 2021. Accessed January 4, 2026. https://ripbaseball.com/2021/04/18/obituary-jack-smith-1935-2021/ RIP Baseball

Kallman, Jeff. “Jack Smith, RIP: Haircut, shave, and pension throat cut.” Throneberry Fields Forever. April 19, 2021. Accessed January 4, 2026. https://throneberryfields.com/2021/04/19/jack-smith-rip-haircut-shave-and-pension-throat-cut/ Throneberry Fields Forever

Dead Ballplayers Society. “Jack Smith (1935-2021).” Facebook. April 2021. Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.facebook.com/deadballplayerssociety/photos/a.649259281817193/3886486894761066/?locale=en_GB&type=3 Facebook

Wikipedia. “Jack Smith (pitcher).” Last modified 2024. Accessed January 4, 2026. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Smith_%28pitcher%29 Wikipedia

Baseball-Reference.com. “Jack Smith (smithja04).” BR Bullpen. May 12, 2021. Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Jack_Smith_%28smithja04%29 Baseball Reference

AinsworthSports.com. “The Top Ranked Baseball Players of All-Time from Kentucky.” Accessed January 4, 2026. https://ainsworthsports.com/baseball_player_rankings_by_state_ky.htm ainsworthsports.com

Wikipedia. “1962 International League Season.” Accessed January 4, 2026. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1962_International_League_season Wikipedia

Baseball Almanac. “Jack Smith Trades and Transactions.” Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/trades.php?p=smithja04 MLB.com

https://doi.org/10.59350/x5n8a-5rb69

Author Note: As a historian who cares deeply about Appalachian athletes, I am drawn to careers that look small in the record books but loom large in local memory. I hope this piece helps you see Jack Smith’s short major league run as part of a longer Appalachian story that stretches from Pikeville and Matewan to barbershops and ballparks far from the Tug Fork.