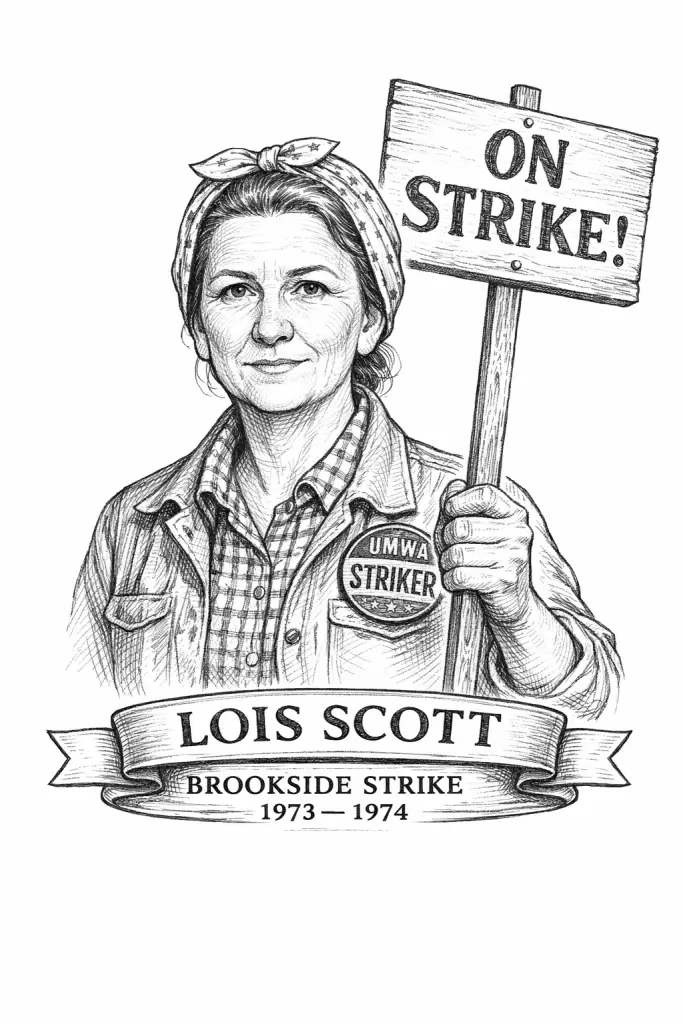

Appalachian Figures Series – The Story of Lois Scott of Harlan, Kentucky

In Barbara Kopple’s documentary Harlan County, U.S.A., there is a moment that has become coalfield legend. In a crowded union hall a middle aged Harlan County woman in a simple dress stands up to speak. As tempers rise she calmly reaches into her bra and produces a pistol, a small but unmistakable reminder that the families on the Brookside picket line are not backing down.

The woman is Lois Scott of Harlan County. For many viewers that brief scene is their first glimpse of her, but it represents only one flash from a much longer story. She was a coal camp daughter born at the onset of the Great Depression, a miner’s wife who helped hold a strike together in the 1970s, and a voice that later historians would treat as central to the story of Appalachian women’s activism.

Benham beginnings and coal camp lessons

Lois Scott was born on 3 November 1929 in the coal company town of Benham in Harlan County, Kentucky. Near contemporary memorial and genealogical records list her as Lois Geraldine Jones Scott and give Benham as her birthplace and Harlan County as the place where she died in 2004, with burial at Peaceful Acres Cemetery in Hiram.

Benham in the 1930s was a classic Harlan County coal camp. Houses, stores, and much of daily life were tied to the company that controlled the mine. Oral history project descriptions for interviews recorded with her in the 1980s note that she talked about growing up in that setting, about family life that revolved around the mines, church, and the unwritten rules of a company town.

Later scholarship that draws on those interviews remembers her as a woman who carried childhood lessons about injury and injustice into her organizing years. Historian Jessica Wilkerson, paraphrasing an interview with Scott, notes that the Brookside struggle gave Lois a chance to express “the hatred [she] fe[lt] for the coal operator for what he had done to [her] father and to [her] brother and the family.”

By the time the Brookside strike began in 1973, Scott was a middle aged woman with children and grandchildren. One daughter, Bessie, would stand beside her on the picket line and later testify with her at a citizen inquiry into the strike.

Brookside before the women took the line

The Brookside mine sat along Clear Creek in Harlan County, part of Eastover Mining Company and tied to Duke Power’s larger system. In 1973 the miners there voted to join the United Mine Workers of America. Eastover refused to sign a standard union contract and tried instead to keep a company favored union in place. The result was a strike that quickly became a test of union power, corporate stubbornness, and the willingness of state authorities to protect company property instead of picketing miners.

The conflict did not come out of nowhere. Harlan County already carried the reputation of “Bloody Harlan” from the 1930s, when coal operators hired private guards and public officials to crush union drives. The Brookside dispute unfolded in that long shadow. Armed company guards, strikebreakers, and state police appeared on the roads and bridges around the mine almost as soon as pickets went up. Shots were fired into homes, cars were forced through picket lines, and injunctions from Judge Byrd Hogg tried to limit how many people could stand on the roadside.

In that tightening climate women like Lois Scott stepped forward. They were not on the company payroll, but they were the ones hauling water, feeding children, and living with the fear that a husband might not come home alive.

“If the women did not come in, there would be violence”

One of the richest near primary accounts of the Brookside women is Senator Fred Harris’s long article “Burning Up People to Make Electricity,” written after he served on a citizen panel that investigated the strike. Harris describes a march in Harlan on September 27, 1973, when miners’ wives and family members took the streets in support of the strike. Afterward, a group of women waited near the picket line at Brookside as nonunion workers tried to drive out of the mine.

According to Harris’s account, some of the women cut switches from nearby bushes and joined the picketers at the road. When a company guard pointed a gun at them, Lois Scott broke a switch over his head and the younger guard backing him up retreated. As Harris recounts it, Scott and the others decided that women had to come onto the line because they believed their presence might keep a violent situation from turning deadly.

That day helped spark the formation of the Brookside Women’s Club, an organization of miners’ wives and female relatives who began planning marches, support work, and strategic acts of civil disobedience. Harris writes that after the first confrontations, company officials asked Judge Hogg to hold the union and several named miners and women in contempt for violating an order limiting pickets. The judge fined the UMWA twenty thousand dollars and sent the group to jail.

Women like Lois Scott took their children with them to the Harlan County jail rather than abandon the strike. Harris records that when a welfare official threatened to remove the children if they stayed overnight behind bars, the mothers insisted that taking the children would mean taking them too. Relatives eventually took the children home, but the determination of the women forced local authorities and company officials to confront the cost of prosecuting family members rather than named union officers.

A month later the Brookside women organized what they called a sunrise worship service on the tracks and road opposite the mine, starting in the dark at four thirty in the morning. Seventy five state police officers turned out. Faced with a line of troopers and the prospect of scabs crossing the line, the women decided that their choices were to fight, stand aside, or lie down. They chose to lie in the road. When a state police captain tried to drag one woman away, others swung the sticks they had brought with them.

For Scott and her peers, this was not a symbolic gesture. The sticks were a deliberate escalation from the switches they had used earlier, a way to meet what they had already seen on the line. In Harris’s narrative she explains that after looking into car windows and seeing pistols in the front seat of almost every strikebreaker’s vehicle, and after watching a company guard aim a submachine gun from the company office porch, the women decided they could not meet guns with green twigs.

Citizens’ Public Inquiry at Evarts

In March 1974 the Brookside dispute came under national scrutiny at the Citizens’ Public Inquiry into the Brookside Strike, held at the Evarts Multipurpose Center. This independent panel, funded by the Marshall Field Foundation, brought together eleven prominent clergy, academics, and public figures, including Senator Harris, to hear sworn testimony from miners, company representatives, and local officials. Their proceedings were recorded and later published in a three hundred page volume, giving historians an unusually detailed record of how people in Harlan County described the strike in their own words.

Harris devoted part of his Atlantic article to what he called “women’s day” at the inquiry. Eleven women took the stage together for support. He describes Lois Scott as a woman in her mid forties with a hard edge in her voice and flashing blue gray eyes, leading off their testimony. Scott explains how some of the women hid from process servers so they could appear before the inquiry instead of being jailed for contempt, describes forming the Brookside Women’s Club, and traces the march, the switch and stick confrontations, and the nights in jail.

The women also submitted a report from the Harlan County Health Department which found that drinking water in the Eastover camp was “highly contaminated” with fecal bacteria. Only a few of the homes had indoor plumbing, and one of the septic systems had been out of order for months. To the women this was not an abstract sanitary problem. It was another example of how the company treated miners’ families as expendable even while insisting that the mine was essential to the region.

Government records from the same period mention the inquiry and its findings. Congressional Record entries summarizing the panel’s work note that the proceedings in Evarts helped build national pressure on Duke Power to settle, even though the inquiry had no formal legal authority.

On screen in Harlan County, U.S.A.

When Barbara Kopple and her crew arrived in Harlan County to film the strike, they found much of the story already playing out through the words and actions of women like Lois Scott. The resulting documentary, Harlan County, U.S.A., follows the strike from picket lines to kitchen tables and union halls. Its film reference entries and later write ups consistently identify Scott as one of the central personalities in the story.

In one of the most remembered scenes Scott stands in a crowded meeting, arguing that the company’s violence means the miners’ families cannot afford to stay unarmed. As the argument heats up, she pulls a small pistol from her bra, holds it up matter of factly, and stuffs it back again. For viewers unfamiliar with the background, it can look like pure bravado. Placed alongside the testimony in the Citizens’ Inquiry transcript and Harris’s descriptions of armed guards, gunfire, and threats, the scene reads very differently. It becomes a statement that the women understood the risks they faced and were unwilling to meet high powered weapons with nothing but bare hands.

Film critics have taken notice. Writing for the Criterion Collection, Paul Arthur called Basil Collins, the company’s hired enforcer, and Lois Scott the two strongest personalities in the film and used her to explore questions about the ethics and necessity of militant resistance. Early radical film criticism in journals like Jump Cut dwelt on the same scenes, treating Scott’s presence on screen as evidence that miners’ wives were not simply background figures but active protagonists in the drama.

Later essays, such as an Oxford American piece titled “The Ballad of Harlan County” and a reflection in Appalachian Voices on the film’s continuing relevance, portray Scott as one of the most memorable women in Harlan County, U.S.A., both for her sharp tongue and for the way she led fellow wives on the line.

Lois Scott in her own words

The filmed scenes and Atlantic article capture Lois Scott in the heat of the 1973 and 1974 conflict, but the richest record of her life and thinking comes from oral history projects conducted more than a decade later. In the mid 1980s the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky recorded a series of interviews with Scott as part of a Women in the Brookside Strike project. Finding aids for those recordings note that she talks about her childhood in Benham, her family and church life, her path into the Brookside struggle, and the founding of the Brookside Women’s Club. She also reflects on politics, gender, and the way the strike changed her understanding of herself.

One Nunn Center description explains that she remembered the appreciation that older retired miners expressed for what the women had done, even as some local people criticized the wives for stepping out of what they considered proper roles. Another notes that Scott discussed dividing labor among the women, arranging childcare, and deciding who would stand on the line and who would help keep households afloat when the men’s wages were cut off.

Historians who have listened closely to those tapes hear more than a colorful character. They hear a working class woman who understood herself as both a mother and a political actor. Wilkerson’s work, which relies heavily on Scott’s oral histories, places her at the center of a coalfield feminist tradition that saw caring for family and confronting company power as part of the same calling.

Beyond Brookside: more strikes and a long life in Harlan County

Brookside did not end Lois Scott’s activism. Later Nunn Center interviews and project notes indicate that she remained involved in labor struggles at places like Highsplint and in actions around Pikeville. She continued to lend her voice and organizing experience when other miners faced layoffs, safety violations, or company pressure.

Public records and memorial pages show that she stayed in Harlan County after the cameras left and the strike was over. She died in Harlan on 15 May 2004 at the age of seventy four and was buried at Peaceful Acres Cemetery. Genealogical entries linked to a family tree and obituary notice point researchers to local newspaper microfilm, likely the Harlan Daily Enterprise, for a full obituary that would give more detail on her children, grandchildren, and church memberships.

In that sense her story remained local even while film and scholarship carried her image far beyond the county line. For neighbors who knew her, she was a Benham girl, a Brookside striker, a mother and grandmother, and later an elder who could look back on hard seasons with both anger and humor.

Historians, feminism, and the legacy of Brookside

Within a few years of the strike, scholars of labor and gender history began using the Brookside women to challenge older narratives that pushed women to the margins of coalfield stories. Lynda Ann Ewen’s book Which Side Are You On? The Brookside Mine Strike in Harlan County, Kentucky, 1973–1974 drew on diaries kept by Lois Scott and fellow striker Marilyn Pearson to build one of the first book length narratives of the strike. Those diaries, combined with interviews and transcripts, let Ewen tell the story of Brookside from the kitchen table out to the picket line.

Sociologist Sally Ward Maggard deepened that work in a series of articles and her 1988 doctoral dissertation Eastern Kentucky Women on Strike. In “Women’s Participation in the Brookside Coal Strike: Militance, Class, and Gender in Appalachia” and in the later essay “Gender Contested” she analyzes miners’ wives as political actors. Maggard argues that women like Scott moved from support roles into visible, sometimes militant leadership, and that this shift exposed tensions between working class feminism in the coalfields and more middle class feminist movements.

Wilkerson’s book To Live Here, You Have to Fight places Brookside in a larger history of Appalachian women’s movements from the War on Poverty through environmental justice campaigns and the Pittston strike. She treats Lois Scott and her daughter Bessie Lou as part of a multi generation tradition of activism, linking the Brookside Women’s Club to later groups like the Daughters of Mother Jones who carried picket signs in Virginia in 1989.

Barbara Ellen Smith’s influential essay “Walk Ons in the Third Act: The Role of Women in Appalachian Historiography” helped shift academic attention toward figures like Scott. Smith argued that women often entered the historical stage late in earlier scholarship, appearing as background characters rather than central protagonists. By foregrounding miners’ wives at Brookside she helped move Scott from the edge of the frame to the center of the story.

More recent theses and studies on Appalachian women’s activism, including work by Krystal Carter and Chiara Bagnoli, treat Brookside as a key case study when they discuss how Appalachian women used identities as mothers, church members, and community leaders to justify stepping into public fights over labor and the environment.

Even where Lois Scott’s name does not appear, her example lingers. Studies of environmental justice movements in the coalfields point back to the 1970s when women in places like Brookside discovered that confronting strip mining, black lung, and unsafe working conditions meant confronting the same systems that had once controlled their fathers’ and husbands’ lives.

Why Lois Scott’s story matters

Today Harlan County, U.S.A. continues to circulate in film classes and labor history courses, and the pistol in the bra scene still draws reactions. The Citizens’ Public Inquiry transcript, the union correspondence, the Council of the Southern Mountains records, and the oral history tapes at the Nunn Center all preserve Scott’s life in more complicated detail. Together they show a woman who could pray at a sunrise service and swing a stick at a state police captain, who cared deeply about her family and neighbors, and who learned to speak with authority in public even when judges and company men tried to silence her.

For Appalachian history, Lois Scott’s story pushes back against stereotypes of the region as either passive victim or lawless backcountry. For the history of women’s movements, it anchors big theoretical debates in the life of one coal miner’s daughter from Benham who decided that defending her family meant standing in the road at daybreak in front of a convoy of strikebreakers.

That is the history the records preserve.

Sources & Further Reading

Citizens’ Public Inquiry into the Brookside Strike. Proceedings of the Citizens’ Public Inquiry into the Brookside Strike, March 11 and 12, 1974, Harlan County, Kentucky. Evarts, KY: Citizens’ Public Inquiry into the Brookside Strike, 1974. http://textarchive.ru/c-1527283-pall.html Text Archive

Harris, Fred. “Burning Up People to Make Electricity.” The Atlantic, July 1974. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1974/07/burning-up-people-to-make-electricity/304563/ The Atlantic

Kopple, Barbara, dir. Harlan County, USA. Documentary film. Cabin Creek Films / Cinema 5, 1976. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harlan_County,_USA Wikipedia

“Harlan County, USA.” American Film Institute Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. https://catalog.afi.com/Film/55432-HARLAN-COUNTYUSA

“Harlan County, USA.” National Film Registry Essay. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/programs/national-film-preservation-board/film-registry/harlan-county-usa/

Arthur, Paul. “Harlan County USA: No Neutrals There.” The Criterion Collection / Current, May 22, 2006. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/415-harlan-county-usa-no-neutrals-there

Biskind, Peter. “Harlan County, USA: The Miners’ Struggle.” Jump Cut 14 (1977): 3–4. https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC14folder/HarlanCoUSA.html CliffsNotes

Haberkamp, Randy. “Harlan County, USA.” National Film Registry Essay. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/static/programs/national-film-preservation-board/documents/harlan_county.pdf

“The Ballad of Harlan County.” Oxford American, July 11, 2016. https://oxfordamerican.org/magazine/issue-93-summer-2016/the-ballad-of-harlan-county Oxford American

“To Be Somebody: Appalachian Women Make Their Voices Heard.” Scalawag, 2019. https://scalawagmagazine.org/2019/03/to-be-somebody-appalachian-women/

“Harlan County Goes to Hollywood (Again).” Appalachian Voices, c. 2000. https://appvoices.org/2000/12/01/2413/

“Program about the Harlan County, USA Documentary Film.” WYSO radio broadcast. American Archive of Public Broadcasting. http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-27-5m6251fx0z American Archive

Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History. Appalachia: Brookside Mine Strike (1973–1974) Oral History Project. University of Kentucky Libraries. Representative item: “Interview with Lois Scott, August 26, 1986.” https://nunncenter.net/ohms-spokedb/render.php?cachefile=2018oh525_ws148_ohm.xml Nunn Center

Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History. “Interview with Lois Scott, August 27, 1986.” Women and Collective Protest Oral History Project. University of Kentucky Libraries. https://nunncenter.net/ohms-spokedb/render.php?cachefile=2018oh526_ws149_ohm.xml Nunn Center

Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History. “Interview with Lois Scott, August 28, 1986.” Women and Collective Protest Oral History Project. University of Kentucky Libraries. https://nunncenter.net/ohms-spokedb/render.php?cachefile=2018oh527_ws150_ohm.xml Nunn Center

Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History. “Interview with Lois Scott, September 11, 1986.” Women and Collective Protest Oral History Project. University of Kentucky Libraries. https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/ark:/16417/xt7p5h7bvw1b Kentucky Oral History

Kentucky Oral History Commission / Nunn Center. “Interview with Ruby and Louie Stacy, October 8, 1986.” Women and Collective Protest Oral History Project. University of Kentucky Libraries. https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/search?query=Ruby%20Stacy Kentucky Oral History Library

Nunn Center for Oral History. Appalachia: Brookside Mine Strike (1973–1974) Oral History Project. Collection overview. https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/collections/appalachia-brookside-mine-strike-1973-1974-oral-history-project Kentucky Oral History

Southern Oral History Program. “The Duke Power Strike at Brookside Mine in Harlan County, Kentucky.” Excerpt from interview with Daniel H. Pollitt. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/L-0064-9/excerpts/excerpt_8975.html Documenting the American South

United Mine Workers of America Archives. “Correspondence – Brookside Strike.” In J. Davitt McAteer Papers, A&M 4219. West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University. Finding aid: https://archives.lib.wvu.edu/repositories/2/resources/2050 Ejumpcut

Pennsylvania State University Libraries. “United Mine Workers of America Archives.” Eberly Family Special Collections Library. Series descriptions for Brookside strike correspondence. https://libraries.psu.edu/findingaids/1208.htm

Council of the Southern Mountains. Council of the Southern Mountains Records, 1970–1989. Special Collections & Archives, Berea College. Finding aid: https://bereaarchives.libraryhost.com/repositories/2/resources/299 Berea College Archives

“Brookside Strike, 1974–1977.” In Council of the Southern Mountains Records, 1970–1989, Newspaper Clippings, Box 214, Folder 2. Berea College Special Collections and Archives. https://bereaarchives.libraryhost.com/repositories/2/top_containers/40511 Berea College Archives

U.S. Congress. House Committee on Education and Labor. Oversight Hearing on the Brookside Mine Labor-Management Dispute, Harlan County, Kentucky. 93rd Cong., 2nd sess., July 1974. Google Books scan. https://books.google.com (search “Oversight hearing on the Brookside Mine labor–management dispute”) Oxford American

U.S. Congress. Congressional Record. 93rd Cong., 2nd sess., vol. 120, pt. 29 (December 3, 1974). “Extensions of Remarks” noting the Citizens’ Public Inquiry into the Brookside Strike. https://www.congress.gov/bound-congressional-record/1974/12/03/extensions-of-remarks-section Facebook

“We Remember: Lois Scott (1929–2004).” We Remember memorial. https://www.weremember.com/lois-scott/9d7t/memories WeRemember

“Lois G. Jones Scott (1929–2004).” Find A Grave memorial 112033817, Peaceful Acres Cemetery, Hiram, Kentucky. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/112033817/lois-g-scott Find A Grave

“Lois Geraldine Scott (Jones) (1929–2004).” Geni.com profile. https://www.geni.com/people/Lois-Scott/6000000056966850875 Geni

Ewen, Lynda Ann. Which Side Are You On? The Brookside Mine Strike in Harlan County, Kentucky, 1973–1974. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Institute for Labor Studies, 1979. WorldCat record: https://www.worldcat.org/title/4448122

Maggard, Sally Ward (Sally Ward Maggard). “Women’s Participation in the Brookside Coal Strike: Militance, Class, and Gender in Appalachia.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 9, no. 3 (1987): 16–21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3346404

Maggard, Sally Ward. Eastern Kentucky Women on Strike: A Study of Gender, Class, and Political Action in the 1970s. PhD diss., University of Kentucky, 1988. University of Kentucky Libraries. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/sociology_etds/31 The Criterion Collection

Maggard, Sally Ward. “Gender Contested: Women’s Participation in the Brookside Coal Strike.” In Guida West and Rhoda Lois Blumberg, eds., Women and Social Protest, 75–98. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/089124390004004007 Wikipedia

Wilkerson, Jessica. “The Company Owns the Mine but They Don’t Own Us: Feminist Critiques of Capitalism in the Coalfields of Kentucky in the 1970s.” Gender & History 28, no. 1 (April 2016): 199–220. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-0424.12183 JSTOR

Wilkerson, Jessica. To Live Here, You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social Justice. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2018. https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/?id=p081406

Smith, Barbara Ellen. “The Role of Women in Appalachian Historiography.” Appalachian Journal 25, no. 4 (Summer 1998): 370–395. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40933860 Wiley Online Library

Brown, Karida. Gone Home: Race and Roots through Appalachia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018. https://uncpress.org/book/9781469647034/gone-home JSTOR

Bell, Shannon Elizabeth. Our Roots Run Deep as Ironweed: Appalachian Women and the Fight for Environmental Justice. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013. https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/?id=p079467 University of Illinois Press

Carter, Krystal B. “Women’s Grassroots Activism in Appalachia’s Environmental Justice Movements.” MA thesis, Appalachian State University, 2023. https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ The Library of Congress

Bagnoli, Chiara A. Women of Appalachia: Common Ground, Different Matriarch. Senior Independent Study thesis, The College of Wooster, 2022. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/10192 The Criterion Collection

Smith, Barbara Ellen. “The Council on Appalachian Women: Short Lived but Long Influence.” In The Council on Appalachian Women (ETSU master’s thesis context). https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2686 Digital Commons

Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (Global Nonviolent Action Database). “Harlan County, KY, Coal Miners Win Affiliation with UMWA Union, United States, 1973–1974.” Swarthmore College, April 24, 2013. https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/harlan-county-ky-coal-miners-win-affiliation-umwa-union-united-states-1973-1974 NVDatabase+1

“Timeline of Strikes in 1973.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Entry including the 1973–74 Brookside strike. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_strikes_in_1973 Wikipedia

Soodalter, Ron. “The Price of Coal, Part II: Bloody Harlan and the Coal War of the 1930s.” Kentucky Monthly, October 31, 2016. https://www.kentuckymonthly.com/culture/history/the-price-of-coal_1/ Oxford American

Arthur, Grace Elizabeth. “Documentary Noise: The Soundscape of Harlan County, U.S.A.” Southern Cultures 23, no. 1 (2017): 48–69. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/651705 Wikipedia

American Archive of Public Broadcasting. “Program about the Harlan County, USA Documentary Film.” Catalog record. http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-27-5m6251fx0z American Archive

Shannon Elizabeth Bell book review: Hao, Feng. “Our Roots Run Deep as Ironweed: Appalachian Women and the Fight for Environmental Justice, by Shannon Elizabeth Bell.” Contemporary Sociology 43, no. 4 (2014). https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/soc_facpub_sm/11/ Digital Commons

Council of the Southern Mountains / Appalachian Student Organizing Committee. Records referencing Brookside and Harlan County coal struggles, 1970s. Finding aid: Virginia Tech Special Collections, “Records of the Appalachian Student Organizing Committee, RG-31-14-10.” https://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=oai/VT/repositories_2_resources_3084.xml ead.lib.virginia.edu

https://doi.org/10.59350/21fbc-tfb61

Author Note: Writing about Lois Scott means returning to the roads and picket lines that still shape conversations in Harlan County. I hope this piece helps you see the Brookside women not just as figures on a screen, but as neighbors who transformed Appalachian history.