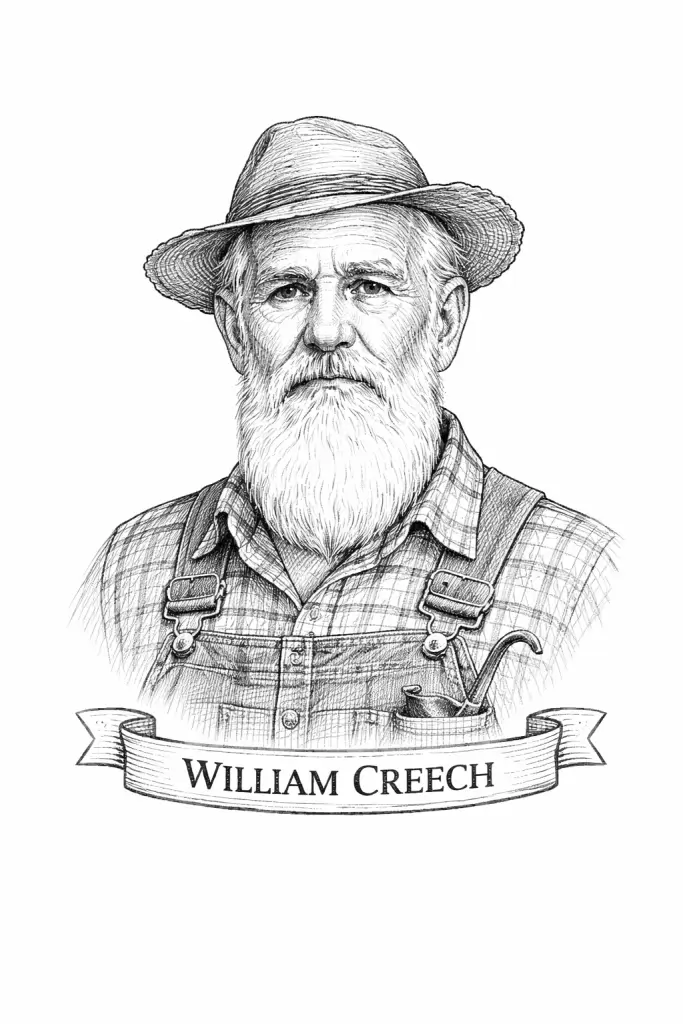

Appalachian Figures Series – The Story of William Creech of Harlan, Kentucky

William “Uncle William” Creech spent most of his life at the head of Greasy Creek in Harlan County, Kentucky, working land that he cleared with his own hands. Yet his name is remembered far beyond that valley because he turned much of that hard earned farm into the campus of Pine Mountain Settlement School and left a plainspoken statement of why he did it. His letters and autobiographical sketch, preserved today in the Pine Mountain Settlement School archives, let us hear the story in his own voice and follow it out through census schedules, war records, and land deeds.

A life told in his own words

The strongest single source for William Creech’s early life is the short autobiography he wrote around 1914 at the request of Pine Mountain co director Ethel de Long. In that “Short Sketch of My Life” he begins simply, “I was Born October 30 day 1845 on the Poor Fork of the Cumberland River in Harlan County Ky,” then goes on to name his parents, Joseph and Mary “Polly” Campbell Creech, as devout Regular Baptists who had little money for schooling but tried to raise their children “in obience to their savior.”

Pine Mountain’s genealogical notes on the Creech family confirm that William was born on Poor Fork, now the town of Cumberland, and identify him as the youngest of a large group of sons born to Joseph and Polly. The family had already been in North America for generations, with earlier Creech lines traceable through Virginia and North Carolina records before they appear in Harlan County by the mid nineteenth century.

When the Civil War broke out, William’s sketch explains that he had only “enough to read and write a little,” but at nineteen he left the farm and volunteered for Union service on December 30 1864. He was honorably discharged on April 12 1865 and returned home to help his father work the land. Federal compiled service records for Kentucky volunteers, together with later pension files, are where researchers can document that brief enlistment in detail.

On March 15 1866 he married Sally Dixon, daughter of William and Mary Gilliam Dixon, in Harlan County. The young couple first set up housekeeping in an old log house on his father’s land, but within a few years William concluded that the worn out farm could not support their growing family. That decision would push him over the ridgeline toward the land that later anchored Pine Mountain Settlement School.

Carving a farm at the head of Greasy

In his sketch William describes hearing about “wild land” for sale on the head of Greasy Creek. He bought two tracts totaling roughly seven hundred acres for one hundred forty dollars at six percent interest, payable not with savings but with his own labor. He and a brother carried food and tools on their backs thirteen miles into what he called the “back woods,” cut a campsite in a thicket of laurel and spruce, and began felling logs for a cabin.

The scene he paints is one of community as much as hardship. On the appointed day men from as far as twelve or fourteen miles away gathered with handspikes to haul logs and notch corners. In two days they raised and roofed a house, then William cut a door and window openings, split puncheon flooring from yellow poplar, and brought his young family in over a cold March road. For his wife, who had grown up in a more settled farming community, the loneliness of those early years at Till Hollow was nearly unbearable. William recalled that for weeks at a time she might not see a single traveler pass the door.

Piece by piece the Creeches turned the forest into a working farm. They cleared enough land for corn, wheat, rye, flax, and buckwheat. William raised sheep and tanned leather while Sally carded wool and flax, spun thread, and wove cloth. Children joined in as they grew, the boys helping with plowing and blacksmith work, the girls with weaving and house labor. Looking back, William estimated that the timber he had cut and burned for fence rails and brush clearing would have been worth tens of thousands of dollars in later markets, a reminder of how little mid nineteenth century mountaineers could foresee the cash value of their trees.

By the 1870s William had joined the Regular Baptist church, later serving as clerk after his father’s death. That role, along with his reputation as a hard working farmer, put him at the center of a growing settlement on the north side of Pine Mountain. Pine Mountain’s founder biography notes that over time he also operated a small store, served as something of an herbal doctor, and later helped secure postal service for the community, making his home place a local hub long before there was any talk of a school.

A farmer thinking about schools

Even as his farm grew, William’s own lack of schooling stayed with him. In his sketch he admits that he could only give his children the short three month “free schools” available several miles away. They learned to read and write, but he wanted more for them and for their neighbors’ children. That dissatisfaction, joined with his religious convictions, shaped the idea that the head of Greasy Creek ought to have its own school that would offer both “education and moralization.”

By the opening years of the twentieth century William had become a widely respected patriarch in the valley. As Pine Mountain’s institutional history points out, he advised younger farmers on crops, raised concerns about soil exhaustion and wasteful cutting of timber, and worried about the effect of liquor, disease, and violence in an isolated community with limited medical care. Later writers have emphasized that his thinking about a school was not just about book learning but about creating a place where better farming practices, public health work, and Christian but non sectarian values could all be taught together.

The campaign to bring a post office to Pine Mountain hints at how he thought about institutions. Popular accounts preserved in Ben Lucien Burman’s mid twentieth century book Children of Noah and Dave Tabler’s article “How the Post Office Came to Pine Mountain KY” recount how William encouraged his neighbors to send for mail order catalogs and, during the First World War, helped families write to soldiers so that postal officials would see enough traffic to justify a local office. Whatever embellishments crept into the storytelling, the core idea matches the man we see in archival sources: a mountain farmer who understood that institutions followed use and who was willing to do slow work to get them.

Letters that built a school

The decisive turn came in 1911 when itinerant Baptist preacher Rev. Lewis Lyttle visited the Creech home from Leatherwood Creek. In the course of conversation he told William and Sally about two women working at Hindman Settlement School in Knott County who were interested in starting another school on the north side of Pine Mountain. Those women were educator Katherine Pettit and Ethel de Long.

From that visit grew a dense paper trail. Pine Mountain Settlement School’s “PLANNING” files preserve letters from 1911 to 1913 in which William, other local families, Pettit, and de Long discuss possible sites, fundraising, and the mission of the proposed school. The correspondence shows Creech offering land on his farm, debating with the women over where to place buildings and roads, and insisting that the school remain open to children who could not pay full tuition. By 1913 deed work and site plans had come together and construction began in the narrow valley where Isaac’s Run and Shell Run form Greasy Creek.

Architectural histories like the SAH Archipedia entry and the Timber Framers Guild profile of Pine Mountain emphasize how important that topography was. Creech’s gift of land allowed Pettit, de Long, and architect Mary Rockwell Hook to design a campus that fit within the folds of the valley floor, combining log and stone buildings, terraced fields, and community spaces. Later National Park Service documentation and Kentucky Historical Society marker 2387 both note that Pine Mountain Settlement School opened in 1913 as a boarding school and settlement on land donated by William and Sally Creech.

“An old man’s hopes”

William’s most famous words about the school survive in a 1915 letter often called “An Old Man’s Hopes” or “Uncle William’s Reasons.” Addressed to friends and supporters of the young institution, it explains why he deeded land for the campus and what he wanted it to accomplish. One oft quoted line captures his reasoning: “I don’t look after wealth for them. I look after the prosperity of our nation.” He goes on to say that he wants mountain children to have good and evil laid before them so they can choose rightly and insists that the land be used “for school purposes as long as the Constitution of the United States stands.”

The Pine Mountain archives preserve that letter in manuscript form and also track its reuse in pamphlets like Uncle William’s Reasons, which circulated in the 1910s and 1920s as part of the school’s fundraising work. In 1945, when the school marked the one hundredth anniversary of the births of William and Sally, staff compiled another booklet titled One Man’s Cravin’ that wove his biography together with extracts from the “hopes” letter. Late twentieth century newsletters, notably a 1987 issue of Pine Mountain’s Notes, reprinted the full text again as a reminder of how closely the school’s identity remained tied to his words.

Illness, death, and memorials

By 1916 the school had begun observing an annual Founders’ Day celebration that honored William and Sally. For their fiftieth wedding anniversary staff and students staged a pageant, dressed Aunt Sal in her wedding dress, and presented the couple with a cake and fireworks. Two years later the community watched him decline. Letters from co director Ethel de Long (by then Ethel de Long Zande) and secretary Evelyn K. Wells describe his pain, the decision to take him to Norton Infirmary in Louisville, and the unsuccessful kidney operation that led to his death on May 18 1918.

His Kentucky death certificate, part of the state’s vital records series for 1911 onward, confirms the date and names Pine Mountain as his residence. The body was brought home for burial in the Creech Cemetery above the valley, where a headstone visible in modern photographs marks his grave and reinforces basic biographical details. Evelyn Wells’s narrative of the funeral captures the mix of grief and gratitude as neighbors, students, and staff gathered to honor the man whose land had made their school possible.

Commemorations continued long after 1918. Pine Mountain families and donors established a William Creech Memorial Fund; a stone drinking fountain was placed near the playground with a tablet honoring him; and the original Creech log house, complete with homemade furniture and hand woven textiles, was moved onto campus as “Aunt Sal’s Cabin,” a small museum of pioneer life. In 1991 the United States designated Pine Mountain Settlement School a National Historic Landmark, formally recognizing the national importance of the institution that had grown from his gift.

Finding William and Sally in the records

Because the Pine Mountain archives are unusually rich, William and Sally Creech’s lives are better documented than many Appalachian farming families of their era. Researchers can start with William’s own “Short Sketch of My Life” and the broader “William Creech Founder” page, which combine transcriptions of his writing, genealogical charts, and links to photograph galleries showing him as a young soldier, a middle aged farmer, and a white bearded elder surrounded by grandchildren. The “Creech Family Letters” guide pulls together correspondence from about 1911 through the 1930s involving William, Sally, their children, and school staff.

Federal census schedules for Harlan County locate the family at several stages. In 1850 and 1860 William appears as a child in Joseph and Polly Creech’s household along Poor Fork. By 1870 and 1880 he is listed as a farmer and head of household, and by 1900 the census places him among the landowning patriarchs in the Pine Mountain area. The 1910 enumeration still finds him in rural Harlan County, just before the school project begins to take documented shape. These entries, accessible through National Archives microfilm and online databases, provide ages, household members, and clues to kin networks around the head of Greasy.

Land records at the Harlan County clerk’s office, supplemented by compiled volumes of older deeds, trace his movement from Poor Fork to Greasy Creek and document the tracts later conveyed to Pine Mountain Settlement School. Civil War service can be verified through compiled service records for Kentucky Union volunteers, and a possible pension file for William or Sally in the National Archives may include affidavits from neighbors and family. William’s 1918 Kentucky death certificate and Sally’s 1925 certificate round out the vital records picture. Cemetery surveys and photographs from Creech Cemetery at Pine Mountain, including the headstone image circulated through Find A Grave and in Pine Mountain’s own galleries, supply physical confirmation of their burial place.

For historians, a group of scholarly works takes these primary materials and sets them in wider context. James S. Greene III’s dissertation Progressives in the Kentucky Mountains uses Pine Mountain’s records to explore how reformers like Pettit and de Long worked with local leaders such as William to create a hybrid of settlement house and rural boarding school. Mary Helen McQuillen’s thesis Pine Mountain: Community at the Crossroads of Appalachia and Elizabeth Jurgens’s study of settlement schools and adult education locate the school in the broader history of Appalachian modernization. Contemporary reference pieces like the SAH Archipedia entry on Pine Mountain and KET’s educational overview of settlement schools distill that scholarship for teachers and general readers.

Narrative and travel writers have kept William’s story in front of wider audiences. Ben Lucien Burman and Dave Tabler tell the post office story, Blue Ridge Country’s 2025 feature “In the Spirit of Pine Mountain” walks readers through the modern campus while quoting from his “Old Man’s Hopes,” and regional guidebooks such as Kentucky Off the Beaten Path and Craig Evan Royce’s Country Miles Are Longer than City Miles introduce “Uncle William and Aunt Sal” as emblematic figures of Pine Mountain and Harlan County.

Why William Creech still matters

Seen from one angle, William Creech was a typical nineteenth century mountain farmer. He cleared land, raised grain and livestock, served in the Civil War, and spent long years scraping a living from steep ground. What makes him stand out in the record is that he turned that life story into a conscious project for his community. While Progressive Era reformers brought outside training and resources to Pine Mountain, the idea that this particular valley should become a place of learning began with a local man who had wrestled with the limits of his own schooling and decided that his children and neighbors deserved more.

His letters and the school that followed bridge two worlds. On the one hand he belonged to the pioneer days of the Cumberlands, when families still ground meal on hand mills and slept on beds stuffed with leaves. On the other hand he anticipated a future in which rural Appalachian children would move easily between their home valleys and the wider nation. The fact that Pine Mountain Settlement School remains an active educational center, now focused on environmental education and cultural heritage, means that his “heart and craving” for a better life in the mountains still shapes new generations.

Sources & Further Reading

Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. “Publications – PMSS (Index of Notes, Pine Cone, and Related Publications).” Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/publications/ pinemountainsettlement.net

Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. “William Creech – A Short Sketch of My Life.” Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. Accessed December 28, 2025. https://pinemountainsettlement.net/biography-a-z/uncle-william-creech/william-creech-short-sketch-life/ pinemountainsettlement.net

Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. “William Creech Founder.” Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/biography-a-z/uncle-william-creech/ pinemountainsettlement.net

Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. “William Creech – The Death Of.” Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/biography-a-z/uncle-william-creech/william-creech-the-death-of/ pinemountainsettlement.net

Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. “Creech Family Letters Guide, 1911–1935.” Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=18997 pinemountainsettlement.net

Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. “PLANNING for Pine Mountain Settlement School.” Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=5542 pinemountainsettlement.net

Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. “Publications PMSS Ephemera Guide.” Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=66539 pinemountainsettlement.net

Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. “Bibliography: Pine Mountain Settlement School.” Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/bibliographies/bibliographies-guide/bibliography-pine-mountain-settlement-school/ pinemountainsettlement.net

Pine Mountain Settlement School. One Man’s Cravin’. Pine Mountain, KY: Pine Mountain Settlement School, 1945. Library record via NOBLE catalog:

https://montserrat.noblenet.org/GroupedWork/f9fdafb2-7277-28f4-4bf8-2164c7b9d46c-eng/Home montserrat.noblenet.org

Shinnick, E. D. “Department of Clippings and Paragraphs: ‘Uncle William’s Reasons.’” The Catholic Educational Review (1916).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23368616 JSTOR

“William Creech Sr.” Wikipedia. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Creech_Sr. Wikipedia

FamilySearch. “Kentucky, Deaths, 1911–1965.” Database with images. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://www.familysearch.org/

Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, Office of Vital Statistics. “Kentucky Death Certificates, 1911–Present.” Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://chfs.ky.gov/ Appalachianhistorian.org

Harlan County Clerk. “Harlan County Clerk’s Records Portal.” Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://harlan.countyclerk.us/ Appalachianhistorian.org

National Archives and Records Administration. “Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Kentucky (Record Group 94, Microfilm Series M397).” Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://catalog.archives.gov/

Find a Grave. “William Creech.” Creech Cemetery, Pine Mountain, Harlan County, Kentucky. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://www.findagrave.com/

Kentucky Historical Society. “Pine Mountain Settlement School (Historical Marker #2387).” ExploreKYHistory. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://explorekyhistory.ky.gov/ KET Education

National Park Service. “Pine Mountain Settlement School.” National Historic Landmark Nomination and Registration Form. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1991.

https://npgallery.nps.gov/ KET Education+1

Greene, James S., III. “Progressives in the Kentucky Mountains: The Formative Years of the Pine Mountain Settlement School 1913–1930.” PhD diss., Ohio State University, 1982.

https://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1249487592 Rave OhioLink

McQuillen, Marly Hazen. “Pine Mountain: Community at the Crossroads of Appalachia.” MA thesis, University of Memphis, 2014.

https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/949 Digital Commons

Jurgens, Eloise. “Southern Appalachian Settlement Schools as Early Initiators of Integrated Services.” Paper presented at the Mid-South Educational Research Association Annual Conference, November 6–8, 1996. ERIC document ED404097.

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED404097.pdf ERIC

Carbone, Cristina. “Kentucky.” In SAH Archipedia. Society of Architectural Historians. Accessed December 28, 2025.

https://sah-archipedia.org/essays/KY-01 SAH ARCHIPEDIA

Royce, Craig Evan. Country Miles Are Longer than City Miles. Pasadena, CA: Ward Ritchie Press, 1976. Google Books record:

https://books.google.com/books?id=-YRdUNPqHJ4C Google Books

“In the Spirit of Pine Mountain.” Blue Ridge Country, March 5, 2025.

https://blueridgecountry.com/newsstand/magazine/in-the-spirit-of-pine-mountain/ Blue Ridge Country

Author Note: As I look back across more than a century, I see William “Uncle William” Creech as the Harlan County farmer whose gift of land and stubborn, homespun vision made Pine Mountain Settlement School possible. His “old man’s hopes” for mountain children still feel startlingly clear to me today, and they continue to shape how I understand both the school and the wider story of education in Appalachia.