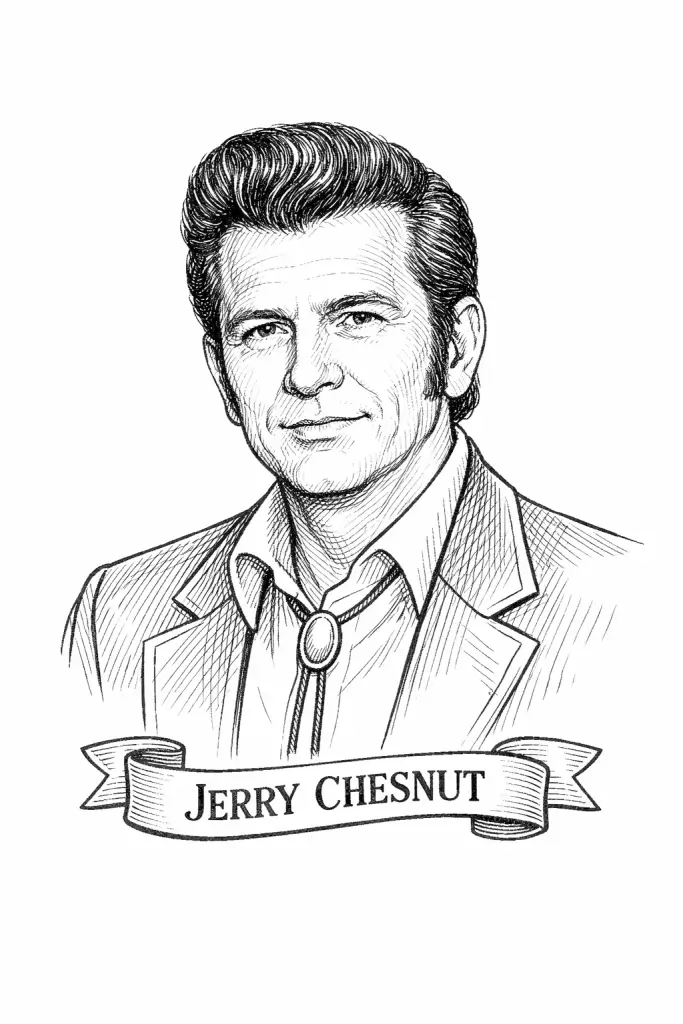

Appalachian Figures Series – The Story of Jerry Chesnut of Harlan, Kentucky

If you drive into Loyall from the riverside, the first thing that catches your eye is not a coal tipple or the old Louisville and Nashville yard but a roadside sign. A stretch of Kentucky 840 is officially the Jerry Chesnut Highway, a reminder that one of Nashville’s sharpest country songwriters came out of this small railroad and coal town in Harlan County. His songs traveled a long way from Clover Fork, turning up in the voices of George Jones, Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, Faron Young, Elvis Presley, Travis Tritt, and dozens more. Yet the stories he told almost always carried the feel of a coal camp kitchen or a hard day on the job.

This is the story of Jerry Donald Chesnut, the boy from Loyall whose songs carried Harlan County out into the wider world.

A coal camp boy in Loyall

Jerry Donald Chesnut was born on May 7, 1931, in Loyall, Harlan County, Kentucky, to Alvin Basil and Ruby Chesnut. The town itself had been built up around the big L and N yard that marshaled coal from dozens of Harlan County camps. By the time Jerry arrived, the county had already earned the nickname “Bloody Harlan” from the violent labor struggles of the 1930s, and coal still ruled the economy and the landscape.

The 1940 federal census catches the family in the Loyall precinct, with A. B. and Ruby Chesnut raising sons Alvin Ray and Jerry D. in a railroad and coal town where whistles and tipple machinery set the daily rhythm. In his later years Jerry remembered his father as the kind of man who did whatever work needed done to keep a family afloat, from hauling logs to cutting meat, a worker who moved where the jobs were in a region that lurched from boom to bust.

In that world, money was tight and houses were humble. Harlan County coal camps in the 1930s and 1940s commonly offered only basic company housing, shared water, and long days underground for the men. Jerry’s childhood unfolded in those conditions. Later he would say that when it came time to write about the Depression and hard times, he “had no problem with getting lines for all that, because [he] had been through that.”

Learning the sound of the coalfields

Like a lot of Harlan County kids, Jerry found music first through the radio. From Loyall he could pick up WSM’s Grand Ole Opry out of Nashville and WNOX’s Midday Merry Go Round from Knoxville, shows that beamed in honky tonk and string band music to coal camp living rooms.

According to the Country Music Hall of Fame and later obituaries, his older brother bought a guitar and refused to let Jerry touch it. That challenge pushed the younger Chesnut to sneak time with the instrument until he could play it as well as, or better than, his brother. In the Poets and Prophets oral history he recalls singing in coal camps and learning the repertoire his neighbors wanted to hear: songs about love gone bad, hard work, and family.

School records, yearbooks, and local reminiscences place him at Loyall High School in the 1940s, part of a generation that grew up in the shadow of both the Harlan County Wars and World War II. The coal and railroad economy gave Loyall a steady hum of traffic and jobs, but it also produced the kind of long hours and precarious paychecks that would later echo through Jerry’s lyrics.

Air Force years and a Florida boss named Oney

In 1949, just before the Korean War fully escalated, Chesnut enlisted in the United States Air Force. During four years of service he played guitar and sang country songs on naval ships, at military bases, and even on radio programs from stations such as KFRE in Fresno, California. One of the crowd favorites was Hank Thompson’s “The Wild Side of Life.” Performing it night after night made him think seriously about writing songs of his own for the artists he admired.

After his discharge he headed not yet for Nashville but for Florida. In St. Augustine he worked as a conductor on the Florida East Coast Railway and played in bands on the side, sometimes performing on local radio. There he encountered a tough supervisor named Oney, whose manner stuck with him. Years later Chesnut would immortalize that boss as the title character in “Oney,” the Johnny Cash song about a working man who dreams of telling off his foreman on retirement day.

Even in Florida, the sensibility he carried came from Harlan County. His songs from this period dwelled on bosses, jobs that wear a person down, and the narrow space working people have to claim their dignity. The coal camp had simply traded places with a railroad yard and a factory floor.

Nine hard years on Music Row

By 1958 Chesnut decided to “test the waters” in Nashville. He moved from Florida to Music City with the familiar Appalachian dream of turning musical talent into a livelihood. Nashville did not roll out a red carpet. For nine years he held regular jobs, including a stint as a door to door vacuum cleaner salesman, while making the rounds of publishers and labels on Music Row.

In interviews he remembered those years as a time of constant rewriting and stubborn refusal to quit. The work ethic he had seen in his parents was simply applied to songs instead of coal or timber. The payoff finally came in 1967 when Del Reeves cut “A Dime at a Time,” giving Chesnut his first charting single. Reeves soon recorded “Looking at the World Through a Windshield,” another Chesnut song that turned long hours on the road into a vivid, blue-collar story.

Then the hits began to stack up. Jerry Lee Lewis took “Another Place, Another Time” into the country Top 10 in 1968 and landed Chesnut his first Grammy nomination. Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton scored a hit with “Holding on to Nothin’” that same year. Del Reeves returned to Chesnut material with “Good Time Charley’s.” Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, major stars kept picking his songs, and nearly all of them carried some trace of the hard-working, no-nonsense world he came from.

Songs that sounded like Harlan County

Two of Chesnut’s most enduring songs, “They Do not Make ’Em Like My Daddy” and “The Wonders You Perform,” grew directly from his childhood memories and sense of faith.

In the Country Music Hall of Fame interview, host Michael Gray asked about “They Do not Make ’Em Like My Daddy,” the Loretta Lynn hit that salutes an older generation of fathers. Chesnut explained that he had written it while thinking about his own father, who had done whatever work was necessary to keep the family going in Harlan County. He said he had no trouble finding lines about the Depression and hard times because he had lived through them. The song’s details about pride, persistence, and a man who never quits are essentially a Harlan coalfield biography set to music.

“The Wonders You Perform,” recorded by Tammy Wynette around 1970, grew from what Chesnut called “getting these lines from God or somewhere,” a burst of inspiration that he connected to his experiences of faith and struggle. “A Good Year for the Roses,” made famous by George Jones, came from a conversation at a garden center that sparked a portrait of a marriage falling apart amid the ordinary chores of a yard.

Even when the surface stories were about love, the underlying world of these songs is the one he knew from Harlan County and working-class Florida. Jobs are tenuous, tempers short, money scarce, but dignity and stubbornness run deep.

Elvis, Hee Haw, and “T R O U B L E”

In the 1970s Chesnut’s songs crossed from country charts into the broader popular imagination. Faron Young’s recording of “It’s Four in the Morning” hit number one on the country chart and even nicked the pop charts, later being revived by Elvis Costello. George Jones’s “A Good Year for the Roses” became one of his signature heartbreak performances and spawned covers far beyond the country world.

Then came Elvis. In 1974, Presley cut Chesnut’s ballad “It’s Midnight,” starting a late career relationship in which Elvis recorded a string of his songs. The most famous would be “T R O U B L E.” Chesnut originally wrote it for barroom piano player Little David Wilkins, playing off the way people spell names in their heads and realizing he could rhyme not just words but letters themselves. Elvis Presley turned it into a 1975 hit, and nearly twenty years later Travis Tritt’s version reintroduced it to a new generation. By 2010 BMI certified that “T R O U B L E” had been played more than four million times on radio and other platforms.

Chesnut also made occasional records as a performer, cutting a handful of singles for United Artists in the early 1970s, and he became a recurring presence on the television show Hee Haw. He never quite broke through as a star singer, but his personality and storytelling shone in interviews and TV appearances where he came across very much like the men he wrote about.

In 1971 Billboard named him Country Songwriter of the Year, recognition that echoed an earlier moment when industry awards placed him at the very center of Nashville’s writing community. He would go on to be inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1996 and the Kentucky Music Hall of Fame in 2004.

Honors at home and a life’s end

Even as Chesnut built a life in Nashville and Florida, his home county did not forget him. Harlan County histories and local notables lists regularly include him as “country music songwriter” alongside authors, coaches, and veterans. Facebook groups built around Harlan County photographs and memories share birthday tributes that call him “Harlan County (Loyall), Kentucky’s very own, Jerry Donald Chesnut” and pass around old images of Loyall School with his name in the caption.

In 2010 the Kentucky General Assembly passed a resolution directing that the portion of Kentucky Highway 840 running through Loyall be designated the Jerry Chesnut Highway, a symbolic way of tying his name back to the roadbed that carried coal and people in and out of his hometown.MusicRow’s obituary on his death made a point of noting that honor along with the fact that more than one hundred artists, including thirty Country Music Hall of Famers, had recorded his songs.

Jerry Chesnut died in Brentwood, Tennessee, on December 15, 2018, at the age of eighty seven. His funeral service and burial took place at Woodlawn Memorial Park in Nashville, with fellow songwriters and industry figures named as honorary pallbearers, but the news resonated strongly back in the mountains. WYMT in Hazard introduced him to its viewers as a “Harlan County native” from Loyall whose songs had been sung by George Jones, Loretta Lynn, and Dolly Parton.

In the years since, American Songwriter and other outlets have run retrospectives on his catalog, reminding readers that the man behind “A Good Year for the Roses,” “It’s Four in the Morning,” and “T R O U B L E” grew up singing in Harlan County coal camps.

Why Jerry Chesnut matters to Appalachian history

For Appalachian history, Chesnut’s life illustrates how coalfields culture spread far beyond the hollers where it began. He was not a protest singer in the style of Florence Reece or a ballad collector like Josiah Combs. Instead he did what most working people do: he took the world he knew and folded it quietly into the job in front of him.

His job happened to be songwriting. The bosses and working stiffs in “Oney,” the proud father in “They Do not Make ’Em Like My Daddy,” the weary lovers in “A Good Year for the Roses,” the man staring at a clock in “It’s Four in the Morning” all carry a trace of the coal camps and railroad yards of Harlan County. They speak from a place where work is never fully secure, where families live on the edge but keep going, and where humor and stubbornness act as a kind of survival gear.

Today the Jerry Chesnut Highway dips through Loyall not far from where the 1940 census once counted a little boy named Jerry D. in a worker’s household. His grave is hundreds of miles away in Nashville, and his songs now belong to stages and playlists across the world. But for Appalachian history, he remains first and last a Harlan County songwriter, someone who learned his craft in a coal camp world and then carried that world with him into every song he wrote.

Sources & Further Reading

Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. “Poets and Prophets: Legendary Country Songwriter Jerry Chesnut.” Video oral-history program, September 26, 2009. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.countrymusichalloffame.org

Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame. “Jerry Chesnut.” Inductee biography. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.nashvillesongwritersfoundation.com

Kentucky Music Hall of Fame and Museum. “Jerry Chesnut.” Hall of Fame profile. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.kentuckymusichalloffame.com

Jerry Chesnut Music. “Biography.” Official estate website of Jerry Chesnut. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.jerrychesnutmusic.com

“U.S., Korean War Era Draft Cards, 1948–1959.” Database on-line. Ancestry. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.ancestry.com

“1940 U.S. Federal Census of Loyall, Harlan, Kentucky.” Index to the 1940 census for Loyall, Harlan County, Kentucky. LDSGenealogy. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://ldsgenealogy.com/KY/1940-Census-Loyall-KY.htm

“Loyall Genealogy Resources & Vital Records, Harlan County, Kentucky.” Forebears. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://forebears.io

“Jerry Chesnut Obituary – Nashville, TN.” Woodlawn-Roesch-Patton Funeral Home and Memorial Park obituaries. Dignity Memorial. December 2018. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.dignitymemorial.com

“Jerry Donald ‘Jerry’ Chesnut.” Memorial page. Find a Grave. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.findagrave.com

Songcraft: Spotlight on Songwriters. “Episode 55: Jerry Chesnut (T-R-O-U-B-L-E).” Podcast audio, 2017. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://songcraftshow.com

Nashville Songwriters Association International. “Behind the Song: ‘T-R-O-U-B-L-E’ with Jerry Chesnut.” Interview feature. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.nashvillesongwriters.com

Oermann, Robert K. “Hit Country Songwriter Jerry Chesnut Passes.” MusicRow, December 17, 2018. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.musicrow.com

Stefano, Angela. “Songwriter Jerry Chesnut Dead at 87.” The Boot, December 17, 2018. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://theboot.com

“‘T-R-O-U-B-L-E’ Songwriter Jerry Chesnut Dies.” Taste of Country, December 17, 2018. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://tasteofcountry.com

“Elvis Presley, George Jones Songwriter Jerry Chesnut Dead at 87.” Rolling Stone, December 18, 2018. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.rollingstone.com

Patterson, Melissa. “Country Songwriter Jerry Chesnut, Who Penned Hits for Elvis and George Jones, Dies at 87.” The Tennessean, December 17, 2018. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.tennessean.com

WYMT News Staff. “Harlan County Native, Hall of Fame Songwriter Dies in Nashville.” WYMT (Hazard, Kentucky), December 17, 2018. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.wymt.com

Cackett, Alan. “Jerry Chesnut Obituary.” AlanCackett.com, December 2018. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.alancackett.com

“Jerry Chesnut, Songwriter Who Composed Hits for Stars like Elvis Presley, Elvis Costello and Dolly Parton – Obituary.” The Telegraph (London), December 18, 2018. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.telegraph.co.uk

“On This Day in 2018, We Said Goodbye to the Songwriter Who Penned Hits for George Jones, Johnny Cash, Mel Tillis and More.” American Songwriter, December 15, 2025. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://americansongwriter.com

“Jerry Chesnut.” AllMusic, artist biography and discography entry. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.allmusic.com

“Jerry Chesnut.” Songwriter profile. SecondHandSongs. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://secondhandsongs.com

“Jerry Chesnut.” Mini-biography. Rocky-52 Country Music. Accessed December 28, 2025. http://www.rocky-52.net

“Jerry Chesnut.” Wikipedia, last modified 2025. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org

“Harlan County, Kentucky.” Wikipedia. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org

“Loyall, Kentucky.” Wikipedia. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org

“Harlan County, Kentucky Genealogy.” County research guide. FamilySearch Wiki. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://www.familysearch.org

Author Note: As a Harlan County writer, I wanted to trace Jerry Chesnut’s road from Loyall’s coal camps to Nashville’s studios so readers here at home can see just how far our hills have always reached. I hope this piece helps you hear his songs a little differently, with Harlan’s trains, tipples, and kitchen-table stories sounding quietly underneath every line.